"Governor-General's dead."

I glanced up from the disassembled comm-comp I'd been trying to Frankenstein together. The G-G was Core. Unkillable. But Mox didn't look like he was kidding.

"How?"

Mox's expression was more intense than during orgasm. "Field Control says the west face of the Capitol Massif collapsed in a quake. Took most of the palace with it."

A few million tons of rock and masonry trumped even invulnerable immortality. "Shit. Yeah, that might wipe out Core. Wonder what Mad Dog Bay looks like now."

"Scary stuff, Vega."

I rubbed my forehead. "Field got any instructions?"

"Hold position, maintain current activity, refuse all orders not from direct chain of command."

Think, dammit. What was important? Besides the possibility of a House coup, that is—with my brother in the thick of the plotting, no doubt. Murder most foul, if it were true.

"Why should anyone care what we do?" I asked myself as much as Mox.

For the love of inertia, we were planetologists. What we cared about was Hutchinson's World, and most of all, the mystery of the Big Ice. The unusual degree of variation in density and gravity readings. Its challenging thermal characteristics. The stray biologicals deep down where they shouldn't be.

Mostly those freaky biologicals, truth be told.

We were neither armed nor dangerous. Our station had a tranq gun, for large, warm-blooded emergencies, but there wasn't much we could do out here on the ass end of nowhere about a succession crisis back in Hainan Landing. There wasn't anything interesting about us—except me.

Mox gave me a look I couldn't interpret. "You tell me."

Core ruled.

It was the way of things, had been for centuries. Core was jealous of their history, told one set of lies to schoolkids, another to those who thought they needed to know more. I'd never believed that they were the result of progressive genengineering in the twenty-first century. Smart money in biology circles was split—very quietly split over home brew in the lab on Saturday night—between a benevolent alien invasion and something ancient and military gone terribly wrong.

Some would say terribly right.

Core didn't rule badly.

They took what they wanted, what they needed, but on planets like our own lovely little Hutchinson's World, Core was spread so thin as not to matter. Economy, law, society, it all lurched on in an ordinary way for ordinary people. I had a job, one that I mostly liked, that kept me out of trouble. So far, Core hadn't done so badly by the human race, driving us to 378 colony worlds the last time I saw a number.

Core believed in nothing if not survival. I wondered how someone had managed to drop a palace and half a mountain on the Governor-General without his noticing the plot in progress.

"You still finding those protein traces in the deep samples?" Mox asked. He was back to biology, using one of our assay stations, distracting himself from disaster with local genetics. My instrument package on the number one probe was down in the Big Ice around the four-hundred-meter layer, digesting its way through Hutchinson's specialized climatological history.

I didn't need to look at the readouts. "Yup." It was slightly distressing. There shouldn't be genetic material hanging around in detectable quantities that far below the surface. The cold-foxes and white-bugs and everything else that lived on the Big Ice lived on the Big Ice.

It was also distressing not knowing what was happening back in Hainan Landing—but not as much to me as it obviously was to Mox. He kept glancing at the comm station, his features tense. Mox and I lived and worked in a shack high up on Mount Spivey, almost two thousand meters above the Big Ice's cloud tops.

Far enough away from politics, I had thought.

He gave me a long stare. "Anything else I need to know?"

I looked away. "Nope."

The Big Ice was a bowl, a remnant impact crater from a planetoid strike so vast that it was difficult to understand how Hutchinson's crust had held together under the collision. Which arguably it hadn't—the Crazydance Range, more or less antipodal to the Big Ice, was one of the most chaotic crustal formations on any human-habitable world, with peaks over twenty thousand meters above the datum plane.

The bowl of the Big Ice was over a thousand kilometers across, thousands of meters deep, and filled with ice—by some estimates over 10 million cubic kilometers. A significant percentage of the planet's freshwater supply was locked up here. The Big Ice had its own weather, a perpetual rotating blizzard driven by warm air flowing over the southern arc of the encircling range that rose to form the ragged rim of the bowl. The storm rarely managed to spill back out, capping an ecosystem sufficiently extreme by the standards of the rest of the planet to keep a bevy of theorists busy trying to figure out who or what had ridden in on top of the original strike to seed the variant life-forms.

From our vantage point, it was like looking down on the frozen eye of a god.

Our instruments were in a cluster of military-grade shacks just above the high point of the ice-tides, deep inside that storm. We made the trip down there as rarely as possible, of course, though making that trip is something every adventure junkie ought to do once in their life. That long, cold, frightening journey into the depths was the main reason why we were on the Ice instead of lurking in some remote telemetry lab back in Hainan Landing. Every now and then, someone had to climb down and kick the equipment.

And deep beneath the surface of the Big Ice, below that cap of raging storm, was genetic material that had no business being there.

I started awake to find my sometime-lover staring at me. "Planck on a half shell, Mox! You scared the shit out of me." I stifled a yawn, my mouth still filled with sleep.

His expression was the attempt at unreadable I had begun to fear. "Field Control called back in."

"Looking for us, or just delivering another bulletin?"

"Us. Asked for someone named Alicia Hokusai McMurty Vega, cadet of the House of Powys. Took me a minute to figure they meant you."

I gazed at him a moment, rubbing my short-cropped hair and trying to wake up the rest of the way. Had I just been dreaming that he'd figured out who I was?

It didn't matter now. My cover was shot, no matter who had dredged up my full name. "What did they want?"

"Seems your presence is desired in Hainan Landing." He leaned forward. "Are you going to tell me who you are, Vega?"

I wasn't sure if I could. The identity he wanted from me now was one I had rejected long ago.

Maybe I could save this friendship. "When did we first meet?"

"Over six years ago," Mox replied promptly. He'd been thinking about it.

My gut turned over with something that felt like regret. "And we've been out here more than five months alone, right? I'm still Vega Hokusai, just like I've been all these years. Still a planetologist."

He locked his hands behind his back—I had the impression that he was making an effort not to touch me. Which had its own novelty; our relationship had never been characterized by impulsive, passionate embraces.

"And a cadet of the House of Powys," he pressed out.

I should have known I couldn't escape it. "We all come from somewhere. It's not who I am now."

"It's who they're asking for, back in the capital."

"Screw them." I was surprised to find I meant it.

And screw my brother, too. This would be his doing.

A cadet of House Powys. To graduate, to leave House training, someone had to die. A real death, irrevocable, not the strange half-life they could and did place us in for decades on end. One cadet had to kill another. Secretly. Plots shifted and revolved for years.

That was how House cadets discussed things. One death at a time.

When next Mox approached me with That Look, I was deep in protein analysis. Hutchinson's native gene structure was pretty well understood, though we still couldn't reverse-engineer an organism just by scanning like we could with terrestrial genes. Didn't have centuries of experience and databases, for one. It was still a small miracle how stable the underlying gene model was across planetary ecosystems: kept the panspermists going.

Either way, I didn't know what I had yet, but it was interesting—no matches in our planetary databases. Not even close.

"Vega?" His voice was low and tense.

"Uh-huh?"

"Can't we talk about this House stuff?"

I flipped off the virteo-visualizer and turned to face him. "Not much to say."

He looked up from the tranq gun he was polishing. Which didn't need the maintenance. "What are you doing out here?"

I wanted to laugh. "Mox, it's the Big Ice. I'm studying it, same as you. You think I'm out here plotting revolution? Against what? The cold-foxes?"

He shifted on his feet and stopped polishing the gun. "Got another call. I'm supposed to arrest you."

Ah, Core asserting itself against whatever House effort my brother Henri was running in light of the G-G's death. Or Henri calling me in through channels, over clear?

Either way, it didn't look good for me.

I couldn't take Mox's hand now—he felt betrayed, and he would think it calculating. Which maybe it was.

I shook my head. "I may have been raised by wolves, but I really am a planetologist. Six years you've known me, you've seen enough damn papers and reports from me. Am I faking this?" I taped the virteo-visualizer.

"No . . . you're good at archaeogenetics, and you've got a decent handle on climate as well."

"And anyway, when would I have had time to run a revolution? Against Core, for the love of Inertia."

"I don't know, Vega."

He really was considering it. Perhaps our relationship had been more convenience than anything else, but still . . . this was Mox. I hadn't killed anyone since I left House, but my training—my programming—wouldn't allow me to let him do me in either.

I swallowed. "Mox, put down the gun."

He set the tranq pistol on the workbench, and I let out a breath I hadn't known I'd been holding.

I favored him with a smile accompanied by a high dose of pheromones. If I'd had a choice, I wouldn't have resorted to the manipulation, but autonomous survival routines were kicking in. "Thanks."

There was no answering smile on his face. "Now tell me why they want you in Hainan Landing."

"I truly don't know. But I'm not going back if I have any say in the matter." I'd made my peace with Core, thought I'd seen the last of my House progenitors. I wanted no more of Henri and Powys House, no more of Core and plots and power. The Big Ice and the mysteries of Hutchinson's were my life now.

What if they threw a revolution and nobody came?

Mox glanced at the tranq pistol. "You're House. Doesn't that mean you're like another version of Core?"

I shrugged. "We're not immortal, if that's what you mean. You've known me six years. Noticed the gray hairs?"

His gaze shifted from the pistol back to my eyes. "A superwoman." It was almost a whisper.

Unfortunately, he was very nearly right, but I didn't want to go there. "Seen me fly lately?" I asked dryly.

Then number one's telemetry alarms started going off. We both spun to workstations, bringing up virteo-visualizers to an array of instrumentation.

Something was eating the number one probe. Four hundred meters below the Big Ice.

A text window popped up in my virt environment as I tried to make sense of the bizarre thermal imaging. So low-tech.

Coming for you. Be ready. Henri.

Situation alarms flared on the station monitor at the deep edge of the virteo.

Core made enemies. They controlled all interstellar travel, most of the planetary economies, the heavy weapons, and they couldn't be killed. Usually.

But for the revolutionary on a busy schedule, even cliffs can be defeated in time, by wind and rain, by frost, by tree roots, by high explosives.

The Houses were rain on the cliff face that was Core. Long-term projects established by very patient people, well hidden—some on the fringes of society, some within the busiest bourses in human space.

Certain Houses, Powys for one, raised their children in crèches as seeds to be planted, investments in the future. I was one seed, left to grow in comfort as a planetologist. My brother Henri was another, raised as a revolutionary, just to see what would happen to him.

Seeds are expendable. Houses are built to last.

Whatever was savaging our number one Big Ice probe, all we could tell about it was that it wasn't biological. Thinking about that gave me a bad case of the fantods.

Satellite warfare was going on overhead, judging from the dropouts in the comm grid and exoatmospheric energy pinging our detectors. Planetary Survey, ever thrifty, had put neutrino and boson arrays on top of our shack for correlative data collection in this conveniently remote location—and those arrays were shrieking bloody murder.

I figured I had an hour tops before Henri got here, with a couple House boys or girls in case I got fussy. Henri was a Political. I was . . . something else. Something Henri needed?

What was a good House soldier to do?

I turned to Mox. "I'm going down to the Big Ice and try to rescue our probe."

He froze. "Four hundred meters deep? Planck's ghost, Vega, you can't get that far under the ice! Even if you did, you'd never make it back."

I didn't know what to say, so I didn't say anything.

We were only sometime-lovers, but still I could see the exact moment he realized. "You don't intend to come back."

I shook my head. "My cover's blown. I may as well try to rescue the probe on my way out."

Mox looked away, no longer willing to meet my eyes. "So what can I expect?"

"House for sure. Probably Core, too, following after."

"Shit."

"Play stupid. Don't mention Powys House, don't say anything about anything. Tell them I went down on a repair mission."

"And if they come after you?"

The decision made, I was already up and pulling gear out of the locker. "The Big Ice is dangerous. They have to fly through that frozen hurricane, handle the surface conditions, and find my happy ass. Accidents happen."

"Vega . . ."

I looked up. Mox had that intense look again, the one I had only seen in bed up till now, but he wiped it off his face before I could get up the courage to respond. House gave its seeds all kinds of powers, but bonus emotional strength wasn't one of them.

"Yeah?" I finally choked out.

"Good luck."

"You, too, Mox."

"I hope you make it."

"Thanks. So do I."

Moments later, I was outside. Day's last golden glare faded behind the western peaks. Colored lights glowed in the sky, orbital combat (coming for me?) mirrored by hundred-kilometer-wide spirals of lightning in the permanent storm of the Big Ice, glowering dark gray fifteen hundred meters below. I could smell ionization even up on Mount Spivey. Thirty-five hundred meters above the datum plane, the air gets thin, and the weather can be pretty shitty by any standards other than those of the Big Ice.

It was glorious.

Our base shack was on a wide ledge, maybe sixty meters deep and four hundred long. Nothing grew on the bare cliff except lichens and us. Power cells and some other low-access equipment had been sunk in holes driven into the rock, but otherwise the little camp spread across the ledge like an old junkyard, anchored against wind and weather. I glanced at the landing pad, but there was nothing I could do about anyone who might arrive and threaten Mox.

On the other side of the landing pad was the headworks of the tramway running down to our equipment shacks Ice-side. It was a skeletal cage on a series of cables, quite a ride on the descent. Unfortunately, the ascent required hours of painful winching, unless you wanted to climb the ladder that had been hacked and bolted into place by the original convict work crew.

I didn't have time for the tram today. I snapped out the buckyfiber wings I'd brought with me months ago and stashed against a day such as this.

Big, black, far less delicate than they looked, they could have been taken from a bat the size of a horse. There were neurochannels in my scapulae that coupled to the control blocks in the wings, wired through diamond-reinforced bone sockets meant to accept the mounting pintles. Once I fitted them on, they would be part of my body.

My gear safely stowed in a harness across my chest and waist, I opened my fatigues to bare the skin of my back. The wings, tugging at the wind already, slid on like a welcome pair of extra hands. The cold wind on my skin was a tonic, a welcome shock, electricity for batteries I'd long neglected.

I stared down into the vast hole that was the Big Ice, the crackling lightning of the storm beckoning me. I spread my wings and leapt from the icy ledge into the open spaces of the air.

One theory about the Big Ice was that it was an artificial construct. The thermal characteristics required to drive such a vast and active sea of ice had proven extremely difficult to model. Planetary energy and thermal budgets are notoriously challenging to characterize accurately one of the greatest problem sets in computational philosophy, but the Big Ice set new standards.

So fine, said the fringe. Maybe it was a directed impact all those megayears ago. Maybe something's still down there, some giant thermal reactor from a Type II or Type III civilization come out of the galactic core on an errand that ended up badly here on Hutchinson's World.

Yeah, and cold-foxes might pick up paintbrushes and render the Mona Lisa.

But there were those nagging questions . . . all a person really had to do was stand on the rim wall somewhere and look down. Then they would understand that the universe has impenetrable secrets.

Flight is the ultimate high. The wind slid across my skin with lover's hands, and the muscles in my chest stretched as my back pulled taut. I could see the crosscurrents, the play of gravity and lift and pressure combining in the endless sea of air to make the sky road. A hurricane bound solid and slow in crackling ice, but no less deadly, or frightening, than its cloud-borne cousins over the open sea.

Below me, the lidless, frosty eye of the world beckoned.

I spilled air, leaning into a broad, circling descent that gave me a good view of the blizzard's topography. Even by the light of the early evening, the core of the storm was foggy, a cataract in the eye, but the winds there would be very low. The lightning on the spiraling arms of the storm bespoke the violence of the night.

Fine—I would ride the hard winds. I continued with my wide curves, circling a few kilometers away from the cliff face that hosted our shack and Mox. I hoped he would be okay, play it easy and slow, a bit stupid. Neither Core nor House would care anything for him.

And hopefully he would forgive me someday for keeping things from him.

With that thought, I expelled the last of the air from my lungs and accelerated my descent.

A few hundred meters above the clouds, my sky-surfing was interrupted by a coruscating bolt of violet lightning.

From above the storm.

"Inertia," I hissed as I snap-rolled into the crackling ionization trail from the shot, a near miss from an energy lance. With a quick scan of the sky above me, I saw a pair of black smears shooting by. Interceptors, from Hainan Landing, running on low-viz. Somebody wasn't waiting for me to come in.

Gravity and damnation: I didn't have anything that would knock down one of those puppies. I slipped into another series of rolls. None of their targeting systems would lock on me—not enough metal or EM, and I was moving too slow for their offensive envelope—so it was straight-line shots the old-fashioned way, with eyeball, Mark I, and a finger on the red button.

The human eye I could fool, and then some.

They circled over the storm and made another pass toward me. I kept spinning and rolling, bouncing around like a rivet in a centrifuge. Think like a pilot, Vega. I spilled air and dropped straight down just before both lances erupted. The beams crossed above me, crackling loud enough to be heard over the roar of the storm below.

It took some hard pulling to grab air out of my tumble. I regained control just above the top of the storm, a close, gray landscape of thousands of voids and valleys, glowing in the light of the rising moon. It was eerily quiet, just above the roil of the clouds. The background roar I felt more in my bones than heard with my ears, like a color washing the world; the detail noises were gone—all the little crackles and hisses and birdcalls that fill a normal night. The only other sound was the periodic body-numbing sizzle of lightning bolts circling between cloud masses within the storm.

I had no electronics except the silicon stuffed inside my head. If I got hit hard enough to fry that, there wasn't going to be much future for me anyway. But those clowns on my trail had a lot more to lose from Mother Nature's light show than I did. So I cut a wide spiral, feinting and looping as I went, trying to draw them down closer to the clouds. They came after me, in long circles nearly as slow as their airspeed would allow, the two interceptors snapping off shots where they could.

It was a game of cat and bird. When would they fire? When should I weave instead of bob? I'd already surrendered almost all my altitude advantage. I didn't want to drop into the storm winds until I was close to my target, not if I could help it. My greatest problem was that I was muscle-powered. I couldn't keep this up nearly as long as my attackers could.

Then one of them got smart, goosed up a few hundred meters for a diving shot.

Gotcha. I rolled slow to give him a sweet target.

My clothes caught fire from the proximity of the energy lance's bolt. I twisted away, relying on the flames to take care of themselves in a moment, praying for my knowledge of the storm to pan out.

It did. Multiple terawatts of lightning clawed upward out of the clouds, completing the circuit opened by the energy lance's ionization trail. My bogey took enough juice to fry his low-viz shields and probably shut down every soft system he had. Regardless of its ground state, there's only so much energy an airframe can handle. Number one clown might not be toast, but he had too much jam sticking to him to be chasing me anymore.

Number two got smart and dropped below me, skimming in and out of the cloud tops. I guess he figured on there not being much more air traffic here tonight. I watched him circle, angling for an upward shot. Angling to draw the lightning to me.

Time for the clouds, Vega.

I folded my buckyfiber and dropped away from violent death, a bullet on the wing.

The storm was hell. Two-hundred-kilometer winds. Hail bigger than grapes. Sparks crackling off my wingtips, off my fingers, off my toes.

I loved it.

I had no idea where number two interceptor was, but he couldn't have any better idea where I was, so I figured that made us even. Neither House nor Core was going to find me down here. And to hell with the Governor-Generalship.

I was still a hundred kilometers or more from the probe, my real reason for being here. In the storm, I could steer—a little—and ride the winds—a lot. But it was like being inside a giant fist.

The training of my childhood came back to me, hard years in dark caves and abroad on moonless nights, initiating trickle mode. I could breathe as little as once every ten to twelve minutes when my blood was ramped up. The tensile strength of my skin rose past that of steel, shattering the ice balls when they hit me.

There's a beauty to everything in these worlds. A spray of blood on a bulkhead can be more delicate, ornate, than the finest hamph-ivory fan from Vlach. A shattered bone in the forest tells a history of the death of a deer, the future of patient beetles, and reflects the afternoon sun bright as any pearl. Take the symmetry in the worn knurl on an oxygen valve, the machined regularity of its manufacture compromised by the scars of life until the metal is a little sculpture of a tired heaven for sinning souls.

But a storm . . . oh, a storm.

Clouds tower, airy palaces for elemental forces. During the day, the colors deepen into a bruise upon the sky, and now, at night, they create the only color there is in the dark. The air reeks of electricity and water. Thunder rumbles with a sound so big I feel it in my bones. The blue flashes amidst the rainy dark could call spirits from the deep of the Big Ice to dance on the freezing winds.

I flew through that beauty, fleeing my pursuer, racing toward whatever was consuming our number one probe.

The Houses aren't places, any more than Core is. They're more like ideas with money and weapons. Maybe political parties.

Powys House, as constituted on Hutchinson's World, was spread through several wings of the Governor-General's Palace of late lament. I had grown up occasionally visible as a page in the G-G's service. Between surgeries, training time, and long, dark hours in the caves of Capitol Massif.

Core is everywhere and nowhere. The Houses are nowhere and everywhere. Some believe there is no difference between Core and House, others that worlds separate us.

I spent my childhood falling, flying, being made both more and less than human.

I spent my childhood training for a day such as this.

Down below the cloud deck, I traded the storm's beauty for the storm's punishment. Here there was nothing but flying fog, freezing rain, ice, and wind—wind everywhere. It was brutally cold, frigid enough to stress even my enhanced thermal-management capabilities.

Screw you, Core. If that other bastard behind me made it to the Big Ice in one piece, I would give him a cold grave.

Then a gust hit me, a crosswind powerful enough to flip me with a crack of my wing spar and drive me down on to the Big Ice headfirst. I barely had time to get my arms up before I plowed through a crusted snow dune into a frigid, scraping hell.

"Damn," I mumbled through a mouthful of ice. That wasn't supposed to happen, not with these wings. The neurochannel control blocks screamed agony where the connections had ripped free on impact. I shut them down and began the wiggling, painful process of extracting myself. After a couple of minutes, I pulled free to see a pair of ice-foxes watching me.

"No food today," I said cheerfully over the howling wind, for all the good it would do me. Ice-foxes are long-bodied, scaled scavengers—and deaf. They eat mostly white-bugs, lichen, and each other; but at forty kilos per, they could be troublesome.

Something changed in the tone of the wind, and I looked up in time to see the second interceptor roar by overhead, shaking on the wings of the storm. The ice-foxes vanished into the snow.

The Big Ice is shaped more like a desert than an ocean of ice, with dunes, banks, and troughs formed in response to the permanent storm. There are some density variations, relating mostly to aeration of the ice formations, but also trace minerals and pressure factors. The surface even has features mimicking normal geology—outcroppings, cliffs, crevasses. The difference is that geology sticks around for a while. The Big Ice . . . well, it has tectonics, but at human speeds rather than planetary.

Which for us mostly meant there'd never been much point in making or keeping maps. Every day was an adventure, down in the pit of the storm.

I was within a few kilometers of my instrument package's tunnels. The entrances would be filled with snow, possibly blocked by falls, but as long as at least one was open, I was in business.

I wasn't here only to avoid Core or whoever was after me—I hadn't lied to Mox when I told him I was a planetologist. The mystery of the Big Ice fascinated me, belonged to me, was mine to decipher and share, so much more important to me than Powys House and politics and Core. My brother would never understand.

And then I was sliding and struggling for footing against the wind, vehemently cursing what fascinated me.

The tunnel was a surprise when I found it. The number one probe had trundled across the Big Ice to this point, though its tracks had long been erased by wind and storm. As its entry point, it had chosen a solid cliff facing leeward, the closest thing on that particular stretch of the Big Ice to a permanent feature. The ice had preserved a tunnel like a black maw in the pale darkness.

I experienced a sudden shiver that had nothing to do with the temperature. At least I'd be out of the wind.

To access the tunnel, I had to get down on my hands and knees. It was almost like slithering, making me wish House had given me some genetic material from ice-worms. The tunnel was shaped in the slightly off-center ovoid cross section of the number one probe's body, the ice had melted, then injected into the walls to refreeze in denser spikes that served to reinforce the tunnel. Half-crawling, I had some clearance for my back, though not much. Were I to lie flat, I would barely have enough room to operate a handheld. Otherwise, it was a coffin of ice.

Hopefully I could prove deadlier than whatever might actually be inside the Big Ice.

To see, I had to use low-wave bioflare. It hurt my planetologist's soul, but I didn't want to be surprised by anything before finding the probe.

It was damned cold in the tunnels. My thermal management was keeping up, mostly due to the blessed lack of wind beyond a slight updraft from below, probably stimulated by some version of the Bernoulli effect at the tunnel mouth.

And if I had been merely human, the cold and the dark probably would have slain me with despair and hypothermia.

Stray voltage and a faint trace of machine oil led me to the probe. I approached cautiously, not sure what awaited me, what had sabotaged the probe.

In all the history of Core and House and humanity as a whole, no one had ever found an alien machine. There were worlds that showed distinct signs of having been mined, or worked for transportation routes and widened harbors. But never so much as a rivet or a scrap of metal to be found: no machines, no artifacts.

And so we scoured the odd places for odd genetic signatures. Though as the centuries of Core raveled onward, it had become increasingly clear that the oddest genes were in our own cells.

Finally I found the number one probe, quiescent but not dead, and no evidence of what had savaged it.

The probe was vaguely potato-shaped, a meter-and-a-half wide by a meter tall in cross section and three meters long, with a rough surface studded with the bypass injectors that had created the tunnel. From the rear, it looked normal. No sign of the attacker. Just me and the probe, four hundred meters below the Big Ice.

Had our telemetry been spoofed? The trick was as old as Tesla's ghost, but the probe was stopped. That was more than spoofed telemetry.

I shut down, slipping into passive recon mode. Black. Dampened my EM signatures, turned off my thermal management. Nothing but me and my ears on all their glorious frequencies.

The Big Ice groaned and cracked, settling into the rotation of the planet, the stresses of the crustal formations around and beneath it, breathing, a frigid monster half the size of a continent.

But there was something beyond that.

The gentle slide of crystals on crystals as the walls of the tunnel sublimated.

The distant echo of the storm.

A very faint click as something metallic sought thermal equilibrium with its surroundings.

And out of that near silence, a voice.

"Good-bye, Alicia." My brother Henri.

As fast as I was, he was faster. I was buried in tons of the Big Ice almost before I could even finish the thought: sororicide.

"House cadets are typically killed in their twelfth or thirteenth year of life. Appropriate measures are taken to preserve the brain stem and other structures critical to identity maintenance and retention of their extensive training. They are then left in a state of terminality until new training is called for. This process is considered critical to the development of their character, and since the dead know no flow of time, their thanatic interruption is not experienced by them as such. Some House cadets have waited centuries to be revived."

House: A Secret History in Fiction, (author unknown), quoted by Fyram Palatine in A Study of Banned Texts and Their Consequences, Fremont Press, Langhorne-Clemens IIa.

I found myself, reduced in cognitive ability, packed in loose snow.

Which meant I wasn't embedded in ice.

I have cavitation-fusion reactors within the buckyplastic honeycomb of my long bones. This means, given any meaningful thermal gradient at all, I will have energy. Even for exceedingly small values of thermal gradient. Such as being adjacent to a three-meter mass of plastic and metal, deep below an ice cap.

And given energy, the bodies of House, like the bodies of Core, will seek life. Repeatedly.

But if I was no longer buried in the ice, how long had I been here? My internal clock refused to answer.

Inertia.

I hadn't reached this state overnight. A cold stole over me that had nothing to do with the Big Ice. I could have been down here for months. Years even.

Then I realized I could hear the wind, close, which meant I was just below the surface. I had some muscle strength, so I pushed toward the noise. And if I heard noise, I had ears.

Above the rushing sound of the wind came some kind of long, drawn-out wail, not natural. With the part of my brain which was re-forming, I identified it as a siren.

Warning? Or call?

With my internal clock nonfunctional, I had no idea how long it took me to emerge from the snow, but eventually I did, body changing with my progress. There I found I could see.

I was at the base of a shallow hill—the cliff where the probe had tunneled? Worn by time and wind? How long had I been beneath the Big Ice?

The siren wailed once again above the white expanses, and I followed it, climbing frozen wastelands.

With hands that weren't human.

I stopped, staring at the thing that had once been a palm with fingers. Now it was a claw, the skin a blue-fired tracery of webbing no human genome had ever produced. I had regrown myself from the stray organics down beneath the Big Ice.

The mysterious archaeogenes were within me.

And then another sound, a shot, followed by pain and a giant roar that wrenched itself out of my gut.

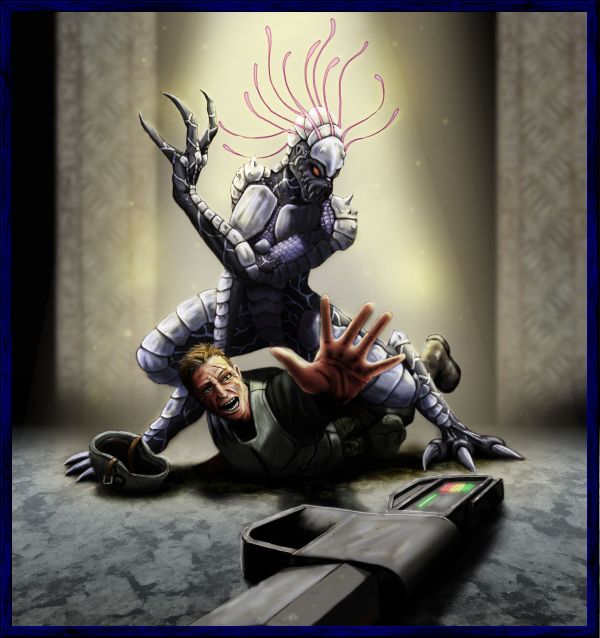

Mox stood above me, tranq gun poised, his expression bordering on terror.

I felt a surge, a burn of some strange emotion, retaliation, vengeance, but I fought it back, allowing the tranquilizers to work, staring at Mox, willing him to understand.

How could I make him realize that the monster in front of him was me?

I came to in a room in our shack, my hands and feet tied with rudimentary restraints I knew wouldn't hold. Mox sat across from me, tranq gun across his lap, still looking scared and dazed.

Some primal impulse wanted to break my bonds and him, too, for trying to restrain me; but the part of me that had once been human was able to retain the upper hand.

I tried to speak, but all that emerged was something resembling a roar. Mox started up, gun trained on me.

I tried again. This time at least it was recognizable as speech.

"Planck on a half shell, Mox. Put down the gun." It was my quietest voice, but it reverberated off the walls of the little shack.

Mox winced and dropped the tranq gun. "Vega?"

I nodded; the less I spoke, the better.

"What happened to you?"

I shrugged. "The archaeogenes."

"But how?"

"House."

House was hard to kill. I had metabolized ice.

Mox nodded. He'd seen the data on the stray biologicals, too, and he thought I was a superwoman. He accepted it. He believed me.

The beast in me quieted.

"Now what?" he asked.

"Take me to Hainan Landing."

It had been over a year since my disappearance, and my brother Henri was now G-G. Core.

Unkillable?

"I did my research after you disappeared," Mox said. "Killing siblings is regarded as necessary to advancement among your kind."

"I was no competition," I roared. I wished there were something I could do about my beastly voice.

Mox winced, shaking his head. "Even if you assumed you'd taken yourself out of the running, he didn't assume that."

I don't know how I thought I could ever get away from House politics.

Since Mox had originally been ordered to bring me in before I went to find the probe, we decided that was what he would do—arrest me and take me to Henri. That would be the simplest way to get me to a place where I could confront my brother. There was a surge of that emotion again, the one I associated with the beast, a cross between anger and a powerful sense of ritual, like I imagined formal vengeance might once have felt.

Of course, the risk was that he would kill me on sight, but I was willing to take it. Besides, knowing Henri, he'd be curious to find out how I survived.

He would want to see me.

The transporter was a tight fit—it was made for two humans, and I had become very much bulkier.

As we flew over Hainan Landing, I inspected the changes. Capitol Massif was a mountain of rubble spilling into what was left of Mad Dog Bay. The city itself didn't look much different, its white low-rises spread like ancient pyramids among an emerald jungle topped with birds and flowers, bucolic existence beneath the gentle, guiding hand of Core. Flatboats and pontoon villages still graced the waterfront—surely new since Capitol Massif had collapsed. That must have been quite a tsunami.

But not caused by an earthquake, I was certain of that now. Until I saw the city, it had still seemed possible that Henri had capitalized on a natural occurrence to further his ambitions.

Only too much of Hainan Landing was still standing.

Interceptors filed into formation with our transporter and accompanied us to the landing pad of what I presumed was the new palace, on the other side of Mad Dog Bay from the remnants of Capitol Massif and in a geologically stable location. A squad of heavy infantry was waiting when we stepped out of the vehicle, me with my clawed hands bound behind my back for verisimilitude. They formed up around us and led us through hallways even more convoluted than those I remembered from childhood.

Perhaps House really could become Core.

Then the hallways gave way to a huge audience chamber, paneled in mirrors to make it seem even bigger, and I was confronted by image upon image of what I had become—huge, ungainly, webbed, blue. Inhuman. Ugly as sin and more dangerous. How had Mox been able to converse with me as Vega? Look into my eyes and see the woman who had once been his lover? The sight of me scared even me.

But then there was my brother, standing at the end of the large room, hands locked behind his back, his stance mirroring my own bound wrists. Except that he still had the deliberately chiseled features of House: a look determined to provoke admiration, a look calculated to command. While I was something Other.

Beauty and the Beast.

Henri looked from Mox to me and back again. "This is supposed to be my sister?" he asked, one finely sculpted eyebrow raised for effect.

"Henri!" I roared before Mox had a chance to answer. My voice shattered the mirrors lining the hall and made my brother finally look at me seriously.

Henri shook his head. "This does not look like Alicia to me. Your humor is in poor taste."

The sense of formal vengeance surged, and I growled, causing everyone, including Mox, to step back.

Mox caught himself first. "Just talk to her."

"This could not have once been a human being."

"I think she reconstructed herself out of the archaeogenes in the Big Ice."

"But what is there in this—thing—to make you think it's her?"

"Planck on a half shell!" I bellowed, tired of being ignored. "Henri! Why?" It was all I could do to keep from breaking my bonds and tearing my ostensible brother to shreds.

Henri winced with everyone else in the hall at the sound of my voice, but now he was looking at me rather than Mox, accepting my transformation, recognizing me by my words if not my voice or my appearance. The calculating smile of House began to curl his lips.

No, not House. Core.

"Politics," Henri said, as if that explained everything. Which, of course, in terms of Core it did. "You were supposed to stay dead down there."

"Well, I'm back now," I said. More glass exploded. Was my voice growing bigger, or only my anger?

Henri actually laughed. "Yes, but bound."

This time I couldn't control the surge of emotion, and I snapped the buckyplastic bonds as if they were twine. Half a dozen guards stormed me, but I reached out one long, clawed arm and slapped them away, surprised at my own power. One guard began to rise, his weapon trained on me, but I broke his back and left him howling on the marble floor. I would have broken more, but then I saw the way Mox was looking at me, his expression even more horrified than the first time he had seen me.

"Halt!" Henri cried out, uselessly; by this time, no one was moving except the screaming soldier.

He approached me and stopped, facing me at arm's length. "As you look to be quite difficult to kill, sister, I have a proposal to make."

I could slay him before anyone shot me, I knew it—arm's length was not nearly distance enough for his safety. The being I had become calculated the speed and distance and moves without even thinking, and I kept this form's inherent need for formal vengeance in check only through the greatest effort.

And the awareness in my peripheral vision that three of the soldiers still standing had moved closer to Mox, weapons ready.

I had not moved my head, but I saw somehow that Henri was cognizant of my assessment of the situation, knowing in the same way that I knew exactly how to break his neck.

"Proposal?" I echoed.

Henri smiled, sure of himself—Core. "I could use a creature like you at my side, you know. You would make a fearsome bodyguard. And you are no threat to my ambitions now . . . like this."

Like this. A monster, no longer House. What I had always wanted—but not like this.

"I might kill you," I bellowed.

He shook his head. "No. Because you, too, are Core. Sister."

"I'm not Core."

His smile grew even wider. "What then?"

Yes, what? A killing machine, obviously. And I could kill my brother—who, after all, had killed me first—kill him, and free Hutchinson's World of Core.

Two aides hurried in and loaded the wounded guard onto a stretcher. The man's screams faded to whimpers as they hauled him away.

In the moment of departure, I could scent everyone. The wounded man's blood and pain and bodily fluids, Henri's brittle confidence, and fear everywhere. They were all scared—Mox, the guards, even Henri. Everyone was scared of the beast I had become.

What was underneath the Big Ice? What was so dreadful, so powerful, it had to be buried in such a huge grave?

Me. Something like me.

Did it have a conscience? Did I have a conscience?

I turned that thought over in my head. I was big, powerful, House-trained, angry—and back from the dead. I could challenge Henri here and now on his own ground. Somewhere inside me, that sense of formal vengeance stirred again. Some actions were fitting.

I gave that thought long consideration. Slow as the Big Ice, I turned it around and around. Some actions were fitting, but some actions were not.

Perhaps Core was not such a bad thing after all. And, as Henri had pointed out, if House Powys had become Core on this planet, then I, too, was Core—albeit monstrous Core now. But Core or not, I couldn't stay here, where I would likely kill anyone who crossed me. I could be better than whatever the Big Ice's archaeogenes had made me, better than what House had made me.

I could be better than my brother. I could be more than the sum of my biology. I did not have to accept his offer.

"I will not be your bodyguard."

My brother's smile disappeared. "Then I will have to kill you again, you know."

That he might. But what choice did I have? And how successful would he be this time? I looked at Mox, whose fear of me seemed to have fled. He held my gaze a long moment, and I imagined I saw some flicker of our old companionship.

Mox understood. And for his sake, I had to go.

I glanced once more at Henri. "I am not Core, and I never will be. Dead or alive, that will not change." I turned, expecting energy lances in my back.

Henri surprised me. None came.

I walked through the shards of shattered mirrors and down the long corridors and out of the New Palace, walked down to Mad Dog Bay and into it, walked beneath the waters and across the face of the land for days until I got home to the Big Ice.

Broad, deep, a world within a world. My place now. My family, my House. My Core. Perhaps if I dug deep enough, I could find a new brother.

[Jay Lake is the author of several novels.

See more of Ruth Nestvold's work at: www.ruthnestvold.com.