Can anything be more burdensome than maturity? To be saddled by it, day in, day out, offering "wisdom" that may not be heeded . . . or even needed. Always the parent. Always the party pooper. That is, when anybody listens at all.

Patience. That's what I require most, every day that I am on this job. No father or mother, teacher or playground guardian ever needed more than I do, as the human advisor aboard a mighty interstellar cruiser, operated by several hundred brash, rambunctious, impulsive, affectionate, abrasive and maddening Demmies.

Take the time our good ship—Clever Gamble—entered orbit above a planet of the system, Oxytocin 41.

I was at my science station, performing routine scans, when Captain Olm inquired about signs of intelligent life.

"There is a technic civilization, sir," I replied. "Scanners observe a sophisticated network of roads, moderate electromagnetic activity, indicative of—"

"Never mind the details, Doctor Montessori," the captain interrupted, leaping out of his slouch-chair and bounding over to my station. At almost five and a half feet, he was quite tall for a Demmie. Still I made certain to stoop a little, giving him the best light.

"Are they over sixteen on the Polanski Scale?" he asked urgently. "Can we make contact?"

"Contact. Hmm." I rubbed my chin, a human mannerism that our crew expects from their Earthling advisor. "I would say so, Captain, though to be precise—"

"Great! Let's go on down then."

I tried entreating. "What's the hurry? Why not spend a day or two collecting data? It never hurts to know what we're stepping into."

The captain grinned, belying his humanoid likeness by exposing twin rows of brilliant, pointy teeth.

"That's all right, Advisor, I've had slippery boots before. Never stopped me yet!"

The crude witticism triggered laughter from other Demmies in the command center. They often find my expressions of caution amusing, even when I later prove to be right. Fortunately, they are also fair-minded, and never confuse caution with cowardice.

Around a starship crew of Demmies, the human advisor can feel free to act "prudently wise," since this is true to the image they have of us.

But never display outright fear. They find it upsetting. And we don't want them upset.

"Break out the hose!" Captain Olm commanded, rubbing his hands. "Tell Guts and Nuts to meet us at the spigot. Come on, Doc. We're going down!"

Demmies love nicknames. They have one for the human race, often calling us "the Ancient Ones."

From their point of view, it's obvious. Not only do we live much longer as individuals, with lifespans of ninety or more Earth years, but from the Demmie perspective our people have been roaming the galaxy since time immemorial.

Well, after all, most member-races of the Federated Alliance learned starflight from us . . . as Demmies did, when we contacted their world fifty-eight years after our first starships departed the solar system.

That's how much longer we roamed the star lanes. Fifty-eight years. And for this they deferentially call us the Ancient Ones.

Sure. Why not? The first rule to remember—a rule even more important than the Choice Imperative—is to let Dems have their way.

Alliance spacecraft look strange to the uninitiated.

Till recently, most starfaring races traveled in efficient, globelike vessels, with small struts symmetrically arranged for the hyperdrive anchors. Travel to and from a planetary surface took place via orbital elevator at advanced worlds, or else by sensible little shuttles.

Like any prudent person, I'd be far happier traveling that way, but I try to hide the fact. Demmies cannot imagine why everyone doesn't love slurry transport as much as they do. So you can expect it to become the principal short-range system near all Alliance worlds.

It's not so bad, after the first hundred or so times. Trust me. You can get used to anything.

As a Demmie-designed exploration ship, the Clever Gamble looks like nothing else in the known universe. There are typically garish Dem-style drive struts, looking like frosting swirls on some psychotic baker's confection. These are linked to a surprisingly efficient and sensible engineering pod, which then clashes with a habitation module resembling some fairy-tale castle straight out of Hans Christian Andersen.

Then there is the Reel.

The Reel is a gigantic, protruding disk that takes up half the mass and volume of the ship, all in order to lug a prodigious, unbelievable hose all over the galaxy, frightening comets and intimidating the natives wherever we go. This conduit was already half-deployed by the time the ship's artificer and healer met us in the slurry room. Through the viewer, we could see a tapering line descend toward the planet's surface, homing in on a selected landing site.

The captain hopped about, full of ebullient energy. For the record, I reminded him that, contrary to explicit rules and common sense, the descent party once again consisted of the ship's top four officers, while a fully trained xenology team waited on standby, just three decks below.

"Are you kidding?" he replied. "I served on one of those teams, long time ago. Boringest time I ever had."

"But the thrill of contacting alien—"

"What contact? All's we did was sit around while the top brass went down to all the new planets, and did all the fighting and peacemaking and screwing. Well it's my turn now. Let 'em stew like I did!" He whirled to the reel operator. "Hose almost ready?"

"Aye sir. The Nozzle end has been inserted behind some shrubs in what looks like a park in their biggest city."

I sighed. This was not an approach I would have chosen. But most of the time you just have to go with the flow. It really is implacable. And things often turn out all right in the end. Surprisingly often.

Olm rubbed his hands. "Good. Then let's see what's down there!"

Resignedly, I followed my leader into the dissolving room.

At this point I should introduce Guts and Nuts.

Those are not their formal names, of course. But, as a Demmie would say, who cares? On an Alliance ship, you quickly learn to go by whatever moniker the captain chooses.

Commander-Healer Paolim—or "Guts"—is the ship's surgeon, an older Demmie and, I might add, an exceptionally reasonable fellow.

It is always important to remember that both humans and Dems produce individuals along a wide spectrum of personality types, and that the races do overlap! While some Earthling men and women can be as flighty and impulsive as a Demmie adolescent, the occasional Demmie can, in turn, seem mature, patient, reflective.

On the other hand, let me warn you right now—never get so used to such a one that you take it for granted! I recall one time, on Sepsis 69, when this same reasonable old healer actually tried to persuade a mega-thunder ameboid to stop in mid-charge for a group photo. . . .

But we'll save that story for another time.

Commander-Artificer Nomlin—or "Nuts"—is the ship's chief engineering officer. A female Demmie, she dislikes the slang term, "fem-dem," and I recommend against ever using it. Nuts is brilliant, innovative, stunningly skilled with her hands, mercurial, and utterly fixated on making life miserable for me, for reasons I'd rather not go into. She nodded to the captain and the doctor, then curtly at me.

"Advisor."

"Engineer," I replied.

Our commander looked left and right, frowning. "How many green guys do you think we oughta take along, this time? Just one?"

"Against regulations for first contact on a planet above tech level eight," Guts reminded him. "Sorry, sir."

Olm sighed. "Two then?" he suggested, hopefully. "Three?"

Nuts shook her head. "I gotta bad feelin' this time, Captain," she said.

Melodramatic, yes, but we've learned to pay attention to her premonitions.

"Okay, then," Captain Olm nodded. "Many. Dial 'em up, will you, Doc?"

Guts went over to a cabinet lining the far wall of the chamber, turning a knob all the way over to the last notch on a dial that said 0, 1, 2, 3, M.

(One of the most remarkable things noted by our contact team, when we first encountered Demmies, was how much they had already achieved without benefit of higher mathematics. Using clever, handmade rockets, their reckless astronauts had already reached their nearest moon. And yet, like some primitive early human tribes, they still had no word for any number higher than three! Oh, today some of the finest mathematical minds in the universe are from Dem. And yet, they cling—by almost-superstitious tradition—to a convention in daily conversation . . . that any number higher than three is—"many.")

There followed a hum and a rattling wheeze, then a panel hissed open and several impressive figures emerged from a swirling mist, all attired in lime-green jump suits. They were Demmie shaped, and possessed a Demmie's pointy teeth, but they were also powerfully muscled and tall as a human. Across their chests, in big letters, were written.

JUMS

SMET

WEMS

KWALSKI

They stepped before the captain and saluted. He, in turn, retreated a pace and curtly motioned them to step aside. One learns quickly in the service, never make a habit of standing too close to greenies.

When they moved out of the way, it brought into view a smaller figure who had been standing behind them, also dressed in lime green. Her crisp salute tugged the uniform, pulling crossed bandoliers tightly across her chest, a display which normally would have put the captain into a panting sweat, calling for someone to relieve him at the con. Here, the sight rocked him back in dismay.

"Lieutenant Gala Morell, Captain," she introduced herself. "You and your party will be safe with us on the job." Snappily, she saluted a second time and joined the others.

"Aw hell," Olm muttered to me as the security team took up stations behind us. "A girl greenie. I hate it when that happens!"

All I could do was shrug and share a brief glance with Nuts. I already agreed with her dour feeling about this mission.

The dissolution tech ushered us into position, taking any metal objects to be put in pneumatic tubes. Guts made sure, as always, that the medical kit went into the tube last, so it would be readily available upon arrival . . .

. . . a bit of mature, human-style prudence that he then proceeded to spoil by saying "Always try to slurry with a syringe on top."

"Yup." The captain nodded, perfunctorily. "In case of post-nozzle drip."

But at that moment he was more interested in guns than puns, checking to make sure that there were fresh nanos loaded in the formidable blaster at his hip.

"Ready, sir?" the tech asked through the transparent door, trying to catch my gaze even as she addressed the captain. Her nickname, "Eyes," came from big, doelike irises that she flashes whenever I look her way. She is very pretty, as Demmies go . . . and they will go all the way at the drop of a bootlace.

"Do it, do it, do it!" Olm urged, rocking from foot to foot.

She turned a switch and I felt a powerful tingling sensation.

For those of you who've never slurried, there can be no describing what it's like to have a beam zap through you, reading the position of every cell in your body. Then comes the rush of solvent fluid, flooding in through a hundred vents, filling the transport chamber, rising from your boots to your thighs to your neck faster than you can cry, "I'm melting!"

It doesn't hurt. Really. But it is disconcerting to watch your hands dissolve right in front of you. Closing your eyelids won't help much, since they go next, leaving a dreadful second or two until your entire skull—brain and all—crumbles like a sugar confection in hot water.

Ever since it was proved—maybe a century ago—that the mind exists independent from the body, philosophers have hoped to tap marvelous insights or great wisdom from the plane of pure abstraction. Some try to do this by peering into dreams. Others hope to sample the filtered essence of thought from people who are in a liquid state.

Oh, it's true that something seems to happen—thoughts flow—during that strange time when your nervous system isn't solid anymore, but a churning swirl of loose neurons and separated synapses, gurggling supersonically down a narrow pipe two hundred miles long. Giving new meaning to "brain drain."

But in my experience, these stray thoughts are seldom profound. On that particular day—as I recall—my focus was on the job. The most fundamental underpinnings of my task as Earthling Advisor.

First—above all other requirements—you have to like Demmies.

I mean really like them.

Try to imagine spending a voyage of several years crammed in tight quarters with over a hundred of the little devils, sharing constant peril while daily enduring their puckish, brilliant, idiotic, mercurial, and always astonishing natures. It would drive any normal man or woman to jibbering distraction.

Against such pressures, the human advisor aboard a Demmie ship must always display the legendary Earthling traits of calmness, reason and restraint. Plus—heaven help us—a genuine affection for the impossible creatures.

At times, this fondness is my only anchor. While I'm loyal to my Demmie captain and crewmates, there have been days when some infuriating antic leaves me frazzled to the bone. Times when I find that I can fathom the very different attitude chosen by our Spertin foes, who wish to roast every living Demmie, slowly, over a neutron star.

When such moments come, I have to take a deep breath, count to ten, and find reserves of patience deeper than a nebula. More often than not, it's worth it.

Or so one part of me told the rest of my myriad selves, during that timeless interval when I had no solid form. When "me" was many and a sense of detachment seemed to come naturally.

Which just goes to show you that it never pays to do any deep thinking when you're in a slurry.

I regained consciousness on a strange world, watching my hands reappear in front of me as the reconstructor at the Nozzle end of the Hose re-stacked my cells, one by one, in the same (more or less) relative positions they had been in before slurrying down.

Did I have that mole on my hand, before? Isn't it a lot like one I saw on the back of Olm's neck . . . ?

But no. Don't go there. Still, while dismissing that spurious thought, I resisted the urge to shake my head or shrug. Best to let ligaments and things congeal a few extra seconds, lest something jar loose and roll away.

I did shift my eyes a bit to look through a window of the Nozzle Chamber, at a patch of cloud-flecked sky. Overhead, the Hose stretched upward, cleverly rendered invisible to radar, sonar, infrared, and most visible light. (I could see it, of course. But then, Demmies are always amazed by our human ability to perceive the mystical color, "blue.")

A final word about slurrying. In its way, it is an efficient mode of transport, and I'm not complaining. Things might have been worse. I'm told that true matter teleportation—where an object is read and replicated or "beamed," atom-by-atom, instead of cell-by-cell—is a ridiculous impossibility. Quantum uncertainty and all that. Won't ever happen.

Nevertheless, there is a Demmie research center that refuses to give up on the idea . . . and Demmies never cease to surprise us.

(Impossibility be damned. I recommend secretly blowing up the place, just to be sure.)

Stumbling out of the Nozzle, we retrieved our tools from container-tubes and proceeded to look around the place. We appeared to have de-licquesced behind some boulders and shrubbery in an uncrowded portion of the park. Tall buildings could be seen jutting skyward beyond a surrounding copse of trees. Distant sounds of city traffic drifted toward us.

So far, so good. The greenies fanned out, very businesslike, covering all directions with their tidy blasters. I took out my scanner and surveyed various sensor bands.

"Life forms?" Olm said, peering around my shoulder, speaking loud enough to be heard over the traffic noise.

"Yes, Captain," I replied, patiently. "Many."

"Many," Nuts repeated, morosely.

"Many," Guts added, eyes filling with eagerness while he stroked his vivisection kit.

"Let's go see," Olm commanded, as I counted the seconds till something happened.

Something always happens.

Sure enough, at a count of eight, somebody screamed. We hurried toward the source, which turned out to be Lieutenant Morell. She panted, with one hand near her throat, pointing her blaster toward a set of bushes.

"I shot it!"

"What?" Olm demanded, shoving others aside to charge forward. "What was it?"

She came to attention. "I don't know, sir. Something was spying on us. I saw the weirdest pair of eyes. Whatever it was, I think I got it."

"Umm." I stepped forward, reluctant to point out the obvious. "Parsimony might suggest, in a calm city park, that your something just might have been . . . well . . . perhaps a local citizen?"

Lieutenant Morell gulped, looking at that moment just like a young human who had made the same nervous mistake.

"Of all the damn foolishness," Guts grumbled, hastening through the undergrowth, drawing his medical kit while I hurried after. Behind me, I heard the lieutenant sob an apology.

"There now," Captain Olm answered. "I'm sure he . . . she . . . or it is just stunned. You did use stun-setting, yes?"

"Sir!"

When I glanced back, he was leading her with one arm, his other one sliding around her shoulder. I should have known.

Guts shouted when he found our prowler. A humanoid, of course, like ninety percent of Class M sapients. The poor fellow had managed to crawl a few meters before the stun nanos got organized enough to bring him down. Now he lay sprawled on his back, spread-eagled, with his arms and legs pinned by half a million microscopic fibers to the leaf-strewn loam. He strained futilely till we emerged to surround him. Then he stared with large, dark eyes, gurgling slightly behind the nano-woven gag in his mouth.

Nanomachines are often too small to see, but those that are fired at high speed by a stun blaster can be larger than an Earthling ant. At medium range, only a dozen might hit a fleeing target, and they need several seconds to devour raw matter, duplicating into thousands, before getting to work immobilizing their quarry.

There are quicker ways of subduing someone, but none quite as safe or sure.

By now, a veritable army of little nanos swarmed over the captive, inspecting their handiwork, keeping the tiny ropes taut and jumping up and down in jubilation. Some, for lack of anything else to do, appeared to be hard at work sewing rips in the native's dark, satin-lined cloak and black, pegged pants. Others re-coifed his mussed hair.

(Just because someone is a prisoner, that doesn't mean he can't look sharp.)

Guts pushed his bio-scanner toward the humanoid, having to fight through a tangle of tiny ropes while mutturing something about how ". . . nanos are the winchers of our discontent," in a Shakespearean accent.

Enough, I thought, drawing my blaster, flicking the setting, then sighting on the victim's face. He cringed as I fired—

—a stream of tuned microwaves that turned all nano fibers into harmless gas. The gag in his mouth vanished and he gasped, then began jabbering frightfully in a tongue filled with moist sibilants.

I heard a hiss as Guts injected our captive with a hypo spray, using an orange vial marked ALIEN RELAXANT #1. The native tensed for a moment, then sagged with a sigh.

It's important for an Earthling Advisor to always inspect his ship's supply of Alien Relaxant Number One! Make sure of its purity. Very few sentient life forms have fatal allergic reactions to 100 percent distilled water. Nevertheless, most will respond quickly to being injected, as if a potent, local narcotic were suddenly flowing through their veins. Bless the placebo effect. Its near universality is among the few reassuring constants in an uncertain cosmos.

Guts gave me a sly wink. He knows what's going on, so I no longer have to mix batches of "ol' Number One" all by myself. But you can't assume a ship's doctor will understand. Call it an "ancient human recipe" until you're sure your medico can be trusted with the truth.

The native was now much calmer, prattling at a slower pace while I set up the universal translator on its tripod. Our captain dropped to one knee, preparing for that special moment when true First Contact could begin. Colored buttons flickered as the machine scanned, seeking meaning in the slur of local speech. Abruptly, all lights turned green. The translator swiveled and fired three more nanos at the native, one for each ear and another that streaked like a smart missile down his throat.

It isn't painful, but startlement made him stop and swallow in surprise.

"On behalf of the Federated Alliance of—" Captain Olm began, expansively spreading his arms. Then he frowned as the impudent creature interrupted, this time speaking aristocratically-accented Demmish.

"—don't know who you people are, or where you come from, but you must get out of the park, quickly! Don't you know it's dangerous?"

While I vaporized the rest of the stun-ropes holding him to the ground, Guts helped the poor fellow back to his feet.

I was about to resume questioning him when Nuts squeezed between us, giving me a sharp swipe of her elbow. I rubbed my ribs as she brushed leaves and sticks off the native gentleman's clothing, getting his measure with a few demure, barely noticeable gropes.

That was when the security lieutenant came with bad news.

"Captain, I'm sorry to report that Crewman Wems has disappeared."

Olm gave an exasperated sigh. "Wems, eh? Missing, you say? Well, hmm."

He glanced at the other security men. "I guess we could send Jums and Smet to look for him."

The two greenies paled, cringing backward two paces. I cleared my throat. The captain looked my way.

"No?"

"Not if you ever want to see them again, sir."

The captain may be impulsive, but he's not stupid.

"Hmm, yeah. Better save 'em for later."

He shrugged. "Okay, we all go. Form up, everybody!"

Each of us was equipped with a locator, to find the spigot in case we got separated. I tried scanning for Wems, but could pick up no sign of his signal. Either something was jamming it or he was out of range. Or the transmitter had been vaporized—and Wems along with it.

We scoured the area for the better part of an hour, while our former captive grew increasingly nervous, sucking on his lower lip and peering toward the bushes. Finally, we decided to let him choose our direction of march, flanked on one side by the captain and the other by our chief artificer, Commander-Engineer Nomlin, who gripped his arm like a tourniquet, batting her eyes so fast the wind might have mussed his hair again, if it weren't already greased back from a peaked forehead.

Aside from several teeth even more pointy than a Demmie's, our guide had pale skin that he tried to keep shaded with his cloak. Taking readings, I found that the sun did emit high ultraviolet levels. Moreover, the air was laced with industrial pollutants and signs of a degraded ozone layer—fairly typical for a world passing through its Level Eighteen crisis point. If proper relations were established, we might help the natives with such problems. Perhaps enough to make up for contacting them in the first place.

The native informed Nuts that his name was "Earl Dragonlord"—at least that is how the nano in his throat forced his vocal apparatus to pronounce it, in accented Demmish. He seemed unaware of any change in speech patterns, since other nanos in his ears retranslated the sounds back into his native tongue. From his perspective, we were all miraculously speaking the local lingo.

The master translator unit followed our party, watching out for more aliens to convert in this way. A typically Demmie solution to the inconvenience of a polyglot cosmos.

Our chief artificer swooned all over Earl, asking him what the name of that tree was, and how did he ever get such dark eyes, and how long would it take to have a local tailor make another cape just like his. Fortunately, Nuts had to pause occasionally to breathe. During one of these intermissions, Captain Olm broke in to ask about the "danger" Earl spoke of earlier.

"It's become a nightmare in our city!" he related in hushed tones, glistening eyes darting nervously. "The Licans are breaking their age-old vows. They no longer cull only the least-deserving Standards, but prey on anyone they wish! Why, they've even taken to pouncing on nomorts like you and me! Then there's the ongoing strike by the corpambulists . . ."

It sounded awfully complicated already, and we'd only gone fifty meters from the spigot. I interrupted.

"I'm sorry. Did you say—'like you and me?' What do you mean by that?"

He glanced at me, noticing my human features. "I was referring to your companions and me, of course. No offense meant. Although you are clearly a Standard, I can tell that your lineage is strong, and your bile is un-ripe. Or else, why would you mingle with these nomorts in apparent friendship? True, your kind is used to being hunted. Nevertheless, you must realize the rules are drastically changed here. Traditional restraints no longer hold in our poor city!"

I shared a glance with the captain. Clearly, the native thought we were visitors from another town, and that the Demmies were fellow "nomorts" . . . his own kind of people. Perhaps because of the similarity in dentition. In his hurry, he seemed willing to overlook our uniforms and strange tools.

The afternoon waned as our path climbed a tree-crested hill. Suddenly, spread before us, there lay the city proper . . . one of the more intriguing urban landscapes I ever saw.

Some skyscrapers towered eighty or more stories, with cantilevered decks protruding into a gathering mist. Many spires were linked together by graceful sky-bridges, arching across open space at giddy heights. Yet none of these towers compared with a distant edifice that shone through the sunset haze. A gleaming pyramidal structure whose apex glittered with jeweled light.

"Cal'mari!" Earl announced, gesturing with obvious pride toward his city.

"What?" blurted Nuts, briefly taking her hand from his arm. "You mean squid?"

"Yes . . . Squid," Earl said with sublime dignity, as the translator took its cue from Nuts, automatically replacing one word with another. Earl seemed blithely unaware that two entirely different sounds had emerged from his voicebox.

"Squid it is," Olm nodded, regarding the skyscrapers. And that was that. From now on, any Demmie, and any speech-converted local, would use that word to signify this town.

I sighed. After all, it was only a city. But several civilizations have made the mistake of declaring war on Demmies, over the insult of changing their planet's name without asking. Not that it ever did any good.

"Squid" was impressive for a pre-starflight city. At one time, it must have been even more grand. The metropolis clearly used to surround the park on all sides, though now many quarters seemed empty, devoid of life. Once-proud spires were abandoned to the ravages of time, with blank windows like blind eyes staring into space. But straight ahead, the burg still thrived—a noisy, vibrant forest of tall buildings draped in countless sheets of colored glass, resembling twentieth-century New York, dressed up with ostentatious, spiral minarets.

Skeins of filmy material, like mosquito netting, spanned the spaces between most buildings. Many windows and balconies were also covered with a gauzy, sparkling sheen—screen coverings that I later learned held bits of sharp metal or broken glass. As the sun sank, Squid resembled a maze of glittering spiderwebs, festooned with drops of dew.

Broad roadways were congested with cyclopean motor cars and lorries, all jostling for space and revving their engines before racing at top speed for an open parking space. I saw that every fourth avenue was a canal carrying boats of all description. My sinuses stung at the smell of ozone and unburnt hydrocarbons.

"Well, will you looka that!"

Our doctor pointed beyond the downtown area, to where jagged terrain rose steeply toward a rocky hill, its summit topped by striking silhouettes, totally unlike the metropolitan center. Scores of midget castles stood on those heights, with dark battlements and towers jutting from every slope. Earl Dragonlord sighed with gladness to see them, and motioned for us to follow.

"Come along, Cousins. Sunshine is bad enough, but we definitely should not be out by moonlight! At home I'll fit you with more appropriate clothes. Then we can go to the Crown."

"Uh, is that where we'll speak to your government leaders?" Captain Olm asked. "We do have work to do, y'know."

The last part was directed at Nuts. Her resumed grip on our guide's elbow might force a lesser fellow to cry uncle. Earl was clearly a man of stamina and patience, all the more alluring to a Demmie female.

"Government?" he answered. "Well, in a manner of speaking. I'll introduce you to our local council of nomort elders. Unless . . . do you actually wish to meet the mayor of Squid? A standard?" He glanced at me. "No offense."

"None taken," I assured. "Actually, I think our capt—our leader refers to government on a planetary scale. Or, in lieu of a world government, then some international mediation body."

Earl's look of puzzlement was followed by a dawning light of understanding. But before he could speak, a low groaning sound interrupted from the city, rising rapidly to become an ululating wail. Our greenies drew their weapons. Earl's dusky eyes darted nervously.

"The sunset siren! A welcome sound to our kind, in most cities. But alas, not in poor Squid. We must go!"

"Well then, lead on MacDuff," Olm said, nearly as eager to be moving along. Earl looked baffled for a moment. Then, with a swirl of his cape, he hurried east (with our ship's engineer clinging like a happy lamprey), pushing on toward the pile of gingerbread palaces that now seemed aglow against a swollen reddish sun.

"It's lay on, Captain," I muttered to Olm as we hurried along. "If you fancy quoting Shakespeare, you might try to get it right."

Lieutenant Morell chirped a giggle from her guard position, covering our rear. Olm winced, then ruefully grinned.

"As you say, Advisor. As you say."

From the park, we dropped toward a dim precinct of low dwellings that lurked between us and yonder hilltop castles. I glanced back at the downtown area, noting with surprise that the streets and canals no longer thronged with traffic. In a matter of moments they had become completely, eerily, deserted.

Dusk deepened and the largest of three moons rose in the east, about two thirds the size of Luna and almost as bright. Its phase was almost full.

In order to reach the elegant towers where Earl lived, we first had to cross a sprawling zone of dark roofs and small, overgrown lots, laid along an endless series of curvy lanes and cul-de-sacs.

"Urbs," Earl Dragonlord commented with apparent distaste.

"Hold on a minute," offered Guts, rummaging through his medical bag. "I think I've got some bicarbonate for that."

"No, no." The native grimaced. "Urbs. These are the surface dwellings where Licans make their homes for the greater part of each month, feigning to live as Standards used to, long ago, before the Great Change, in tacky private dwelling places, depressingly alike. All blissfully equipped with linoleum floors and formica countertops, with doilies on the armrests and bowling trophies on the mantelpiece. And never forget a lawn mower in the garage, along with hedge trimmer, weed-eater, automatic mulcher, leaf blower, snow blower, and razor edged pole-pruner. . . ."

Of course these terms were produced in Demmish by the translator in his throat. They might only approximate the actual meanings in Earl's mind.

"Sounds awful," Guts commiserated, patting the arm not held in a hammerlock by Nuts.

"Yes. But that is just the beginning. For under the floor of each innocent-looking house, there lurks—"

He paused as the Demmies all leaned toward him, wide-eyed.

"Yes? Yes? What lurks!?"

Earl's voice hushed.

"There lurks a trap door . . ."

"A secret entrance?" Captain Olm asked in a whisper

Our guide nodded.

". . . leading downward to catacombs below the urb. In other words, to the sub-urbs, where—"

I cut in, coughing behind my hand. I did not want my crewmates slipping into a storytelling trance right then.

"Hadn't we better move on then, while there's still light?"

Earl cast me a sour glance. "Right. Follow me this way."

Soon we passed down an avenue lined by bedraggled trees. No light shone from any of the rusty lampposts onto narrow ribbons of buckled sidewalk bordering small fenced lots. Most of the houses were dark and weedy, with broken tile roofs and missing windows, but one in four seemed well tended, with flower beds and neatly edged lawns. Dim illumination passed through drawn curtains. Once or twice, I glimpsed dark silhouettes moving within.

The Demmies, their eager imaginations stirred by Earl's testimony, kept swiveling nervously, peering into the darkness, shying away from the gaping storm drains. Our greenies, especially, looked close to panic. They kept dropping back from their scout positions, trying to get as close to the captain as possible, much to his annoyance. At one point, Olm dialed his blaster and shot Ensign Jums with a dose of itch-nanos. The poor fellow yelped and immediately ran back to position, scratching himself furiously, effectively distracted from worrying about spooks for a while.

I admired how efficiently Earl had accomplished this transformation. His uninformative hints managed to put my crewmates into a real state. I wondered—did he do it on purpose?

Almost anything can set off Demmie credulity. Once, during an uneventful voyage, I read aloud to the crew from Edgar Allan Poe's "The Telltale Heart."

Mistake! For a week thereafter, we kept getting jittery reports of thumping sounds, causing Maintenance to rip out half the ship's air ducts. The bridge weapons team vaporized nine or ten passing asteroids that they swore were "acting suspicious," and the infirmary treated dozens for stun wounds inflicted by nervous co-workers.

Actually, if truth be told, I never had a better time aboard the Clever Gamble, and neither did the Demmies. Still, Healer Paolim took me aside afterward and demanded that I never to do it again.

The urb became a maze. Few of the streets were straight, and most terminated in outrageously inconvenient dead-ends that the translator described as culled-socks—an uninviting and unappetizing name. Even in better days, it must have been a nightmare journey of many kilometers to travel between two points only a block apart.

I felt as if we had slipped into a type of warped space, like a fractal structure whose surface is small, but whose perimeter is practically infinite—a true nightmare of insane urban planning. We might march forever and never get beyond this endless tract of boxlike houses. Captain Olm shared my concern, and while the other Demmies peered wide-eyed at shadows, he kept his sidearm nonchalantly poised toward Earl's back, in case the native showed any sign of bolting.

I scanned selected dwellings with my multispec. Blurry infrared signals indicated humanoid forms within. From carbon scintillation counts, it seemed this part of city must be as old as the downtown area. I wondered about the apparent fall in population. Were things like this planetwide? Or did these symptoms relate particularly to the local crisis our guide had mentioned?

Surreptitiously, I pressed my uniform collar, turning it into a throat microphone to call the ship with an info-quest. Soon, the nanos in my ear canal whispered with the voice of Lieutenant Not'a Taken, on duty at the Clever Gamble's sensor desk.

"Planetary surface scanning underway, Advisor Montessori. Preliminary indications show that paved cities comprise over six percent of total land area, an unusually high proportion, even for a world passing through stage eighteen, though much contraction appears to have occurred recently. Gosh, I wish I was down there exploring with you guys, instead of stuck up here."

"Lieutenant Taken," I murmured firmly.

"Umm . . . survey also shows considerable environmental degradation in agricultural zones and coastal waters, with twenty-eight percent loss of topsoil accompanied by profound silting. Say, will you bring me back a souvenir? Last time you promised you'd—"

"Lieutenant—"

"All right, so you didn't exactly promise, but you didn't say 'no' either. Remember the party in hydroponics last week? You were talking about detection thresholds for supernova neutrinos, but I could tell you kept looking down my—"

"Lieutenant!"

"The worst environmental damage seems to have occurred about a century ago, with gradual reforestation now underway in temperate zones. Umm, I've just been handed a preliminary estimate of the decline in the humanoid population. Approximately sixty percent in the last century! Now that's puzzling, I see no sign of major warfare or disease. And there are some other anomalies."

"Anomalies?"

"Bio section urgently asks that you guys send up some live samples of the planet's flora and fauna. Two of every species will do, if that won't be too much trouble. Male and female, they say . . . as if a brilliant man like you would ever forget a detail like that."

Exerting patience, I sighed. Subvocalizing lowly, I repeated—

"Anomalies? What anomalies are you talking about?"

"It's got me worried. I admit it. I haven't seen you since the party. You don't answer my calls. Doctor . . . was I too forward? Why don't you come to my quarters after you get back and I'll make it up to—"

I let go of my collar. The connection broke and my ear-nanos went quiet, letting night sounds float back . . . including a faint rustling that I hadn't noticed before. A creaking . . . then a scrape that might have been leather against pavement.

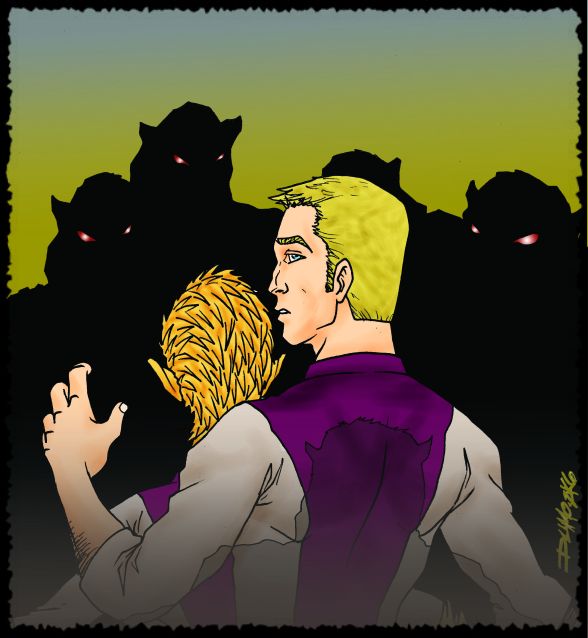

The captain halted abruptly and I collided with his back. Through his tunic I felt the tense bristles of Demmie hackle-ridges, standing on end. Olm's pompadour just reached my eyes, so I couldn't see ahead. But a glance left showed the ship's healer also stopped in his tracks, staring, utterly transfixed by something.

Lieutenant Morell hurried forward and gasped, fumbling the dial of her blaster.

A sudden, grating sound echoed behind me, followed by a clang of heavy metal on concrete.

As I rotated, a horrific howl pealed. Then another, and still more from all sides.

Before I could finish turning around, a dark, flapping shape descended over me, enveloping my face in stifling folds and choking off my scream.

David Brin is the author of many novels and short stories.