I'm delighted that someone is making Christopher Anvil's work available once again. Especially the Interstellar Patrol stories. Vaughan Roberts, Morrissey, and Hammell have always been three of my very favorite characters, and I've always loved Anvil's . . . peculiar sense of humor.

I suppose, if I'm going to be honest, that Roberts' J-class ship is another of my favorite characters. In fact, although I hadn't realized it until I sat down to write this introduction, I suspect that there was a lot of the Patrol boat's computer hiding somewhere in the depths of my memory when I created Dahak for the Mutineers' Moon series. After all, Dahak is simply another self-aware ship kidnapping itself a captain on a somewhat larger scale. They even have a few personality traits in common.

The characters themselves are always a delight in an Anvil story or novel. Like most good character builders, Anvil creates his memorable people for the reader through their interactions, and the edge of zaniness which seems to creep into almost everything he writes only makes them even more interesting. His pronounced gift for building larger-than-life planets and environments for them to interact in sometimes seems to slip past almost unnoticed, yet it is a constant in almost all of his stories, and I think it is one of his strongest building blocks. He also has more than a touch of the Eric Frank Russell school of "poor aliens" in his work, because whoever sets out to oppose or overcome one of his characters has all unknowingly set his foot on the first slippery step of the slope of doom. The only question is how big a splat the villain is going to make at the foot of the cliff. This shows strongly in the first volume of Anvil's work from Baen Books, Pandora's Legions, but it makes its appearance in this volume, as well. In this instance, however, most of the "poor aliens" are actually "poor humans," with a sizable smattering of unfortunate master computers, robotic police units, and nasty extraterrestrial fauna thrown in for good measure.

In many ways, Anvil's storytelling style has always reminded me of the historical romance novels by Georgette Heyer or Lois Bujold's Miles Vorkosigan stories. Like Heyer and Bujold, Anvil's characters always have a perfectly logical reason for everything they do, yet they slide inevitably from one catastrophe to another in a slither which rapidly assumes avalanche proportions. A Keith Laumer character triumphs through an unflinching refusal to yield which transforms him, permits him to break through to some higher level of capability or greatness. An Anvil character triumphs by shooting the rapids, by caroming from one obstacle to another, adapting and overcoming as he goes. In many ways, his characters are science-fiction descendents of Odysseus, the scheming fast thinker who dazzles his opponents with his footwork. Of course, sometimes it's a little difficult to tell whether they're dazzling an opponent with their footwork, or skittering across a floor covered in ball bearings. But Anvil has the technique and the skill to bring them out triumphant in the end, and watching them dance is such a delightful pleasure.

The stories in this volume are science-fiction in the grand, rip-roaring tradition. Anvil throws around powerful bureaucracies like the PDA, huge space navies like the Space Force, and deviously capable guardians of the Right and Good (although said guardians may be just a mite tarnished around the edges) like the Interstellar Patrol. He delights in creating obscure, complex, often many-sided conundrums for his characters, and then taking us with him as they unravel the problem one strand at a time. I see a lot of the Golden Age in his stories, echoes of Williamson's Legion of Space, or of John Campbell's Arcot, Wade, and Morey in the scale and the sweeping, half-laughing scope of the problems he inflicts upon his characters. And most delightfully of all, in our post Star Trek universe, there isn't a trace of the Prime Directive. There are only characters with wit, humor, courage, and rather more audacity than is good for them.

While it is inevitable that any volume which is going to deal with Vaughan Roberts & Co. has to start with "Strangers to Paradise," that story—excellent as it is—was never really my favorite Interstellar Patrol story. I'm not sure why. Perhaps it's because the "want-generator" is a bit too much like Williamson's AKKA super weapon in the Legion of Space stories. Or perhaps it's because the "want-generator" is a little too much of the one aspect of Anvil's stories which sometimes disturbs me on a philosophical level. His characters, by their nature, are the sort of people who set out to fix problems, yet sometimes the means they embrace fringe just a little too closely upon a sort of intellectual totalitarianism. Not in terms of ideology per se, but in the willingness to manipulate and control in ways which cannot be resisted. At the same time, however, Anvil is always careful to show the pitfalls of such an approach, as in "Strangers to Paradise" itself, when the subjects of our heroes' "mind control" stubbornly persist in doing something their controllers never counted on.

Yet whether or not "Strangers to Paradise" would make my own list of top five Anvil stories, it is most definitely the direct and necessary progenitor of what undoubtedly are my two favorite IP stories: "The King's Legions," which is included in this volume, and the short novel Warlord's World, which is not but which I hope and expect will be along shortly. It's always seemed to me that, just as Laumer's novella "The Night of the Trolls" captures the essential Laumer hero perfectly, "The King's Legions" and Warlord's World capture the essential Anvil.

For those of us who have known Anvil for years, this book is a most welcome reunion with old friends. For those not already familiar with him, it offers an introduction to a writer and to characters very much worth knowing. In some ways, I rather envy the reader who is about to experience his or her first, concentrated dose of Anvil-dom. If you're one of those newcomers, welcome aboard. Whichever Anvil tale winds up your favorite, at least you'll have a rich and varied selection to choose from. This volume contains many of my favorites, but there's a lot more Anvil out there, and I hope that Baen will bring more of it to us. In the meantime, you hold in your hands an excellent starting point.

Buckle up tight. It's going to be an . . . energetic ride.

Without a doubt, Christopher Anvil's richest and most developed setting was what he and John Campbell—who edited Astounding/Analog magazine where most of the stories originally appeared—called "the Colonization series." Anvil wrote over thirty stories in that setting, ranging in length from short stories to the novel Warlord's World.

At the heart of the Colonization series are the stories concerning the Interstellar Patrol, which are the best known. But Anvil wrote a number of stories in the same setting, in which the Interstellar Patrol does not figure directly. These stories often involved such organizations as the Space Force, the Planetary Development Authority and the Stellar Scouts, the Space Navy—and a wide range of civilians, from big businessmen to merchant spacemen to colonists on the ground.

Often enough, characters who appear in cameo or minor roles in the Interstellar Patrol stories are the protagonists of other stories. An example is the ruthless businessman Nels Krojac, who is only mentioned in passing in "The King's Legions" and "The Royal Road" but is a central figure in "Compound Interest" and "Experts in the Field."

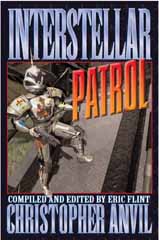

In this volume, we are reissuing the first two major episodes of Anvil's Interstellar Patrol adventures, as well as—in Part III—a number of stories which give the reader a sense of the setting as a whole.

—Eric Flint