I'm ashamed to admit it, but the only reason I went to the kickoff meeting where I met my best friend and business partner was to score a free coffee mug. I wasn't expecting any Exiles to be there.

Now, normally I avoid corporate pep rallies, even when there's free loot to be had, but that time I had an ulterior motive. You see, you can tell how committed an aerospace company is to a project by the quality of the swag it gives the peons. So, while the business section obsessed about the outlook for international tourism and the UN's recognition of the Exiles, I simply clutched the stainless steel mug with the etched 7z7 logo surrounding an Exile shuttlecraft and saw two years of private school tuition for my daughters.

That was also where they debuted the ad. You know the one. "Around the world or around the stars, the Otherliner™ takes you there!" The animated plane taking off from Beijing, kids in a Midwest playground waving up at happy passengers. A media campaign for a piece of hardware that hadn't even been designed yet, let alone manufactured or flown.

You'd think we would've seen it as an omen.

"Thank you," Thermal cooed when the lights came up, assuming the applause was for him. His thumb absently scratched his scalp, a gesture universal to owners of poorly fitted hairpieces. "I'm glad everyone's as excited about this project as I am. Today marks a new chapter in our company's—no—in our planet's history. Now normally, I'd field questions myself . . ."

The auditorium filled with subvocal groans.

". . . but since this is a joint venture, we'll let our partner handle that. Allow me to introduce Chairman Smith, of the Exile Habitat Engineering and Maintenance Company."

Now that perked everyone up. Even I stopped recalculating my hourly contract rate and started paying attention. The Exiles might have been all over the media for the better part of a year, but none of us had ever seen one in the flesh.

The Chairman sidled up to the podium, switching from four footed stance to two-and-tail. At first glance, he looked exactly like the videos. Take a cave newt, one of the eyeless albinos from the documentaries with the narrator in a mining helmet, dye it slate gray and stretch it to eight feet long. Then stick a second pair of limbs just below the ribcage. For the head, put a porpoise's acoustic melon on top of the long, sinewy neck and a tentacled snout underneath, a sea anemone the size of a beer can. Add a three piece suit (shirt, pants, midlett–one garment for each pair of limbs) out of something that looks like navy blue wool.

"Thank you so much for those kind words," the translator strapped to the Chairman's chest said, converting his ultrasonic chirps to a bass monotone. "Before answering your questions, I would like to read a statement from my company to yours . . ."

As he droned, you could sense the entire auditorium lose focus. It appeared that the oratorical habits of middle managers crossed species.

"Ford," Marco whispered, elbowing my side. "He's wearing a rug, just like Thermal!"

I peered closer, realized the kid was right. Male Exiles have this small ruffle of down around the neck, perhaps as wide as a man's palm. In the Chairman's case, though, it appeared flamboyantly large and spanned several unlikely shades along its width.

"Maybe it doesn't look so bad on sonar." I shrugged. A lame joke, since Exiles actually see with a tiny eyespot just above the snout. But I got a snicker from my intern nevertheless.

"Are there any questions?" asked the Chairman when he'd finished reading his lines. Predictably, the audience was silent.

"Ask him," Marco whispered, nudging me, "what you said at lunch."

"No," I hissed back.

"C'mon. Chicken?"

"Me? You're the one who won't come out to the Soaring Club . . ."

"Ah," said the Chairman, swiveling his head towards me. "We have a question."

Damn. Too loud, I'd been caught like a rat in a trap. My embarrassment turned to irritation when I saw the two staff photographers covering the event nudge each other and begin to click away at me. I mean, I know the company's nuts for the whole "diversity" thing, but did they have to put an African American on the cover of the Employee Newsletter every time one stood up and asked a question?

"Well," I began, burying my annoyance. "I really have more of a concern than a question, Mr. Chairman. Er, Ford Gregory, Structures Group."

"Yes?" Perhaps it was just nervousness from talking to a bona fide extraterrestrial, but I swear I felt a beam of ultrasonic sonar boring into me. Several beams, in fact, when I saw about a half dozen Exiles seated in the front row turn their serpentine necks and look at me. An absurd notion, but no less so than feeling human eyes staring.

"Er, yeah. I'm just concerned about the risks of using Exile technology in our airplane."

"You mean safety? Because I can assure . . ."

"No, not that. Schedule and cost risk. For example, that video mentioned new technology that serves as the skin for your generation ship."

"Well, it's hardly a new technology," the Chairman replied. "Skin has protected our ship for centuries and its history goes back even farther. Very mature technology."

"A mature technology for keeping atmosphere separated from deep vacuum, perhaps," I said. "No one, though, not you, not us, has ever wrapped an aircraft with the stuff before. I just have doubts that something a hundred times lighter than the traditional materials can do the job."

"I understand your concerns," the Chairman said, "but the shearing stress of a micrometeor impact compared to anything an atmospheric craft might face . . ."

"It's not just about shear. There's other . . ."

"Thank you, Ford," Thermal interrupted. "But if we get into a debate here, we'll miss the refreshments at the back of the auditorium."

There was a chuckle from the crowd, followed by several hands going up. "Anyone else? Ah, Marilee! What questions does Systems Engineering have?"

In retrospect I couldn't blame Thermal for cutting off a debate that would have bored the rest of the auditorium to tears. Occupational hazard. Engineers argue the way fish swim.

Sure enough, though, the other questions were lightweight: How many Exiles were in the generation ship? (Four million) What did they think of Seattle? (Lovely, especially in the springtime) What was the most interesting thing they'd seen on Earth? (A tie between Mount Rushmore and Hollywood) How many planned to emigrate? (Very few. Most would stay in orbit and occasionally play tourist) Basically, a rehash of everything you could have gotten off the web.

The refreshments were good, though. After more speeches, Marco and I were critiquing the cookie tray when a voice surprised me from behind.

"I told the Chairman not to use those numbers."

"What?" I replied, concealing the stack of baked goods I'd been pocketing.

It was an Exile, a male from the front row. Unlike the Chairman, this fellow had a neatly trimmed crest of modest, although still healthy, dimensions. At first glance, it appeared all natural, too. Score one for those of us with receding hairlines who are still secure in our masculinity.

He stood about five feet in the two-and-tail posture, slightly shorter than the Chairman. Close up, I could see that the fine down that served the Exiles in lieu of fur wasn't solid gray, but was shaded in places. His midlett and trousers seemed slightly threadbare with a different cut than the Chairman's. The ancient suit I wear for job interviews and funerals suddenly leapt to mind.

"I told him not to use the one percent figure," the Exile continued, oblivious to my forced nonchalance and Marco's open gawking. "Valid for our application on the generation ship, but not yours. Ten times lighter, not a hundred, is more realistic."

"Really? I would have thought . . ." I paused, extended my hand. "My apologies, I'm Ford Gregory."

"Yes. 'Structures Group,' right? That would make you a materials engineer, too. Call me Thomas Patch."

There were handshakes all around when he extended the three fingered hand of one of his stubby midlimbs. His grip was firm through his glove/tabi sock garment, but in the back of my mind I remembered the old George Carlin bit about shaking hands with a guy missing some fingers.

"A materials engineer. So, um, what specifically do you do, Thomas?"

"Oh, I'm the chief engineer for the group that maintains the Skin enclosing our habitat."

"Er, ah, the skin that I said, er . . ."

Grace under pressure. Yup. That's me.

Thankfully, Thomas made a dismissive gesture, probably picked up in a briefing on human body language.

"Don't be embarrassed. You said nothing I wouldn't have if I didn't know the properties of Skin. I'd be skeptical, myself."

"Well," I said, "it sounds like a fascinating technology."

"Really? To us it's five centuries old, hardly glamorous. A career dead end, my parents warned me. Still, it's offered plenty of challenge over the years. In fact, we've improved Skin in a dozen ways during our journey. I doubt the inventors on Homebound would even recognize it."

"Well, I only wish I could learn more. But we're using carbon fiber for the 7z7 airframe."

"A good, conservative choice," Thomas agreed, nodding his faceless head. It must've been a very thorough briefing.

"Hey." Marco's unease was apparently abating. "Why will our Skin be ten times heavier than yours?"

"Photoelectric effect. Skin needs an electrical field to operate. Our version converts light from our Habitat's sun for power. Your version will need to include a power distribution network. Unless, of course, you always fly the planes westwards so they face the sun."

Wow. A giant newt telling a joke. Not a funny one, but still . . .

"Photoelectric? This stuff generates power like a solar cell? That's incredible!"

"Yes, it is." Thomas' translator injected a note of glee in his voice. "Skin really is beautiful stuff."

That should have ended it with Marco and me going back to our little cubicle to work with "good, conservative" carbon composites for the next three years. Instead, a voicemail from Thermal's assistant summoned me to his office to discuss the comments I'd made. On the way down the corridor, I dusted off my list of headhunters and contemplated a new job search.

When I entered Thermal's rosewood and brass lair, though, I was surprised by the absence of a security guard or Human Resources rep, the usual pallbearers at a firing. Instead of canning me, Thermal sat me down and turned on the charm. He said he liked that I "thought outside the box." I considered reminding him I'd actually been advocating thinking inside the Box, but I kept silent.

Then he blindsided me by offering a new job: leading the team that would work with Thomas to adapt Skin to the 7z7. I must've mumbled something vaguely affirmative because he leapt up and shook my hand.

I recovered from my daze long enough to seize on the ritual "If there's anything you need, just ask." It seemed only fair that Marco joined me. When I got back and told him we'd be working with new technology, that the fate of the project and perhaps the company would be resting on our shoulders, he thought it was a compliment.

I couldn't stop laughing for twenty minutes.

It turned out Thomas was absolutely right about Skin. It's beautiful stuff, a material scientist's wet dream. He hadn't even begun to scratch the surface, though.

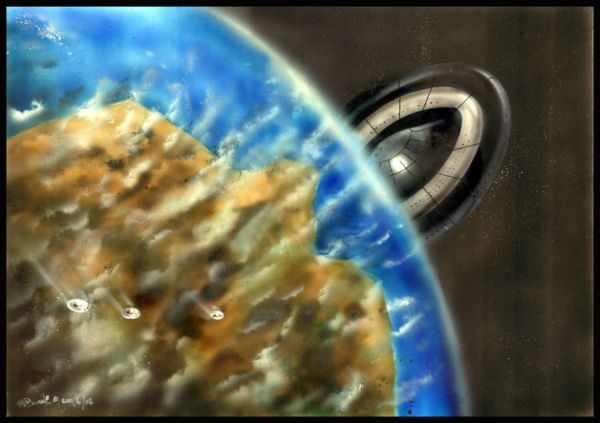

The Exile generation ship is a study in layers, a rigid, ring shaped space station spinning around an artificial sun. All this is inside a balloon of Skin 200 Km in diameter. The partially pressurized region outside the ring is used for recreation and zero gee agriculture, but also serves as a convenient buffer zone against junk that might collide with the craft.

Don't ask me about how they make the Reference Drive move the damn thing, sun and all. I never understood that loophole in Einstein's theories.

Skin is a nanotube mat, grown in vats rather than manufactured. Only 120 microns thick but with a tensile strength several hundred times greater than anything humanity ever developed. Embedded intelligent nodes dynamically change Skin's elasticity to deform in response to strain within milliseconds, a neural net with enough spare computing power to be a leasable commodity.

If there's stress on the Skin envelope, either from a micrometeor impact outside or an atmospheric gust inside, the strain is distributed over dozens of square kilometers. If there's a breach, Skin won't tear. Instead, it puckers until a repair crew responds to an automatic alarm.

This takes a lot of energy, hence the photoelectric properties Thomas mentioned. During most of the Exiles' three century journey, their artificial sun provided the power. With the habitat in Earth orbit, however, the light from Sol bathing the exterior generates several orders of magnitude more power than the Exiles need.

Which leads us back to the business section again.

The economists and pundits in the press speculated this was the real reason the Exiles had agreed to the 7z7 partnership. They'd announced a long term power project, beaming energy down to Earth. The 7z7 agreements would raise enough capital to build the dirtside receiver stations without human investors or partners, giving them an end to end power monopoly.

The fate of a company might have hinged on humans like Marco and me, but economic independence for all the Exiles rested on Thomas's and his cohorts' shoulders.

Figuratively, of course, because, you know . . . Four arms. No shoulders.

This (less the economic and anatomical speculation) was the essence of the lecture Thomas gave two weeks after my promotion. Thomas and his assistant, a female named Marjorie Currie (yes, that Currie. This was before she went into Exile politics, though), led the meeting.

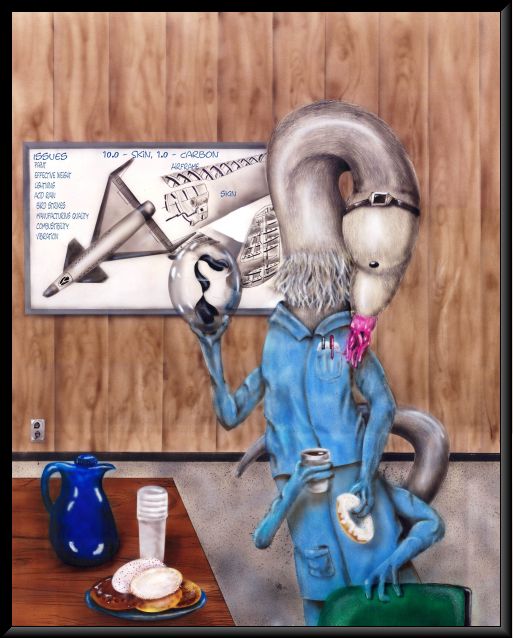

On the human side, the room was packed. There were only three permanent team members: myself, Marco, and Eleanor Compton, an underappreciated genius I'd poached from the landing gear group. During the eighteen month schedule, though, we'd be loaned aeronautical engineers, power distribution gurus, and other specialists for specific technical milestones. Forty people over the course of the entire program. At "Skin 101" they all showed up.

That's what happens when you spring for donuts.

"You can change the color, though, right?" asked Finn Radke, one of the aeronautic engineers, gesturing to a jar Thomas had passed around containing a sample of Skin. A ribbon of gossamer black as wide as an elastic bandage floated in clear fluid, ends spliced in a moebius strip. It threaded through the eyes of two sewing needles before flaring out again to full width. Thomas had programmed it to "swim", edges rippling as it zipped through the fluid, a hyperactive eel devouring its own tail. A watch battery attached to the needles provided power.

"I mean," Finn continued, "it isn't all black, right?"

Thomas nodded. "When we grow Skin, we can introduce impurities to change specific properties. There are three thousand known variants. We'll grow Skin with the livery of each airline already imprinted."

"So you can't paint it in the field?" That was Jay Tsai, one of the manufacturing guys.

"No."

"That's a big problem. Carriers change color schemes all the time, some to match holiday themes. And the leasing market, they move equipment between carriers like chess pieces. You have to be able to change livery in the field."

I nodded and walked to the whiteboard. Right next to the big "10.0 – Skin, 1.0 – Carbon" scoreboard I'd made, I wrote "Issues: Paint."

"So, this stuff uses power? That's gonna impact weight." This was Joyce Miller, from Systems Engineering.

"How so?" asked Marjorie's translator.

"Well, you're gonna burn fuel to get onboard power, which means more weight overall. I think 'effective weight' is a better term. Then there's wear and tear on the generators, but that's another issue."

And so "effective weight" appeared on the whiteboard.

"Forget power," grumbled Tom Hammond, flicking a piece of imaginary dirt from his Harley-Davison T-shirt (it was Casual Friday). "Lightning is your showstopper. You're changing the skin of an aircraft from a passive substance to an active device. The FAA DER will want proof it won't spasm and rip itself to pieces when it's zapped."

I nodded. Tom is not subtle. As a Designated Engineering Representative, the one who'd probably sign off on Skin for the FAA, he didn't have to be.

"Your DER," Tom continued, still using the third person, "will want a computer model of Skin's electrical as well as aeronautical characteristics. Be sure to simulate antennas, windows, and any other exterior features."

I gritted my teeth, sensing a cramp in my schedule.

And so it went, more and more issues: acid rain, bird strikes, manufacturing quality, combustibility, vibration. It was a close call, but they ran out of questions before I ran out of whiteboard.

"Sorry we're bringing up all these problems," said Jay.

"Don't apologize," answered Marjorie, who still had the stage from the manufacturing question. "After all, that's why you're here." Then, she touched her left hands together in a gesture I'd learned was an Exile grin. "Well, that and the donuts."

Chuckles all around, then a ragged chorus of "Thank you, Ford." Several balled up pieces of paper rained down on me. I returned the favor.

"Hey, Ford," chortled Jay, "maybe you can put this stuff on your hang glider!"

The price of fame. When you're the only black guy in the Soaring Club, the employee newsletter always uses your picture.

"If no one has any more questions, then . . ."

"I have one," said Tom. "Can you bring bagels next time?"

I'd love to say we fixed every problem handily, but I'm a lousy liar. With Joyce's fuel consumption numbers, I recalculated the "score," a weighting of manufactured cost, maintenance cost, and actual weight of Skin against carbon, from 10.0 to 6.5. Upper management gave us a pass on the initial development cost, but if that score ever went below the magic 1.0 mark the 7z7 would ditch Skin and I'd be out on the street.

Our first lightning analysis required beefing up the underlying conductor layer for better grounding (As Thomas said, "How much voltage? In an atmosphere!"). Then, a wind tunnel simulation showed more drag than expected, forcing Eleanor to develop a fiendishly costly polishing process. Acid rain showed a tendency to make Skin brittle and ready to flake under vibration, a bad thing for an aircraft to do. We added protective polymer coating, eliminating Eleanor's polishing process. She was glad to see it go, but the score dropped to 4.8.

It was death by a thousand cuts. Even if a problem didn't directly impact the effectiveness of Skin on the airplane, our solutions made manufacturing and maintenance ever more complex. The few things that didn't, such as the bird strike analysis (at least, for birds flying slower than meteors), still ate up time and budget. It wasn't enough that there was no problem: we had to prove there was no problem.

So, by the time we reached our first major milestone at Labor Day (on time and on budget, may I proudly say), I decided we needed a break.

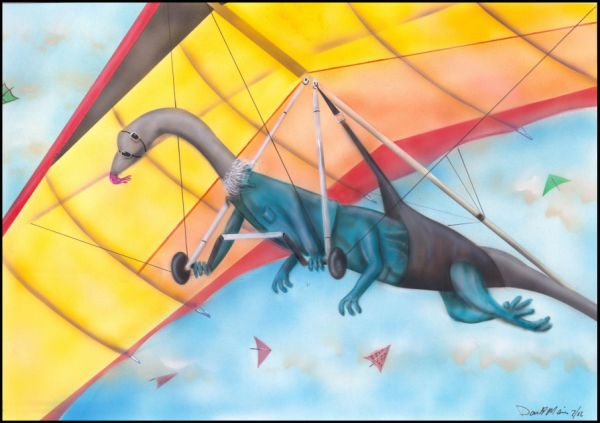

I got everyone together and we jumped off a cliff.

"Everyone" is perhaps an overstatement. Thirty people showed for the picnic at Hunter's Point, but only half took up the Soaring Club's offer of a free tandem flight. That was still enough to keep three gliders busy all afternoon.

"I'm ready," declared Thomas, marching up beside me. The other club members looked at the Exile, their expressions ranging from confusion to amusement to fear. Since I'd seen Thomas on the signup list earlier that week, though, I was ready.

"Okay," I answered, waving towards the scale. "Let's get started."

The relief of the other pilots that I was the one taking Thomas up was apparent. Several followed us to my rig, each trying to show how curious they weren't.

"The altitude won't be a problem for you, will it?" I asked as we walked. "I mean, with the pressure difference and all."

"I made a point of scheduling my booster shot for yesterday," Thomas replied. This was before the Exiles had developed treatments to allow their metabolisms to permanently adapt to Earth normal atmosphere. "The physician told me I should be able to handle anything a human can."

"Great." I nodded. Then, looking around, "Hey, where's Marjorie? I would have thought she'd want to see this."

"She went up to the Habitat late last night. Her mother had an emergency."

"Oh, no. Hope she's okay."

"It appears to be a false alarm, overwork and fatigue instead of heart trouble. Marjorie should be back next week."

"Wow. I'm surprised your company flew her back. I thought they only paid for one round trip per Earthside assignment."

"They didn't pay. Marjorie's parents have done quite well for themselves lately." He hesitated. "They're really good people, though. I went to school with her father."

For a moment, I could have sworn he was being defensive. A glitch in the translator's inflection or was he embarrassed about his friend's wealth? Before I could ask anything, though, Thomas produced a grubby nylon bag.

"I brought this." He dug out what looked like an oversized bicyclist's helmet, far too oval for a human skull. The frame was rigid white plastic while the front and top was a waxy, amber substance, presumably translucent to Exile sonar.

"We normally use these for zero gravity sports. Very sturdy. I've had this one for years."

Tammy Chen, the head of our safety committee, examined a nasty gouge along the helmet's edge before returning it. "I guess it's okay. As long as the fit's snug. You, um, did sign the waiver, right?"

"Of course," Thomas answered, placing the thing on his head and tying the complex triple strap with his left hands. With his right hands he attached knee and elbow pads and then strapped a thick monocular goggle over his eyespot. When he stepped on the scale in that bizarre helmet with the four armed T-shirt and baggy shorts, I nearly choked laughing, remembering a photo of my six year old self in oversized skateboarding gear.

Of course, I broke my arm about a half hour after that particular picture was taken.

"Let me get that, Mister Patch," my daughter said, helping Thomas step into the strap harness. Like every twelve-year-old, Gina has a mothering streak when it comes to adults out of their element. Several club members pitched in, each with their own theory of how to best secure a six limbed passenger in a harness designed for humans.

I checked my own bag harness where the rigging attached to the glider's keel. In tandem hang glider flight, the pilot and passenger are side by side, unlike in sky diving where the passenger hangs downwards in front. Thomas was half the weight, so he'd also be providing half the muscle power for takeoff.

I began my preflight lecture. "All right. First, we're going to sprint down this hill." I pointed to the slope before us to eliminate any confusion that I meant some other hill. "Once at speed, I'll shout and we jump into the harnesses. At the bottom we'll have maybe twenty feet altitude. I'll tilt towards the parking lot to catch its thermal. Let me do all the flying, okay? If you get nervous, just holler and I'll land as soon as possible. Questions?"

"Only one. My translator has never heard 'thermal' in that context."

"Pilot jargon. A rising mass of hot air, used for lift."

"Hmmm. 'A rising mass of hot air.'" Thomas pondered. "And just who bestowed the nickname 'Thermal' on the 7z7 vice president of engineering?"

There was a pause as I regained my bearings. "You do know that your life is in my hands."

"Of course," the translator replied.

I made a mental note that the Exile 'two left hands' gesture turns from a grin to a smirk when the fingers are intertwined.

After a last, somewhat dubious, check by Tammy we were off, hurtling down the gentle slope. Thomas's four legged gait surprised me with its strange rhythm. After a few steps, though, we caught each other's stride. I felt lift take the weight of the glider off the bar and I knew we were good. By the time I shouted "Now!" Thomas was upright on two legs, checking his pace so as not to out step me.

To me, that first instant of flight is always magical. Not in the spiritual sense, but instead in that I'm pulling some conjurer's trick by defying gravity. It's that "look Ma, no hands!" moment I love, whether I'm two feet from the ground or two thousand.

One glance at Thomas, however, confirmed that he was having a spiritual moment. His body was rigid, limbs tucked inwards and streamlined, rapt intensity. Thomas stretched his serpentine neck forward, crest ruffling as he washed his faceless head in the wind. All I could think of was how this scurrying, six limbed critter I'd worked beside for half a year had been transformed for an instant into something of noble posture, something straight out of a sculpture gallery. A grand creature.

And we were only twelve feet off the ground at the time.

As we began our upward spiral over the asphalt, I glanced again at my passenger. Thomas peered with his monocle as the gawking pedestrians below us receded and the contours of the terrain began to appear, no trace of panic or agoraphobia. I sighed relief into the rumbling silence. I'd been unsure how an alien raised inside a spaceship would react to this vista.

I began to enjoy myself, inhaling the crisp, frigid wind. I took a moment to gaze around, amazed again to see the Cascades in the distance, low hills and city spread nearby. A whole world laid before us, yet every detail visible.

Thomas wasn't the only one having a spiritual moment.

After fifteen minutes I shouted, "We're going to descend!"

Thomas's reply was lost in the wind. Then his interpreter increased its volume and he tried again.

"One moment," Thomas blared, the machine overcompensating. Then, in a timid tone at odds with the interpreter's blast, he finished, "May I try something?"

I felt him shift against my side, the slightest bit of drag yawing us gently to the left. I was about to compensate when I realized what was happening. I looked down to see his tail dipping downwards into the wind.

Thomas was trying to steer with his tail!

I let him continue, but his efforts had minimal effect. Three feet of skinny Exile tail isn't much against a hundred and fifty square feet of hang glider. Still, his experiment worked, if only in principle.

Back on the ground, Thomas was ecstatic. "Ford-that-was-incredible-I-have-never-felt-anything-like-that-we-must-take-anotherflightassoon—"

Then his translator locked up, emitting a screech that scattered a nearby flock of crows. When it reset, he'd regained a little composure. "Ford, you have to take me up again!"

"Well, it's supposed to be one ride a customer, but next week we're coming out . . ."

"Please! Can't I go again today? If you lend me your glider, I'm sure I could top our altitude!"

"Solo? After one flight?" I shook my head. I'd seen enthusiasm from a first timer before, but this was absurd.

Could an Exile have a death wish?

"Look, I'm glad you liked it, Thomas, but what's the big deal? Why the excitement?"

Thomas paused, fidgeting with his midlimbs.

"What do you know of my species' origin, Ford?"

"Er, you evolved from shoreline omnivores, right? Your ancestors swam in kelp forests past the surfline. Like Earth sea otters."

"Yes, our sonar and underwater vision are adapted for hunting in the oceans of Homebound. Only later did evolution bring us to shore to walk upright and use tools."

"What does that have to do with hang gliding?"

"My body is adapted to swim face down. Does the posture sound familiar?"

"Ah! When you were up there, you were belly down."

"Exactly. On Homebound, my people were accustomed to swimming freely over the ocean bottom. I never have, though. We have a whole body of poetic sagas that translate roughly as 'to fly in the sea.' All my life I have lived in a confined environment, never even knowing a horizon. Now, though . . ." He paused, four hands clenching and unclenching, as if trying to grasp the words from the air. "Even with this confining goggle to correct my distance vision, the experience was . . . heavenly."

I nodded and put a hand on my friend's back. For once, we didn't need the translator to understand each other.

The Labor Day outing worked, at least for morale. Productivity picked up and grumbling (including mine) about overtime died down. We were still fighting the tyranny of that score on my white board, which now read a disturbing 2.7, but at least the troops were enthusiastic about charging into the fray.

Three months later, Thermal called an emergency meeting.

"It can't be good," Thomas brooded, pouring a cup of coffee. The break room was empty, overcast sky gray against the windows. "Emergency meetings are never good."

"Thermal is probably just gloating about leaving for the powersat project," I said.

"It's about our jobs," he whispered, his free hands fidgeting nervously. "You know that the Exile Council rescinded the lifetime employment guarantees."

"Yes, I heard." I sighed and took the offered coffee pot. I winced as Thomas's upper arms scooped tablespoons of sugar into the mug in his lower hand. "You told me, Thomas. About five times since yesterday."

"Of course. Still, Thermal's leaving makes me nervous. What's the English phrase? 'Rats leaving a leaking ship.'"

" 'Sinking ship.' Sinking is worse than leaking."

"Hmmmph," he mumbled, sticking his snout into his mug. I cringed as he slurped the contaminated brew and we exited the break room and started down the hall. "Obviously, whoever invented English never lived in a space habitat."

"Remind me never to go yachting with you, okay?"

A moment's pause that Thomas always used to broach new subjects.

"I still like 'Yellow Bird'," he proclaimed, referring to the da Vinci-esque hang glider coming together in my garage. It was the first designed for a four armed, long tailed, Exile pilot. Building it was a blast, but the name was a sore point. "'Yellow Bird' adds grandeur, dignity. You saw the videos . . ."

"Yes," I interrupted, recalling the clips of the long extinct species soaring over Homebound, a canary yellow condor with biplane wings eating roadkill. "Look, it's your rig, so you have final say. But don't you think it's bad luck?"

"Why would 'Yellow Bird' be bad luck?"

"You honestly don't think that naming a dangerous, prototype aircraft after a carrion eater is a bad idea?"

"No. Why should I?"

I shook my head. Apparently, you can not only take the Exile out of the food chain but you can also take the food chain (or at least the fear of mortality) out of the Exile.

"Thank you for coming, gentlemen. Grab a seat." I felt my stomach lurch. If Thermal had showed up early instead of his usual ten minutes late, this really was serious. I checked my watch to ensure we were on time, but it didn't calm me any.

"Now," Thermal began, adjusting his hairpiece absently, "we need to be on the same page here. I'm not pointing fingers or blaming anyone . . ."

Beside me Eleanor let out a quiet whimper of terror.

". . . but we have to figure out how to get the Skin project back on track. Frankly, you guys aren't the only team in trouble." Everyone nodded. The Propulsion Group's antics had caused a site wide evacuation and left building sixty-six smelling permanently of burnt milk. "Still, I'm worried. The entire airplane is at risk." He pounded his fist on the table. "We need solutions, people!"

A nice speech. Also, the last civil words he spoke that morning. Frankly, if berating us could have helped the situation, Hurricane Thermal would have fixed the entire project before lunch.

"And what about these integration tests?" he snapped an hour into the blame-storming session. "Wind tunnels ain't cheap, you know! And you want to pump lightning through one? That's what computer simulations are for!"

"Sir," I answered, "we can't be sure our models of complex aerodynamic behavior for Skin are accurate. I built the whole schedule to accelerate this testing . . ."

"But the other tests came up great. This stuff's been used for centuries! Why not just cut . . ."

"Sir," interrupted Thomas, politely but firmly butting into Thermal's tirade. "I have kept the Chairman abreast of our progress and he agrees with our testing regime. Until nine months ago, my people had never even exposed Skin to Earth's atmosphere. While we're making incredible progress here, when would you rather find any problems? In three months on a wind tunnel mockup or next year when the FAA starts throwing lightning at a full sized fuselage?"

Thermal scowled, but apparently was at a loss how to glower at a creature without a face. He paused a moment, as the spreadsheet deep inside his toupeed cranium weighed the risks.

"Fine. You've got your test, Ford. Next up, though, we need to talk about reducing overtime expenses . . ."

Score: 1.22

We won that battle, but the fifteen weeks leading to Lightning Discharge Testing were a nightmare. I don't know how many hours we worked because we stopped recording overtime. Suffice to say that styrofoam noodle dinners and sleeping bags under desks lose a lot of their charm for a man of my advanced years.

It wasn't just the hours, though. Marco and Marjorie discovered a flaw in our manufacturing process. When we scaled up to mass production, our yield of uncontaminated Skin would fall, dropping the score to 1.22, only somewhat preferable to carbon composites. When the big day rolled around, I just wanted the entire ordeal to be over.

"Telemetry ready," Eleanor's tinny voice called over the video link. Then, with an audible smirk, "How's the weather back home?"

Computer modeling had made wind tunnels as common as Ford Model Ts, so we had been forced to rent time at another facility. Frankly, we'd been lucky to find one that could get the scale wind speed and voltage we needed without going overseas.

"It's raining here," I grunted, pausing to swill some more coffee. "As if you didn't know."

"Rain? They have legends about water falling from the sky here in Arizona. Silly superstitions."

I chuckled, glancing around the conference room at the team. Thomas was in the corner, sharing data with Marjorie on an obsidian tablet unreadable without ultrasonic sonar. Tom Hammond and Finn Radke were off to the side, Tom's motorcycle boots propped up on the walnut conference table. There were deep bags under Marco's eyes, but he gave a "thumbs up," confident the test was a formality, that our models had been perfect.

"You promised we could take the whole weekend off when this works," Marcos said. "Right?"

"A promise is a promise," I agreed.

"Actually," Marjorie said, turning away from Thomas, "I might want to use that time off a little later."

"Sure."

"And," she said, hesitating as she looked back at Thomas and then at me, "I need to ask you two a favor when that happens. A big favor."

"The tunnel's ready," interrupted a stranger's voice over the link. "Releasing smoke now."

The image on the wall showed the top of a 7z7 wing twenty centimeters long, threads of yellow smoke curving gracefully over the slate gray Skin surface. A red display in the corner tracked the speed of the air pumped through the stainless steel tunnel, slowly creeping upwards.

"Airspeed 200 scale knots," called the stranger's voice. "Preparing for test step 1a. Discharging in ten, nine, eight . . ."

"Jeez, Tushar," growled Eleanor to the tunnel manager, "we're paying for the tunnel by the minute! Stop padding your paycheck, okay?"

The audio link died under a sea of static, the video link staying rock steady while a bright blue arc danced across the wing. The part of me that had loved Frankenstein movies as a kid was disappointed that the lightning source was out of frame. Oh, well. They wouldn't be using a Tesla coil anyway.

Two seconds later, it was over. A hundred mild lightning strikes, each faster than the eye could see. We'd increase the charge in later runs, but for now the conference room erupted in cheers at the image of the unscathed wing and undisturbed smoke threads. I sighed relief as Thomas patted me on the shoulder.

"Ah, guys . . ." Eleanor called, breaking into our celebration. "We have a problem."

"What?" I asked. "It looks just . . ."

"Check the underside."

I fumbled the remote and heard Tom Hammond's boots thump to the floor at the same moment my jaw did. On either side of the engine cowling the neat laminar threads of smoke had shattered into chaotic lumps of rippling turbulence, like forest fires quivering with caffeine jitters. While we watched, the patches shrank, retreating to the engine pylon before disappearing entirely.

"I'm rewinding to T plus 100 milliseconds," said Eleanor. I shook my head in disbelief as the freeze frame showed nearly half the wing on either side of the engine lost in a cloud of turbulence. Jay spoke first.

"Jesus. Half the wing . . ."

"Half the lift," corrected Tom. "We loose half the freakin' lift when hit by lightning!"

"And it lasts," interrupted Eleanor, "two point five seconds before recovering to eighty percent lift for five seconds. I don't know if that'll stay there when we scale up or not."

"If it'll get even worse," I moaned, as if it would matter. This was more than enough to crash a plane on takeoff. "What the devil is causing it?"

"The engine," answered Thomas. He stepped forward, pointing to ripples in the cloud's edge on the image. "There's oscillation, see? The skin twitches slightly when charged, as if reacting to an impact, but our grounding dissipates it in just a few milliseconds so it's lost in the turbulence of the lightning strike itself. As expected. But underneath, the engine cowling isn't covered with Skin."

"The shock wave reflects back," I said, "and when it reaches the Skin—"

"Which reacts to the change in pressure and bounces it back again. And so forth. Oscillation. Technically it's not turbulence, but a wave of energy dancing back and forth along the face of the wing."

"Unless some of that energy is facing downwards to hold the plane in the air it's pretty irrelevant, isn't it?"

Thomas fell silent, then gave a very human four-armed shrug.

Two hours later, Eleanor was on an early flight home. We halted testing when a mid-sized strike lost 90% lift for half a minute. Thomas made a quick calculation that showed tripling the thickness of the grounding layer would dampen the oscillations and make Skin safe from anything the FAA could hurl. I followed with a calculation of what the new weight would do to Skin's score.

We all left the conference room in silence.

With a sigh, I hammered my status E-mail to Thermal and went outside for the first time in recent memory. I savored the scent of a March drizzle, tasting raindrops on my tongue. After a stinging hot shower at the company gym, I shaved and packed up my gym bag. Sure enough, I returned to find a voicemail waiting.

Before I even opened the door to Thermal's office, I knew he wouldn't be alone this time.

"Those bastards," hissed Marco the next morning.

"I'll land on my feet. Hand me another box, willya?"

"Those worthless, two faced bastards."

I accepted the box and rummaged through my desk, trying to figure out how I'd accrued so many plastic forks.

"You should sue," Marco said. "I mean, they have to give you notice, right?"

"He's a contract worker, Marco," answered Eleanor. "There's nothing he can do."

"The labor board, then."

"What part of 'contract worker' didn't you understand?" Eleanor growled. "Basically, anything shy of selling his organs without his consent is fair game."

"You can't leave, Ford."

"Really?" I chuckled. "Perhaps if you told Thermal . . ."

Just then Thomas and Marjorie walked up two-and-tail, Thomas carrying a cardboard box in his toplimbs.

"Dear Lord . . ." whispered Marco.

"Those bastards," agreed Eleanor.

"Thomas?" I asked. No answer.

"He . . ." said Marjorie, clenching all four hands into angry fists. I had an image of a 1-2-3-4 rabbit punch combination. "He just finished a teleconference with the Chairman."

"Thomas," I repeated, taking my friend by the top bicep. "I'm so sorry. When are you going back? To the Habitat?"

"I'm not," he whispered.

"What?"

"The Chairman," Marjorie began, wringing an amazing amount of contempt from her translator, "says the Exile Habitat Engineering and Maintenance Company reserves its shuttle seats for employees only."

"Those bas . . ." Marco began, only to be interrupted by a fuming Eleanor.

"Let me get this straight, Thomas: You warned your management from the outset that Skin might not be suitable for our application. You spent a year working yourself sick, keeping them abreast of every technical issue. You did no worse than a half dozen other teams that failed. And then, when everything falls apart, they fire you and leave you down here stranded?"

"Yes," Thomas answered.

"Man, you guys are more like humans than I ever thought."

"Don't they owe Thomas a trip back?" asked Marco.

"Under our old laws, definitely," said Marjorie. "During our journey, we were a sealed society. The only way to keep things stable was to provide lifetime employment in exchange for lifetime loyalty. As we integrate into Earth's economy, though, there is a movement to drop rules that are inconsistent with free market profit."

I nodded. Market reform is a bitch.

"I tried to convince Thomas to go before the Grievance Council and demand a trip home, but he refuses."

"What good would it do?" Thomas asked. "Every job in the Habitat is allocated, and some are even being eliminated under the new rules. Besides, I've only done one thing my entire life. What else can I do?"

Traditionally, this would've been where I patted Thomas on the back and said "Buck up, old chum!" Unfortunately, I was pretty emotionally drained myself at that point.

"Ford," said Marjorie, breaking the long silence, "do you remember that favor I mentioned during the wind tunnel testing? Well, I know this is a poor time, but I have to ask you and Thomas for help before you leave."

"What do you need?" I asked, eager to change the subject from unemployment.

"My parents are visiting in three weeks. They saw Thomas flying Yellow Bird on one of the entertainment channels in the Habitat."

I nodded. For the first time the employee newsletter hadn't featured me in its annual story about the Soaring Club. How the wire services had picked up Thomas's photo, I'll never know.

"My mother wants to try it. She wants to fly."

"No problem," I answered. "We're going out with the Soaring Club next month."

"That won't do," she replied. "They're only here for that weekend."

"We can arrange something," answered Thomas. "Perhaps it'll keep our minds off our problems. Right, Ford?"

"Sure. Nothing quite like . . ."

"One second," interrupted Eleanor, turning to Marjorie. "Did you say your folks were coming down on the shuttlecraft for the weekend?"

"Yes. It's all the time they can spare."

"Marjorie, I would have to mortgage my house to get a shuttle ticket."

"Well, my parents have done well for themselves lately."

There. That defensive tone again.

"Marjorie," I asked, "just what do your parents do?"

"Oh, they're our Economists. It was really a very dry and academic field . . ."

"Until the Habitat reached Earth," I finished. The Exile Economists. During their journey, only two Exile academics had bothered to study the esoteric field of exchanging goods and services for money, a worthless concept while traveling between the stars. I'd read that they'd designed the entire Exile business strategy, a multibillion dollar juggernaut of which the 7z7 represented a minute fraction.

"Of course, you really have to credit Mom with negotiating that half percent commission. You'd be amazed at how it adds up."

I shook my head. Couldn't they see the solution hovering right in front of their, er, snouts?

"Marjorie," I asked. "Can't your folks just loan Thomas the price of a shuttle tick . . ."

Both Exiles suddenly threw all four palms rigid and outwards as if to push me away. Thomas' box crashed to the floor. It took two seconds of dead silence for me to realize what had insulted them.

"Um, forget I mentioned borrowing money."

The pair relaxed, assuming their original postures. Thomas lifted his box from the floor with his lower limbs. He poked through the contents as Marjorie cast around for something to do to cover her own awkwardness.

"Look . . ." Marjorie began, hands grasping nervously, "I know you mean well, Ford. My parents are, well, progressive about finances. I doubt they'd think less of Thomas for beg . . . I mean, borrowing the funds. Still, most of our people in the Habitat wouldn't understand."

"We are still adjusting to the concept of personal wealth, Ford," Thomas explained. "You will have to excuse our taboos about unearned money."

I nodded and pretended to understand. In a sealed, regulated economy, who would have any needs so strong that they'd go into debt? Gambling addicts? Criminals? It implied the existence of all sorts of Exile vices I'd never considered before.

"So," Marco asked Marjorie, trying to change the subject. "Where are your folks going to stay?"

"Well, they said they'd be fine using the futon at my apartment. I think they deserve something more."

"What if . . . " Thomas pondered, clearly forming some plan in his mind. "What if you went away for the weekend? A tour of Washington wine country. Bed and breakfasts. I'm sure Ford knows dozens of places."

"Huh?" I asked. "I guess I do."

"Certainly." Thomas nodded. "Glide in the morning, wine tasting in the afternoon. A personal tour of the countryside while staying in some beautiful places. Much better than the futon. Of course, my partner and I would have to charge a fee."

I stared at him. "Partner?"

"You don't mind putting engineering consulting on hold for a while, do you?"

I felt a grin spread across my face. "Get paid to fly? I think I can manage that."

"Well," said Marjorie, still weighing Thomas's proposal. "That all sounds nice. Dad told me he had tried a wine while he and Mother were looking at investments in Europe. Something called a 'Riesling,' I believe."

"He's looking for investment opportunities, you say?" Thomas asked. It's incredible that someone without a face can cast me a meaningful look.

"If your folks will let Thomas and me take them out for the weekend," I promised, "I'll buy them a case of Riesling."

"Hmmm," Marjorie said. "I'll call and see if that's what they want to do."

The Rieslings never panned out, but fortunately for Patch and Benjamin Glider Tours, LLC, it was a terrific year for Washington state Chardonnays.