—Tacitus, HISTORIES, I, 4:

The soldier stands alone. In the time when he must either succeed or encounter failure that will follow him beyond his grave, he has only a little time and only two considerations—his mission, and what strength he has within himself by which he may accomplish it. Whether he commands a million other men or only the weapon in his own hand, the soldier in the moment of decision is of all men most alone. Whatever of harmony he has achieved in his adjustment to the world as he knows it is the source of his strength. If he has adjusted himself only to chaos, it is in this time that he will dissolve and lose himself in its nothingness.

—Joseph Maxwell Cameron,

The Anatomy of Military Merit

The most important fact of the first half of the Twentieth Century is that the United States and England both speak English. The most important fact of the second half will be that the dominant race in both the United States and the Soviet Union is white.

—Herman Kahn, 1960

CoDominium: The first attempts by the United States to forge a CoDominium alliance were defeated by the failure of an attempted Communist Party coup and the consequent deposition of Gorbachev. The Soviet Union splintered along national and ethnic lines; but when the economic situations of both the former Soviet Union and the United States continued to deteriorate, many in both nations looked back on the Cold War with nostalgia. When a new series of military and political coups resurrected the USSR, the United States was quick to join its former enemy in an alliance that established the supremacy of the two dominant nations over the rest of the world. The alliance was one of convenience rather than genuine friendship. . . .

The Exodus 2015–2050: In the first generation after the perfection of the Alderson Drive in 2010 more than forty planetary colonies were founded, not counting closed-environment mining settlements and refueling stops in systems without Terresteroid planets. While the CoDominium did not encourage governments (other than the US or Soviet Union) to establish direct settlements, corporations or settlement associations clandestinely backed by governments were common. Private colonization ventures were typically either commercial (e.g. Hadley, q.v.) or religious-ethnic in nature; see Arrarat (q.v.), Dayan (q.v.), Friedland (q.v.) , Meiji, (q.v.), others, spp. During this phase, several million emigrants left the solar system, almost all voluntary—although both the CoDominium Powers offered increasingly strong "encouragement" to politically inconvenient individuals and groups. Thus there are now planets whose population is purely Mormon (Deseret), American Black Separatist (New Azania), Russian nationalist (St. Ekaterina), Finnish (Sisu), and even Eskimo/Innuit (Nuliajuk).

The second phase of interstellar colonization began with the extension of the Bureau of Relocation's mandate to include involuntary transport of colonists (in addition to the already existing flow of convicts, many merely petty criminals). During this period (2040 to date) voluntary emigration has remained roughly stable, but involuntary has increased to levels exceeding fifteen million persons per year; at the same time, more than seventy new planetary colonies have been founded, many specifically by the Colonial Bureau as relocation settlements. Given the sometimes extremely marginal habitability of the planets concerned (see Haven, Frystaat) and the endemic shortage of capital in the outsystem colonies, casualties among the transportees are often heavy, with life expectancies averaging as little as three years in some cases.

Whump.

A globe of violet fire bloomed for an instant against the southern horizon, down in the lowlands, actinic brightness through the gathering dark and the light cold rain. Firefly streams of tracer began to stitch across the ground in long shallow arcs, and the reddish sparks of exploding munitions.

The mercenary sergeant smiled in satisfaction at the picture his facescreen showed. He turned in his foxhole, away from the action to the south and toward the valley below the ridge where his men lay concealed. The twelve-man SAS section was dug in on the low crest, invisible in their spider-holes under chameleon tarps. Only the thread-thin tip of the fiber-optic periscope showed above the sergeant's camouflage.

It was dark, Cytheria was just a sliver on the horizon, but that was no problem with nightsight. The enemy column was spread out down the wooded vale beneath them, winding through the tall grass and eucalyptus trees; the slope was in reddish-brown native scrub and shamboo. Men and mules halted at the sound of the explosion, then scattered to shouted orders.

"Now," Sergeant Taras Miscowsky said into the throat-mike. Not what the bastards expected, he thought with a hard grin in the private darkness of the hole.

A heavy droning whistle came through the low clouds overhead. Then: crump . . . crump . . . crump. Points of red fire flashed over the valley, proximity-fused 160mm mortar rounds bursting at ten meters up. Circles of vegetation bent away, crushed by blast and flayed by the steel-wire shrapnel. Men and animals screamed or writhed or lay still under the iron flail; faint bitter scent of explosive joined the smells of wet earth and grass. Another salvo came in, and another, the air whistling continuously. The observers called fire on the clumps of guerrillas forming around officers and noncoms, throwing men into panic flight and chopping into dog-meat any attempt to rally.

"That's doing it to them, Captain," Miscowsky said as he threw back the tarpaulin. Then more formally, "Sir, they're taking heavy casualties. I estimate thirty percent casualties on a full company. Better than half the mules are down, too. They're moving, one six five degrees true."

"Roger that. Tracking. We'll get the blocking group in fast."

"Sir. We'll lose most of them if we don't act fast."

"Right. Thank you, Sergeant."

Some of the enemy troops were moving straight west up the slope toward his position; the hill was gentle, and there was good cover. Mortar shells landed closer, probing for them as they moved up toward the ridge. The SAS unit was well dug-in, but they were infiltration scouts, not a line unit, and there were only a dozen of them. Miscowsky flashed a ranging laser at the center of the enemy group.

"Fire mission. Personnel, not armored. Five-fifty-six meters, bearing one hundred seventeen degrees."

"On the way," his commander's voice sounded in the helmet mike. Seconds later Corporal Washington spoke:

"Getting troop movement noise to our rear, Sarge. Multiples, light vehicles and infantry."

"Roger. Cap'n, the Royals are coming in from my west."

"Roger that, Miscowsky; the other side of the trap's moving in from the southeast around now."

Miscowsky turned his head in that direction and switched his facemask to IR sensors. There was a hell of a firefight going on down there a couple of klicks away, at the works the guerrillas had been planning to attack. Small arms, mortars . . . and the lance-shaped blossom of a Cataphract light tank's 76mm cannon. Several of those, coming toward him fast; he could see the faint waver of heat from their engines. Relayed sound-sensor data gave him the push from behind the SAS position. Boots thudding on turf, and a quiet whine from fuel-cell electrics. Then a louder shoop-wonk as their mortars opened up, lighter 8lmm's and 120mm mediums.

He tapped at the side of his helmet to switch to the Royalist unit's push.

"Miscowsky, Falkenberg's Legion," he said.

A dark machine shape came bounding up the low reverse slope behind him. A cycle, boxy body slung between two wheels that were balls of Charbonneau alloy monomolecular thread. It braked to a stop and a figure in bulky Nemourlon combat armor jumped down.

"Captain Lewis, 2nd Royals," the man said.

Others in the same camouflage uniforms and armor were swarming up the ridge; teams set up machine guns as the riflemen fanned out and opened fire. Behind them light four-wheel vehicles like skeletal jeeps hauled ammunition and heavy weapons, recoilless rifles and rocket-launchers.

Miscowsky straightened and threw a formal salute. "Sir. Falkenberg's Legion presents one enemy column, badly used," he said.

The Royal officer returned the gesture, grinning as he scanned the action below. His night-sight goggles were flipped up, and he was using a blocky pair of sensor-glasses; less efficient than the multitasking facemasks of the Legion, but Sparta was not a rich planet.

"Some of them are putting their hands up already," he said. A signals tech came up behind him and put a handset into his outstretched palm. "First platoon," he continued into it. "Deploy in skirmish order and advance. I want prisoners, but don't take unnecessary casualties. If in doubt, shoot." Men fanned out and began to filter into the scrub downslope.

"Well done, Sergeant," he went on, nodding to Miscowsky.

"Next insertion, sir?" Miscowsky said hopefully.

The Royal Spartan Army helicopter was still turning over its turbines behind the SAS squad.

"That's the last of them." Legion Captain Jamey Mace, Scout Commander, twitched his thumb toward the column of enemy prisoners as they shambled past under guard down to the river docks.

The Tyndos flowed north from here into the Eurotas, the great river of the Serpentine Continent. McKenzie's Landing was a riverside town, like most on this world; not much of one, which was also typical. There was an openpit rare-earth mine cut back into a smooth green hill, a geothermal plant and a kilometer of railway down to the loading docks. That and housing for a few hundred people, ranging from tufa-block Georgian houses for the mine-owner down to plastic-stabilized rammed earth for the miners' barracks. A fuel station by the docks, stacked logs for steamers and peanut oil tanks for diesels. A bar, a seedy-looking hotel, a Brotherhood meeting hall, two churches—established and non-conformist—and a tiny Hindi temple, a three-man Mounted Police station-cum-post-office. . . .

Not many of the Spartan People's Liberation Army—Helot—guerrillas had gotten to anywhere useful. Rosie's Bar and Grill was burning, and one of the steamers down at the pier was sinking at its moorings. The rebel plan had probably been to overrun the settlement just long enough to wreck the mine—it brought the Royal government off-planet hard currency—kill the Citizens resident, harangue the convict-transportee section of the labor force. . . .

"Let me go after them, Cap'n."

"Can't do that." Mace shook his head. "Back to training duty, Sergeant. We're going to need every Royal up to the mark—"

"Yes, sir, but—"

"If I thought there was one chance in ten thousand she was still alive I'd order you to go look for her."

"You wouldn't have to order me or anyone else. Captain, dammit, I know she's dead. But I want—"

"A head?"

"Balls would do."

"You'll have your chance," Mace said. It was easy to see what Mace was thinking. Taras Hamilton Miscowsky came from a culture that took blood feuds seriously. "Right now we've got a war to win, Sergeant."

'Sir." Miscowsky was silent; obedience, not agreement. Two months ago the war had stopped being a job to him; when Lieutenant Lefkowitz died. Lieutenant Deborah Lefkowitz, wife of Jerry Lefkowitz, who had been Miscowsky's first officer in the Legion. Miscowsky would not have lived past his first battle if Lefkowitz had not put his men ahead of his personal survival. Deborah Lefkowitz had been an electronics tech, not a combat soldier; sheer bad luck had put her observation plane over enemy Skyhawk missiles, in the Dales campaign. Miscowsky hadn't been able to rescue her, nobody had, after her plane augured in still spitting out data. Data that had probably saved the Legion's detachment here on Sparta, but nobody had saved Deborah. They found her torn clothing and some blood, but nothing else, despite the efforts of the Legion's best trackers.

That's the official story, Miscowsky thought. But Mendota was there, and he's not talking, and I think he found something more. Maybe the skipper has some reason to keep things to himself, but God damn—

Jerry Lefkowitz was far away, eight months interstellar transit, though only half that for the fastest messages, on New Washington with Colonel Falkenberg and the bulk of the Legion. Sparta had originally been intended as a quiet training assignment for the 5th Battalion and a haven for the noncombatants. He wouldn't even have the news about his wife yet. Miscowsky scowled. At least he wouldn't have to break the news. The chaplain-rabbi would do that. But I have to write him. And when I do I want an enclosure.

A man in the uniform of a Brotherhood militia captain came up. "Captain McKenzie, sir," he said to Mace. "Did I hear something about pursuit?" He was a middle-aged man, stocky and sandy-haired. There was a wolfish eagerness in his tone.

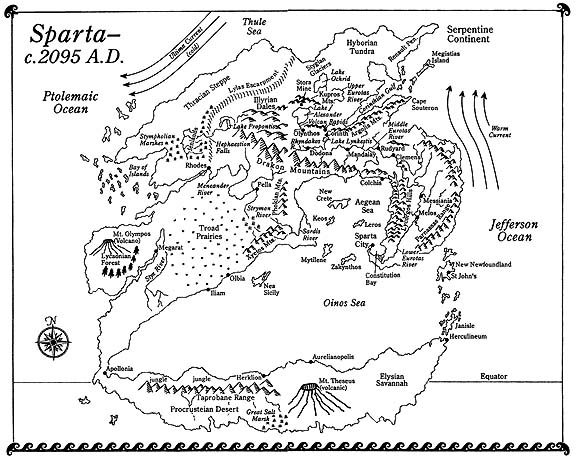

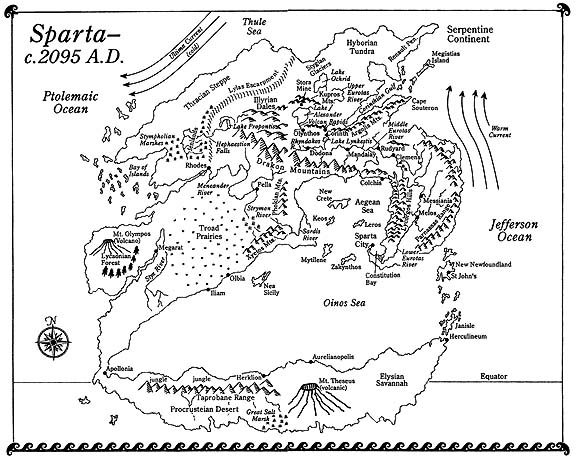

"The 18th Brotherhood's authorized to send fighting patrols into bandit country," Mace said, nodding northwestward. There lay the Himalayan-sized Drakon range and the vast forest-and-prairie expanse of hill country known as the Illyrian Dales.

"Not your SAS?" McKenzie said. He looked admiringly at the mercenary troopers squatting stolidly in the rain and leaning on their weapons. "We'd have been royally screwed if you hadn't spotted those terrorist scum massing up in the ravine country. We've only got an under strength company of the Brotherhood here; if they'd hit us without warning . . ."

Captain Mace pulled a pack of cigarettes out of a shoulder-pocket in his armor, offered one to the Spartan. They lit, sheltering their matches from the steady drizzle.

"That's just it," he said. "Look, the enemy never attack if they think we know they're coming; they just call it off and split up and concentrate somewhere we're not. And we can't give you long warning . . ."

They both nodded. Legion communications were secure—mostly—but the Brotherhood comm lines were leaky, and there didn't seem to be much that anyone could do.

Most of the three-million population of Sparta was spread out along the nearly ten thousand kilometers of the Eurotas. Most traffic moved at the pace of the riverboat, with the faster alternative being a blimp. There was very little high-tech transport; Sparta saved its money for building its industries, and imported little in the way of personal luxuries. Even military helicopters were still rare, just now starting to come off the lines in quantity. Away from the little towns and scattered ranches of the Valley were mountain, swamp, forest. Easy to hide in, now that the satellites were down. The Helots crept through it like rats in long grass, massing secretly, striking without warning and scattering before the Royalist forces could respond.

"It's like stomping on bloody cockroaches," the Spartan said in frustration. "Can't find the buggers. When you do, there are always more of them."

"Mm-hmm," Mace said. "And the Legion doesn't have enough SAS to make much of a difference. We've got to train your own Regulars, your SAS" —which in the Royal forces stood for Spartan Air Service— "to give you a broad-based capacity."

McKenzie nodded unwillingly. "We'll pursue anyway," he said. More softly: "My boy Phyrros was in the Dales. He got the Star of Leonidas . . . posthumously."

"Be cautious," Mace said.

"Sir." Miscowsky leaned forward. "Sir, I've been thinkin'." His provincial accent roughened a little, the Anglic harshened with the tones of Haven, his home planet. "Either the enemy's going downhill, or these were recruits. Prob'ly sent in for a little on-the-job training."

"Yes?" Mace looked at the prisoners thoughtfully.

A lot of them did look a little raw, without the stripped-down appearance you got after six months or so in Sparta's heavy gravity. Transportees. Convicts and political prisoners from Earth; most of the Helots were, like a majority of Sparta's population. And they did break up a bit easily. Not much unit cohesion, as if they were just out of the enemy equivalent of basic training. The Spartan People's Liberation Army probably hadn't expected much resistance here.

"Well," Miscowsky went on, "if this was a training exercise, they had a command group somewhere close watching. Might be worth going after, Cap'n. Maybe even that bastard nephew of Bronson's, the one we got the voiceprint on in the Dales."

That would be worth it, the mercenary officer thought. With Geoffrey Niles in our hands, we'd have more of a lever. Grand Senator Bronson was illegally backing the rebellion . . . not that anyone on Earth seemed to give a damn anymore about little things like the CoDominium's Laws of War, or treaties, or anything else.

"No." He shook his head. "Niles may be dead . . . or still wandering around the Dales looking for the Helot survivors. We've got orders; mount up, Sergeant."

Crack. A branch broke underneath a boot.

Geoffrey Niles started awake and then crouched lower under the overhang of blue rock. It was screened by tall canes of witch hazel and thick crystalline snow, only feet from the little brook that purled down the shallow valley under a skin of ice.

He forced his breathing to calm, clenching his jaw as it tried to chatter with cold and the effects of malnutrition. The skin on his fingers was cracked where it gripped the rifle; his body felt like an arthritic seventy instead of the twenty-eight Terran years it actually bore. Few would have recognized the sleekly handsome blond Englishman of a scant half-year before in the scarecrow figure that crouched in this cave. The heavy gravity of Sparta dragged at him, as sleep dragged at his eyelids. The air smelled of wet limestone and muddy earth; beyond the stream the first buds were showing on the rock maples, and strands of green among the yellow stalks of grass.

Another crack, and a voice swearing softly. Men dropped past him to stand on the edge of the stream, and another walked up it leading a flop-eared hound. Men in uniform . . .

Royalists, he thought. Camouflage uniforms, Nemourlon armor and helmets, but the shoulder-flashes showed Brotherhood militia. Not Royal Army regulars, and thank God not the mercenary SAS-scouts of Falkenberg's Legion. The relief was irrational, he knew; there were a dozen of them, and he had only five rounds left in the clip. The militia were countrymen used to tracking, and well-trained; they would check this overhang eventually. He had escaped from the last battle in the Dales by drifting downstream on a river that eventually fed into the Eurotas. It had carried him far into Royalist-held territory and it had been a long slow journey back into the wilderness.

I can't even blame Grand-Uncle for sending me here, he thought bitterly. He had asked to go to Sparta, to serve in the revolution Grand Senator Bronson was clandestinely backing. I wanted adventure. God!

"Lost him, Sarge," the man with the dogs said disgustedly. "He went into the creek downstream where it's clear, but I'm damned if I can find where he came out."

The militia noncom grunted. "Everyone, spread out; he may be lying low around here. And keep alert—we've come a long ways west, he isn't the only Helli around here. Sparks, get me—"

Pffft.

The soldier doubled over and fell backwards into the water with a red spot blossoming on his chest. The others went to ground in trained unison, scrambling back up the overhang to return fire. The sharp crackling of their New Aberdeen rifles echoed back overhead, answered by others out in the woods; the silenced sniper weapon fired again, and a light machine gun opened up on the Royalist patrol. A body slid back downslope to lie twitching at the edge of the water next to the bobbing corpse. Branches and scrub fell after it, cut by the hail of bullets; a man was screaming, an endless high keening sound.

Niles flogged his mind into thought. He had been running far and fast ahead of this pursuit; it was unlikely there was another Royalist patrol near enough to intervene. From the sound of the firing the guerrillas outnumbered the government soldiers handily, and according to Spartan People's Liberation Army—Helot—tactics they should . . .

God. If there still are any Helots— The attempted ambush in the Dales had fallen apart so fast the Royalists might have mopped up everything but scattered bands.

Fwhump. A rifle-grenade blasting off the muzzle of a rifle some distance away. It landed on the lip of the rise over his head and detonated in a spray of notched steel wire. Then more rifle fire came from the other side of the creek bed, into the backs of the Royalist soldiers, and more grenades. The noise rose to a crescendo and then died away with startling suddenness. Niles waited while the Helots made their cautious approach, waited until their leader whistled an all clear. Then he called out:

"I'm coming out! Senior Group Leader Geoffrey Niles, SPLA!" Spartan People's Liberation Army, the formal name of the Helots.

"Out careful," a hard voice replied.

He pushed through the witch hazel, leaving his rifle behind. The tough springy stems parted reluctantly, powdering him with snow. He stood with his hands raised. Half a platoon of Helot guerrillas surrounded him, most busy about their chores. A few leveled rifles at him.

"Police it up good, don't leave nothin' for the Cits," the Helot sergeant was saying. Men moved briskly, stripping the Royalist militiamen of weapons, armor, kit and clothing.

One Brotherhood fighter was still alive, despite the row of bullet-holes across the small of his back. The guerrilla noncom stepped up behind him as he crawled and fired with the muzzle of his rifle an inch from the back of the other man's head. The helmet rolled away in a spray of blood. Then he turned back to Niles.

"Who did you say—" he began, then stopped. His eyes widened as he recognized the scarecrow figure in the rags the winter woods had left of his uniform.

The sergeant was a short man, as were most of the guerrillas, a head shorter than the Englishman's 185 centimeters; virtually all of the guerrillas were transportees from Earth's Welfare Islands, chronically malnourished as children. American, from his accent, and Eurasian by the odd combination of slanted eyes that were a bright bottle green color.

"Jesus and Maria, it is Senior Group Leader Niles," he said, saluting and then holding out a hand. "Sergeant Andy Cheung, sir—hell, we thought you were dead meat for sure!"

"So did I for a while, Sergeant, so did I," he said. Relief shook him, and bitter regret. I wanted out, he thought. Out of the Helots certainly, after the horrors of the campaign last year; poison gas and slaughtered prisoners, capital crimes under the Laws of War. But the Royalists would hang him; the only chance he had of getting off this world alive was with the guerrillas. Off this world and back to a place where the Bronson power and wealth could buy immunity from anything.

"We gotta get out of here real quick," Sergeant Cheung was saying. "Lost half a platoon to them SAS buggers around here just last week; they're seven klicks of bad news." The noncom grinned at him. "Field Prime will sure be glad to see you again, sir."

Skilly, he thought, with a complex shiver. Oh, God.

"Are you telling me, gentlemen, that there is nothing we can do to rid our world of these murderous vermin?"

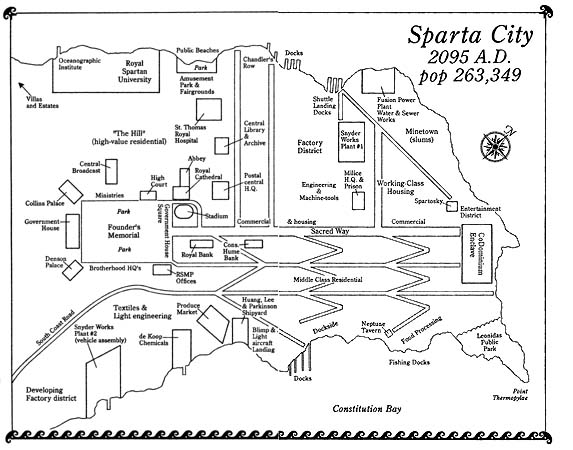

Crown Prince Lysander Collins paced back and forth before the broad windows that looked out over Government House Square; the Council Chamber where the Cabinet met was on the second floor of the Palace. It was a rainy spring day, and the breeze carried in odors of wet vegetation from the gardens, together with a damp salty smell from the Aegean. He was a tall young man in his mid-twenties, with short-cropped brown hair and regular features. Until recently it had been a rather boyish face.

Peter Owensford, Major in Falkenberg's Legion, Major General in the Spartan Royal Army, looked up from his readout and files to the prince. Not so young as he was.

A good deal had happened to Crown Prince Lysander Collins over the past eighteen Terran months. Sent to the CoDominium prison-planet of Tanith as unofficial ambassador to Falkenberg's Mercenary Legion; he had "seen the elephant" there, as a volunteer junior officer, and incidentally earned the respect of many of the Legion officers. Owensford suspected Lysander Coffins would have been more than happy to maintain his pseudonym of "Mr. Cornet Prince" and remain in the Legion's ranks. That was impossible, of course, despite Lysander's bravura performance, highjacking the rebel shuttle and the smuggled drugs . . . as impossible as his brief and doomed affair with Ursula Gordon, sometime hotel girl on Tanith. Sparta was too important to civilization, and to the plans of Grand Admiral Sergei Lermontov, for Lysander Collins to have any role but the straight one laid out for him by hereditary duty. If there's to be any civilization left once the CoDominium collapses.

Lad's grown up a lot, Owensford thought. Lysander had returned to Sparta to find a full-fledged rebellion in progress. Did all right, too. Decent as battalion commander. Even better as field commander in chief. I've fought for worse ones. Now even that was denied him; with his father's judgment impaired by the enemy's viral sabotage he was de facto ruler of the Collins half of the Dual Monarchy's executive. He's seen the elephant with a vengeance.

"No, sir," Owensford said aloud. "There is a great deal that we can and must do."

The Crown Prince was in uniform at this meeting; as a Lieutenant General, he could be addressed as a military superior rather than sovereign, a useful fiction. "But I am saying for the record that under present conditions it will be very difficult to achieve swift and decisive victory over the enemy."

He looked over at Hal Slater, the other mercenary present. Commandant of the Royal War College, making him a Major General in the Royal Army. Possibly a more permanent one. Owensford would revert to his mercenary rank of Major whenever the Fifth Battalion of Falkenberg's Legion left Sparta . . . if they left; quite probably this would be permanent base for at least part of the mercenary outfit. And I'm running a whole army here. Challenging. Long-term if he wanted to stay here and become a Spartan Citizen. Tempting. Sparta's a good place, and I'm tired of running from planet to planet. Owensford looked again at Prince Lysander. He's grown up. I could accept him as sovereign. I think Hal already has.

Hal Slater wouldn't be filling any active commands. He had gone to the regeneration tanks once too many times, too many bones were titanium-titanium matrix, and his wounds would keep him behind a desk for the rest of his life. Running the War College was a good final berth. One he would do well; Hal Slater had taught Owensford and many another young officer, back in his days with the Legion. His son George was a Legion Captain, and a Brigadier in the Royal forces.

And Hal Slater is Falkenberg's oldest friend. If anyone knows what Falkenberg's game is, Slater will.

Lysander halted at the window and looked out over the square. "I had hoped to get more out of the Illyrian Dales campaign," he said bitterly. "We certainly paid enough for it."

Owensford nodded. The battles against the Helots in the northwestern hills had been bloody. Bloodily victorious, in the conventional sense . . . and a good deal of that was due to Crown Prince Lysander's refusal to accept a truce offered by the enemy when the battle was won. That had cost the Royal Army, but they had harried the enemy units into rout with a relentless pursuit. Lysander, he knew, was still haunted by the casualties. They'd lost some of those wounded in the enemy's poison-gas attacks, because many couldn't be flown out while the battle continued.

"We paid, but never doubt it was worth it," Owensford said. He looked to Slater and got a nod of agreement. "I doubt if one in five of the enemy escaped on the southern front. High cost in their trained leaders."

"Not enough to break them," Lysander said.

"No, sir. But we stopped them. Sir, they were in a fair way to taking and holding a good part of the Dales. That would have given them a sanctuary area. More than that. It would have given them a territory making this an actual planetary war instead of an insurgency. They could have called on the CoDominium to intervene. Depending on CD politics that might even have worked. Instead, we got most of their leaders, maybe half of their lower ranking Meijian technoninjas, a lot of their equipment. Some of their units evaporated. Lots of deserters. One unit surrendered just about to a man."

"Good recruits?" Hal Slater asked.

Owensford nodded.

Prince Lysander frowned. "You're accepting Helots as military volunteers?"

Owensford grinned slightly. "Not for you, sir. For the Legion. We'll get them part trained and ship them off as reinforcements for Colonel Falkenberg on New Washington. The point is, sir, don't doubt that you made the right choice. We not only robbed them of their victory, we came close to breaking them."

Slater said, carefully, "It should have been enough to break them."

"But it didn't."

"No, sir," Peter Owensford said. "They've got too much off-planet support."

"Not just off-planet."

"No, sir." A sore point: Sparta hadn't yet suspended constitutional civil rights, and the Helots had allies in the Senate and elsewhere.

"Look at it this way. You forced them back to classical Phase One guerrilla operations," Hal Slater said.

"Vigorous Phase One operations," Owensford said.

"Well, yes," Slater said. "It hurts, but Phase One can't win if you keep your nerve."

Lysander slammed the heel of his hand against the stonework. That was the antiseptic Aristotelian language of a military professional; "Phase One" meant ambush and sabotage, burnt-out ranches and civilians killed by land-mines, every sort of terrorist atrocity.

He looked at Slater. "This is what you meant at the first Royal Strategy Lecture, isn't it?" He quoted: "'Insurgency against a modern state requires powerful allies operating from sanctuary. Unfortunately, given supply of war material from a sanctuary, insurgency can be continued practically forever.'"

"Yes, sir," Hal Slater said. "Under the present circumstances, patience is as important a weapon as explosives." He shrugged. "It's also all we have just now."

Lysander nodded curtly. Both the professionals were older than he—Owensford in his thirties, Slater over fifty—and between them they had a generation's experience. He would use that accumulated wisdom.

"I agree. I don't have to like it," he said. "What else can we do?" He held up a hand. "Not tactics, that's obvious—what can we do to bring the war to an end?"

Slater smiled thinly; it was not every man Lysander's age who could keep the need to have strategy driving tactics firmly before his mind.

"There are essentially three ways to defeat an enemy," Slater began formally. Teaching had been a large part of his military career, even before he became head of the Spartan War College. "Physically smashing them is one—killing so many that the remainder give up in despair. We can only do that with the Helots if they are obliging enough to gather in one place where we can get at them. They nearly made that mistake last year in the Dales, but I doubt they will again. Their leaders are evil men—"

And women, Owensford thought; he remembered the mocking contralto voice of the Helot field commander in the Dales, with its soft Caribbean accent. By the look on his face, so did Lysander. Neither of them had forgotten the helpless prisoners slaughtered on her order.

"—evil to the point where 'vile' is an appropriate term, but they are not stupid. Inexperienced in real warfare, but they are cunning, they have experienced mercenary advisors, and they learn quickly."

Slater sipped water and continued. "As is often the case in war, we cannot force battle on the enemy if they are not willing to meet us; the ratio of force to space is too low. There is nothing they must stand and die to defend; they have no towns, farms or families as the Royal forces do, and no base of supply." Slater paused. "None within our reach, anyway."

Sparta had three million people, a tenth of them in the capital; the Serpentine Continent had eighteen million square miles of territory. Even the heartlands along the Eurotas River were thinly peopled.

"Particularly with the limits on surveillance, we are unlikely to catch large numbers of them at any one time." Skysweeper missiles had knocked down every attempt to loft more spy satellites; observation aircraft were impossible, of course, and even drones were high-cost and short-lived if the enemy had countermeasures. In addition, the Helots' Meijian hirelings were simply better at electronic intelligence and counter-intelligence than anything the Dual Monarchy of Sparta could afford, and they were running rampant through every computer on the planet with the exception—he devoutly hoped—of the Legion's. At that, his own electronics specialists were spending a counterproductive amount of time checking for viruses and taps, and vetting Royal Army machines. The Royalist forces were back to what scouts and spies could discover, and whatever the Legion computers could massage out of the data.

"Of course there's an unpleasant implication to our lack of surveillance," Slater said. "Low orbit satellites they can knock down fairly easily, but geosynchronous? They had to have cooperation from the CD Navy for that."

"Are you sure?" Lysander demanded.

"Near enough," Slater said. "The CD may not have knocked our geosynch out, but they had to look the other way when it happened. And you'll note they haven't offered to replace it."

"No. When we ask for cooperation, they never say 'no,' but nothing happens. Delays, red tape, forms not properly filled out . . . Do you think they're actively against us?"

Slater shrugged. "Or tilted neutral at best."

"What can we do about that?"

"I presume you've filed a formal protest."

Lysander nodded. "And you?"

"We've done what we can," Peter Owensford said. "I've sent off urgent signals to Falkenberg and Admiral Lermontov. With any luck Lermontov can use this to order active CD intervention on our side."

"How did you send the message?" Lysander asked.

"With your permission I would rather not say," Owensford said.

Lysander nodded quickly. "That's probably best. Do you think we can get CD Navy support? When?"

Hal Slater shook his head. "It won't be soon. CD politics is thick soup." His voice went back to lecture mode. "The second method of defeating an opponent is to strike at their rear—at the sources of their supplies and support. Unfortunately, we cannot for the same reason we can't locate them. As long as they have even tacit CD support, their rear area is off-planet."

"Bronson," Lysander said; he made the word an obscenity.

"Exactly. Grand Senator Bronson. Somehow Bronson's people are still landing supplies. His shipping lines regularly transit Sparta's system, and the supplies get here. It's like the geosynchronous satellites. We have no proof, but it's hard to imagine any other explanation."

The Treaty of Independence had left spatial traffic control in the hands of the CoDominium forces, and the Grand Senator was a power in the CoDominium. So were Sparta's friends—Grand Admiral Sergei Lermontov and Grand Senator Grant, the Blaine family . . . and the result was deadlock. No new thing. It was a generation since the CoDominium as a whole had been able to do anything of note. The Soviet Union was dissolving again—but so was the United States. Between them they ruled the world, but neither nation remembered why they had wanted to.

"Bronson," Slater went on, "is also behind most of our economic problems."

Sparta's main exports were minerals and intermediate-technology products for planets even less industrialized than she. Markets had been drying up, contracts been revoked, suppliers defaulting, loans being called due. The planetary debt was mushrooming, and Standard and Poor's had just reduced the Dual Monarchy's credit rating once more. The financial community was more and more jittery over the situation on Earth, in any case. Capital was flowing out to the secure worlds, places like Friedland and Dayan, and sitting there.

"What does Bronson want?" Lysander demanded.

Hal Slater shook his head. "We don't know."

"He seems to have an active hatred for Falkenberg."

"Yes, sir," Slater said. "But that's a very old story."

"Falkenberg ruined his Tanith operation," Lysander said.

"Yes, sir. With your help." Slater shrugged. "Bronson never forgets an enemy. You'll have noticed that he hasn't even tried to negotiate with you. But given the resources he's putting into this operation, there has to be more at stake than personal animosity. Unless—"

"Unless?"

"Unless he's feeling old and useless and has nothing left but his hatreds," Slater said.

"Whatever his motives, this has to stop." Lysander stared out at the Spartan landscape. "Even if we called out every Brotherhood militiaman," he said slowly, "we wouldn't have enough to finish this quickly. Would we?"

"No, sir," Owensford replied flatly. "They'd disperse, go to earth and wait for new supplies. We can't keep any militia unit in the field for more than a month or so. Helot attacks are planned long in advance; if we detect them concentrating and mass to defend or counterattack, they simply call off their assault and pick another target somewhere else. They never attack without a locally superior ratio of forces, and we don't have enough mechanical transport to respond quickly in such cases."

There were a million Citizens; the first-line militia of their Brotherhoods could field a quarter of a million troops. Unfortunately, when they did the entire planet had to shut down; the Citizens were over a third of the total labor force, and a much higher percentage of the skilled and managerial classes.

"We're keeping fifteen battalions under arms at any one time as regional reaction-forces, and we're building up the standing forces of the Royal Army to twenty-five thousand troops," Owensford said. He ran a hand over his short-cropped brown hair. "Whatever else the Dales campaign did, it certainly gave us plenty of combat-tested men." Action was the best way to identify potential small-unit leaders. "And the cream of the newcomers as recruits, too. Everyone wants to fight for a winner. We'll keep grinding at the enemy."

Hal Slater grimaced slightly. "Now you see why professionals hate guerrilla wars, sir," he said. "It's pure attrition, unless we can kill or capture their top leaders."

Lysander smiled sourly. "I've known mercenaries who liked that kind of thing. A long war and no resolution—no, of course I don't suspect that of Falkenberg."

Slater didn't say anything.

"All right," Lysander said. "Attrition with Grand Senator Bronson sending the Helots weapons and money, and the CoDominium Bureau of Relocation sending convicts and involuntary transportees for them to recruit from. It takes twenty years to produce a Citizen, gentlemen, and only eight months to ship a transportee from Earth to Sparta. And yes, I know, you can recruit among those as well as the enemy. But damn it, no offense intended, Sparta needs Citizens, not more mercenaries."

He moved his shoulders, the unconscious gesture of a man settling a burden he means to carry. "We can also proceed on the political front," he went on. "Breaking up the enemy's clandestine networks. And nailing Croser."

For a moment all three men shared a wolfish grin. Senator Dion Croser, head of the Non-Citizen's Liberation Front . . . and almost certainly leader of the whole insurrection. Almost all the insurgents were transportees and non-Citizens; Croser was the son of one of the Founders, and there was as yet no smoking-gun proof of his involvement with the insurrection.

"He won't be the last," Lysander went on softly. Even the mercenaries were slightly daunted by the look in his grey eyes. "We can't attack a man who's a power in the CoDominium—we can't even defy the CoDominium—yet. But Croser we will get; and eventually, beyond him, those responsible for backing him. As God is my witness, I'm going to see that nobody is ever in a position to do this to Sparta again. Or," he went on, "to anyone else, if I can help it."

"Meanwhile," he continued more briskly, "we should prepare for the War Cabinet meeting."

The rain had been hitting harder as the Helot patrol moved northwest. The horses hung their heads slightly, wearily placing one hoof down at a time. For Geoffrey Niles the trip was rest and recuperation, after starving and freezing for the better part of two months. By the end of the second week he was strong enough to curse the cold drops that flicked into his face as they rode and trickled down inside his camouflaged rain-poncho, to realize how much he detested the constant smells of wet human and horse. The forest thickened as they moved closer to the foothills of the Drakons, spreading up from the low swales and valleys to conquer the slopes of the hills, leaving only patches in the tallgrass prairie that was so common elsewhere in the Illyrian Dales. Occasionally they passed other patrols—once they nearly tripped an ambush—and more often saw foraging parties, out cropping the vast herds of game and feral cattle.

"Not many enemy in this far?" he asked the Helot NCO.

"No, sir," the man replied he kept his rifle across his saddlebow, and his eyes were always moving. "Leastways, not big bunches of 'em. Sometimes they send in fightin' patrols, battalion or better, but we scatter an' harass and they go away. Hard to supply this far in, too. They got no satellite recce now, can't put aircraft anywhere near us. Keep tryin' t'locate our bases, though. Lots of infiltrators. Ambush and counter-ambush work—helps with training the new chums, anyway."

Niles nodded. They were riding up a long slope; the rain had a little sleet in it now, they must be at least a thousand meters above sea level. Well into the foothills, and Sparta's 1.21 G gave it a steep atmosphere and temperature gradient. The slopes on either side were heavily wooded with Douglas fir and Redwoods, oaks and beech; the genetic engineers and seeders had done their work well here. Branches met overhead, and the hooves clattered through gravel and broken rock. They turned a corner; it took a moment's concentration for Niles to pick out the bunkers that flanked the pathway. They were set deep in the lime, with narrow firing slits hiding the muzzles of 15mm gatlings. His shoulders crawled slightly with the knowledge that Peltast heavy sniper-rifles had probably been trained on them for the better part of an hour.

"Sir," an officer said, as he swung down from the saddle. "We've got transport for you. Field Prime is anxious to debrief you herself."

Niles raised a brow at the sight of the jeep; it was a local model, six balloon-wheels of Charbonneau thread, but the Helots had had little mechanical transport before. We're coming up in the world, he thought.

The new base-headquarters was a contrast to the old, as well. It was a rocky bowl several kilometers in extent, a collapsed dome undercut by water seepage. That was common in the Dales, with multiple megatonnes of water coming down off the Drakon slopes every year and hundreds of thousands of square kilometers of old marine limestones to run through. The edges of the ring were jagged fangs thrusting at the sky; his eyes widened at the sight of detection and broadcast antennae up there, and launching frames for Skyhawk and Talon antiaircraft missiles. Cave-mouths ringed the bowl, busy activity about most, but the rolling surface itself was occupied as well.

Not afraid of aerial surveillance any more, he thought. Neat rows of squared-log cabins, and troops drilling in the open. More troops than he expected, many more, but what was really startling was the equipment. Plenty of local make, everything from rifles and machine guns up to the big 160mm mortars that were the local substitute for artillery; Dion Croser had been siphoning off a share of local production and caching it in cave-dumps here in the Dales for a full decade before the open war began. But there was off-planet material as well, in startling quantity, items he remembered from Sandhurst lectures. A dozen stubby 155mm rocket-howitzers, Friedlander-made, with swarms of Helot troopers around them doing familiarization. Six Suslov medium tanks, slab-and-angle composite armor jobs with low-profile turrets and 135mm cannon in hydraulic pods. Those were CoDominium issue, made on Earth.

And bloody expensive, he thought.

The jeep pulled up at one of the cave entrances. A man was waiting for him. Niles recognized the figure; 190 cm tall and broad enough to be squat. Skin the color of old mahogany, a head bald as an egg, and a great beak of a nose in the round face. Over his shoulders were the twin machetes that had given him his nickname, and dangling from one hand was a light machine gun looking no bigger than a toy rifle in the great paw. The only change he could see was a certain gauntness to the face.

'Two-knife," he said, nodding to the Helot commander's right-hand man.

"Niles," the other answered, equally polite and noncommittal. The big Mayan had not minded when Skilly took the Englishman as her consort; that was the Donna's privilege. Niles was privately certain that he would also have no hesitation in quietly killing an unworthy choice. . . .

The caves were larger than the old Base One that had fallen to the Royalists last winter, but the setup within was similar, down to the constant chill and smell of wet rock. Glowsticks stapled to the walls, color-coded marker strips, occasional wooden walls and partitions, rough-shaping with pneumatic hammers. There seemed to be a lot more modern electronics, though. He passed several large classroom-chambers with squads of Helots in accelerated-learning cubicles, bowl-helmets over their heads for total-sensory input. Then they went past alert-looking guards into a still larger chamber, where officers grouped around a computer-driven map table. One looked up at him.

"Hiyo, Jeffi," she said quietly when he was close enough to salute.

Geoffrey Niles' throat felt blocked. He had thought he remembered her, but Skida Thibodeau in the flesh was something different from a memory. Very tall, near two meters, much of it leg. Muscled like a panther and moving like one, a chocolate-brown face framed in loose-curled hair that glinted blue-black. High cheekbones and full lips, nose slightly curved, eyes tilted and colored hazel, glinting with green flecks. His nostrils flared involuntarily at her scent, soap and mint and a hint of the natural musk. And the remembered thrill of not-quite-fear at meeting her eyes, intelligent and probing and completely feral.

"Skilly is glad to see you back," she said.

"Glad to be back, Field Prime," he said. Realized with a slight shock of guilt that it was true. God, what a woman.

She smiled lazily, and sweat broke out on his forehead; then she dropped her gaze to the map table. "We having de post-mortem," she continued. "Little training attack go wrong, a bit."

He cleared his throat, looked around at the other officers. Many he recognized: von Reuter, the ex-CD major; Sutchukil, the Thai aristocrat and political deportee, a man with a constant grin and the coldest eyes Niles had ever seen. Kishi Takadi, the Meijian technoninja liaison. Another man he almost did not recognize. Chandos Wichasta, Grand Senator Bronson's trouble-shooter. That was a shock; the last time he had seen the little Indian was back on Earth, during the humiliating interview with great-uncle Adrian at the Bronson estate in Michigan. The Spartan mission had been a last chance to redeem himself . . . Which means Grand-Uncle has managed to get two-way communication going. There were big glacial lakes in the Drakon foothills where high-powered assault shuttles could land and take off.

"Brigade Leader Niles," Wichasta said discreetly. Another surprise; Niles had been Senior Group Leader—roughly a Major—in the SPLA in the last campaign.

Skilly smiled and shrugged. "You was right about Skilly's plan last time, Jeffi," she said. "Too complicated; or maybe we have de intelligence leak here. Or both; Skilly think both. Howsoever, de wise mon learn from mistake."

"Ah . . ." Come on, you bloody fool, don't sound like a complete nitwit " . . . things seem to be well in hand."

Skilly nodded. "Numbers back up some," she said judiciously. "Lots more fancy off-planet stuff coming in—" she nodded to Wichasta "—and money, lots of money. The Royals, they doan' know how much we have hid, too. We bleeding them pretty good now, gettin' ready we give them the real grief."

"Hmmm. Won't the CoDo naval station on the Aegis platform—" He broke off at the ring of wolfish grins around the map table.

She laid her light-pencil down. "Field Prime think that enough analysis," she said. "Von Reuter, you breaks up that group and uses the personnel at you discretion." She looked at Niles, and the pulse hammered in his temples. "Brigade Leader Niles need a debriefing."