Picture a lonely human, sleeping fitfully atop a cold marble slab in an alien cemetery, his dreams threaded by a night-long rhapsody of the undead—a crooning zombie serenade.

How restful would you find that, after a long hard day getting pummeled by bourgeois werewolves, seeing your comrades snatched away by cloaked figures in the night, and then losing even the distant comfort of contact with your starship, orbiting far overhead?

Would your slumber be fitful? Disturbed?

Not mine. For the rest of that long first night on Oxytocin 41, I slept like . . . well . . . the dead . . . somehow knowing that my new friends—Moulder and Sully—would guard me until dawn. Protecting the most precious thing that I had left. Something the two of them no longer possessed.

Life.

The next morning's weather was "perfect" for my kindly hosts. Dank, chilly and overcast, but not too humid. An ideal sort of day for "recents"—the newly risen dead—to stroll into town.

We had to wait, of course, for the great Zombie Conclave to break up, after that strangely stirring nightlong dirge. The (literally) haunting harmonies at last began to fade, along with the brittle constellations, when a pale morning glow spread in the east. Gradually, through a predawn mist, shambling figures could be seen descending through the graveyard, returning to tombs and crypts, then pulling shut their hinged lids, leaving behind a trampled slope scattered with various organs, limbs and other fallen parts, twitching, dissolving into sludge and vapor.

A few of the oldest walking cadavers—nearly fleshless and evidently confused—wandered past the tombstones and monuments, moaning softly as they meandered toward the dim city skyline, heedless of a mine field that lay in the way, just short of the town wall. A staccato of muffled explosions made me wince. But Moulder, the male zoom who had befriended me last night, grunted with satisfaction each time a detonation resonated through the rows of tombs.

"That's how I plan to move on, when the time is right," he commented. "With a bang. None of that soul-o whimpering for me!"

A final coffin lid slammed shut, even as the mist condensed into swirls and then clouds that drifted upward, revealing the resplendent skyscraper towers of a city that had been named—until yesterday—Cal'mari. In this light, the metropolis looked pretty typical for a Stage Eighteen world . . . only with some unique features. For example, a maze of netting—like spiderwebs—making it next to impossible for any creature (alive or undead) to fly between most buildings. One of many defensive measures erected by the planet's living population. Perhaps paranoid . . . but understandable, given what I had learned so far.

The city proper was a realm for the planet's most numerous subspecies, known as "standards"—sufficiently humanoid that an Earthling like me could walk among them. At least that was what I hoped to do . . . with help from the substantial makeup kit that my other new friend, Sully, carried with her at all times.

"We'll have to change your skin tone and put some box-corners on your ears," she commented while applying putties and sprays "Oh! And let's give you a nice goatee beard to cover up that awful chin."

I stopped myself from blurting: "What's wrong with my chin?" Even with nano translators tuned to the local language, I had to assume there would be, well, exaggerations. So I quashed any impulse to take offense.

Besides, she had a gentle touch . . . and was by far the most attractive corpse I had ever met.

Sully even made a few alterations to my Alliance uniform, sewing some of the rips and tears from my battle with local lycanthropes, the night before, then adding a few clever touches to make my clothes resemble normal street attire. Moulder, pacing nearby, grumbled that she was putting in far too much effort.

"It's not as if he'll really blend in. Have you forgotten we'll be with him?"

Moulder had just finished puttying his own face, but only in a very dark room would anybody fail to note a missing chunk of skull, perhaps the very injury that brought him to this place. To his second phase of "life."

"Oh, hush," Sully responded. "Don't you want the flavor of a good deed to carry with you, as memory and mind fade away?"

Moulder muttered some more. But of course, this merely confirmed something that I've long observed during my voyages aboard the Clever Gamble. For all of its apparent malignity, the universe also overflows with kindness and skill.

Anyway, I just have to believe it. A character flaw, I suppose. They only pick optimists to serve as human advisors aboard Demmie-crewed ships.

Anyone else would probably go quite insane.

Our day began with a hurried search of the big park where my crewmates and I had slurried down to this planet, only a day before. I held out little hope of finding the Nozzle intact. After all, I couldn't see the Hose. A careful scan of the sky showed no blue, shimmering line leading upward to the heavens. Still, I had to check. If our ship had been destroyed, the Nozzle-reconstructor should still be there . . . along with a tangled coil of fallen tubing that would trail ever westward, falling from space to snarl trees, power cables, and clotheslines across half a continent.

The Nozzle was gone. No sign of it in the park. And, in a sense, that was encouraging! So, the Gamble hadn't been destroyed in a flash. There must have been time to at least begin hauling in the slurry hose.

A small comfort. Very small.

Our search brought forth one more clue . . . a tattered tunic of lime green, very large, with WEMS spelled across the chest. I turned it over carefully, checking for clues to what might have become of the security crewman, but there were none that I could see.

Then I tried using the garment's built-in transmitter to contact Commander Talon, on the Clever Gamble.

No luck. My ear nanos conveyed only space static.

Something terrible must have happened to the ship. Because my crewmates would never leave comrades stranded below for so long. Say what you will about Demmies; but most of them are loyal to a fault.

I've got to find out what's going on!

No choice then, but to head into the town proper, accompanied by Moulder and Sully. In order to seek aid from one of the local dignitaries.

The apparently renowned "Professor Ping."

I had to revise my earlier notion about social arrangements in the city that only yesterday (without the inhabitants' permission or knowledge) was renamed "Squid." So far, I had encountered four subspecies of humanoids on this world, comingling in a complex life cycle, with some of them treating others as prey. A place where—as I've said—paranoia seemed quite justified.

Nevertheless, the various types weren't at war. Not exactly.

True, the city showed signs, everywhere, of profound efforts at self-defense. Like those huge, ominous nets, spanning open spaces. High concrete walls, topped with razor wire, ran along the river bank, dividing downtown from the park/cemetery area, turning the broad stream into a moat. Watchtowers overlooked several gated bridges.

Yet, despite the backdrop of predation and mutual mayhem, it was remarkably easy to enter the city proper. No one stopped us, or even scrutinized passersby, as we ambled across one of the spans into the main commercial zone. At the city end, formidable barriers had swung aside on hinges, apparently unneeded by daylight. Motor traffic rushed past us in both directions.

I wondered—could the local interspecies asperity be limited only to night? Was it simply a matter of bad luck (and Demmie impatience) that Captain Olm had us slurry down to this metropolis so late in the day?

Standards swarmed the streets and canals of Squid City, busy at trades and industry. Making, buying and selling things. Bickering, talking, raising their young. Doing all the normal things of civilization. Yet, amid the throng I also glimpsed a few of the predatory types—always given plenty of room by the standards, who stepped aside out of reflex. As if the protection of daylight could only be trusted so far.

A lordly nomort strode past one side street, smiling nonchalantly—and frighteningly—with sharp, Demmie-like teeth, his aristocratic black cloak drawn up into a hood, for protection from the sun. Later, we turned a corner and almost ran into a pair of hirsute licans, with trails of drool dangling from their lower tusks. I cringed for an instant, fearing that the larger one might be Besh, the wolfish leader of a band that had imprisoned and beaten me in the urb.

But no, unlike Besh, these two were well-groomed. In fact, their combed and coifed facial fur was perfect. As we passed, I overheard a snatch of raspy speech. It was only a moment, but they seemed to be in heated discussion of some kind of sporting event. Almost like a couple of regular guys on a street, back home.

Apparently, on Oxytocin, death wasn't like the sudden, on-off transition back on Earth, or that I had seen on so countless other worlds—an either-or thing. Till now, I simply assumed it was a law of nature. Only here, "life" had stages, complex, unpredictable, filled with change and nuance.

Moreover, evidently some kinds of afterlife rated higher than others. While the rare nomorts moved through town like aloof nobility, and licans had the apparent tastes and temperaments of middle class monsters, clearly the poor zooms got no more respect than that accorded to ghoulish proletarians. Though my two lifeless friends had made great efforts to fit in—with all that putty and lacquer—they got only curt and disdainful looks from citizens in prim, high-collared business suits hurrying by on their way to work. Standing at a curb, waiting for the light to change, Moulder seemed especially unpopular. Normal folk edged away, pinching their noses.

I soon learned more about this prejudice, when Sully asked if I was hungry.

"Starving!" I replied. "I suppose when we get to Professor Ping's . . ."

She shook her head—carefully of course.

"The Prof is absentminded. He may not have stocked up for himself, let alone a guest. We should bring something."

She gestured to an establishment on a commercial street . . . a grocery store apparently, with commodities stacked on shelves—bottles, boxes and cans, mostly.

"I prefer to shop at Wail Mart," Moulder commented. "Half of their employees already have one foot in the—"

"That's at the other end of town," Sully interrupted. "And we should hurry along."

Now I caught scents that churned my stomach with hunger pangs. Normal landing party procedure calls for detailed tests before consuming local food on an alien world. But right then, possible allergic reactions seemed the last of my worries.

"I'm afraid I haven't any money."

"That's okay," Sully assured. "I had savings when I died, and no heirs but a brother, who insisted I take it with me. Fat lot of good it'll do me soon. So take this." She held out a purse. I heard clattering nonmetallic coins. "Anyway, you must do the buying for us."

"Why's that?"

She pointed. A man wearing a stained apron stood in the doorway, glowering at our little group. To his right, set prominently in the window, stood a sign which nanos in my eyes set to work translating, overlaying the alien typescript with Demmie letters, that seemed to hang ghostly in space, before me—

NO SHOES? NO SHIRT? NO PULSE?

NO SERVICE!

LYCANS SERVED UNTIL NOON ONLY.

(NO EATING, DRINKING, OR HOWLING ON PREMISES.)

NOMORTS STRICTLY CASH. (NO B-BANK DRAFTS.)

WE GLADLY ACCEPT CAL'MARI EXPRESS.

Underneath, a second, smaller sign bore a caricature of a zombie with one eyeball hanging out of a socket and both disjointed arms outstretched before it. Jagged slash marks across the figure translated as FORBIDDEN, while a slogan advertised—

THIS ESTABLISHMENT PROTECTED AND SANITIZED BY ACE CREMATION SERVICE.

Sully must have sensed my outrage. She put a hand on my sleeve, speaking in a low voice.

"Don't make a fuss."

"But it's . . ."

I kind of strangled in my search for the right words. Not "racist" or "sexist," certainly . . . or even "speciesist."

Life-Chauvinism, was all that came to mind. An irrational and bigoted preference for the animate over the rotting-deceased. How unevolved.

"Never mind," she urged, slipping me a tattered sheet of paper. "Just get the things on this list, will you? We'll wait around the corner, in that alley over there." She gave me a pretty smile (that must have been lethal, when she was alive) and Moulder stuck up his remaining thumb in a friendly gesture as they both turned to go.

The proprietor sent me a sour look as I entered the store with list in hand. I felt certain there must be a word in their language for my kind—the sort who fraternizes with pariahs—and I guess I shouldn't have been surprised. In both Earth and Demmie history there were plenty of shameful periods when fear conjured odious, illogical prejudices. Level Eighteen worlds often had plenty.

In the overall context of time, it could be viewed as just another, natural phase along this planet's hard road to maturation.

Natural or not, I hated it.

I mentioned that the clothing fashion among standards ran toward bulky, pseudo-Victorian attire, with high necklines for both men and women. The store offered an assortment of what at I took for pet collars—studded with sharp spikes—till I saw a sign: "FOR A RESTFUL NIGHT'S SLEEP." It made me wonder what they used as pillows here.

The shopping list was fairly easy to follow. Eye nanos scanned my field of view as I looked around the store, highlighting matches with the letters on Sully's paper. For example, I quickly found SlimFaust—the liquid soul food. Also into the basket went vials of cosmetics and preservatives, like those she used that morning.

For myself, I chose the blandest of food products. A loaf of plain brown bread and some yellow fruits, like bananas, that smelled pretty good. My hand hovered near a box of breakfast cereal. The illustration looked cheery enough at first, featuring ravenous kids surrounding a giant bowl full of what looked like . . . grinning Viking heads.

Canutes n' Berries

It's grendelicious!

Eat it slow or beowulf it down!

I vowed to have a talk with whoever programmed my nano-translators. If I ever made it home.

On impulse, I threw in a cheap brown jacket and one of the doggie collars. I'd surely be able to repay Sully. If not when we reached Professor Ping, then upon being reunited with the Clever Gamble. Perhaps Commander-Healer Paolim could even do something about the condition Sully and her friend were in—though I could hardly imagine how.

A clump of manicolored plastic coins fell on the counter from her handbag, when it came time to pay. While picking through the grimy pile, the clerk looked at me with disgust, as if to say "Are you sure you have a pulse?" I'm all but certain he shortchanged me. But how could I protest? I didn't know the local coinage and he'd have me dead to rights.

Taking up the bag of purchases, I left the store and turned right, seeking the alley where Sully and Moulder said they'd await me. I reached the corner, holding out her list. "I hope this is everything you wanted—"

Staring, I realized that my two dear-departed friends were gone.

In their place stood a lanky man wearing what looked a lot like a trenchcoat and battered fedora. Poking around, he used the toe of one shoe to nudge something small and smoldering . . . perhaps a bit that had fallen off of Moulder. It didn't take Demmie instincts to know a cop when I saw one.

Shall I just step forward and introduce myself? Work my way up the ladder of officialdom? Take me to your leader?

As the fellow bent over to examine the site closer, his coat parted, revealing a vicious-looking gun strapped to one thigh—almost certainly not set to stun. Holstered alongside were several wooden stakes. And a hammer.

Maybe the authorities aren't my best option, right now, I pondered, and started to back away . . .

. . . only to collide with a wall that hadn't been there a second ago. I turned swiftly, to find myself looking up at a formidable figure dressed in police blue. Shiny buttons spanned a chest that seemed almost as broad as the alley. But that was not the biggest surprise.

The face grinning down at me was suddenly familiar.

"Uh . . . Crewman . . . Wems?"

The Demmie security man kept smiling, but something struck me as wrong. Not the layer of makeup that gave his face (like mine) an imitation local-greenish tone. No, it was the teeth. Several were crudely capped, I realized suddenly, in order to make them look less pointy.

"Hello Professor," Wems said in a low and friendly tone.

That is, it seemed friendly . . . till he whipped forth a truncheon, the size of a tree branch, and used it to rap me sharply on the head, ending that brief morning and bringing back the night.

After it has happened to you enough times—(and if you hang around Demmies, it will)—you finally get of kind of used to waking up in strange, dank places with a splitting headache, lacking a clue to where you are and how you got there.

(There was that time when Captain Olm insisted that we go bar-hopping on Eurythromycin-Six . . . and we came to in the harem of a Slug Queen on Escargotia, more than ninety parsecs away. But that's another story.)

On this occasion, at least, I regained consciousness on a soft surface. Not a bed, exactly, but a cushioned pallet or sofa, in a dim room that was illuminated only by a single, fancy candelabra on a nearby table. Dust motes and the flickering light made my eyes itch, so I quickly looked away from the flames, rubbing my nose. But the rest of the chamber wasn't any more comforting. Cobwebs spanned the corners and furnishings. Gloomy figures, attired in lavish native costumes, stared down at me from large portraits, with expressions that seemed to say nothing good will come of this.

I sat up, gingerly bracing for the inevitable stabs of pain. At least Wems had been trained well, there was that small mercy. His application of force had taken away consciousness without crushing my skull. Even the hematoma, throbbing under my fingertips, didn't seem too blood-sodden or swollen. A fine, professional job. Only . . .

. . . only why?

Why did Wems disguise himself as a local constable and then attack me?

Wincing as I stood up, I inspected my own body and then my surroundings. Both seemed similarly shoddy, creaky and derelict, having seen better days. The furniture and decorations looked as if they must have once been plush and upscale, though numerous gashes and gouges now defaced the wood paneling and several paintings—perhaps traces of some long-ago battle that once careened through these chambers. Dark, unpleasant-looking stains blemished several patches of wall and floor.

I wasn't especially surprised, upon trying the door, to find that the knob would not turn. It was locked from the other side. Moreover, the portal was too heavy and stout to force, even with human muscles.

On the table, next to the candelabra, I did find a surprise. The shopping bag that I had been carrying when Wems knocked me out. Next to it were several of my purchases . . . the loaf of bread, the bundle of fruits. Then I noticed symbols, written in the thick dust. Next to the bread, some finger had traced a Demmie-script glyph for safe. On the other hand, the fruit that had smelled so fine came accompanied by a mark that stood for hallucinogen. (A much-too common and familiar emblem; Demmies had never been shy about been experimentation. Especially before human beings arrived, giving them an attractive alternative—the power to meddle on an interstellar scale.)

Nearby lay a tall and elegant (though chipped) carafe of water, plus an empty packet from one of our Alliance food-testing kits. So, Wems had cared enough to give me a choice. To not trust him and starve. To trust and eat something blandly nourishing. Or to seek escape down paths of illusion.

I picked up one of the yellow, bananalike orbs. It sure smelled good. And escape did have its attractions.

But frankly, I wasn't tempted. Illusion is overrated. Anyway, this adventure was already stretching credulity. Bread and water would help anchor me down.

They also stanched the agony of hunger and thirst. I've had better meals. And much worse.

Thank you, Wems. I'll be sure to mention this at your court-martial.

Energy restored, I began turning my thoughts to escape, starting with a thorough thumping of the walls. After all, this was just the sort of place to have hidden panels leading to secret passageways, right?

No luck with the first wall. But, pushing aside a set of heavy curtains, I did discover a set of double doors with cracked glass panes. Unlike the other portal, this one was unlocked. In fact, it gaped open to a wide, stone balcony. And beyond that, a nighttime cityscape.

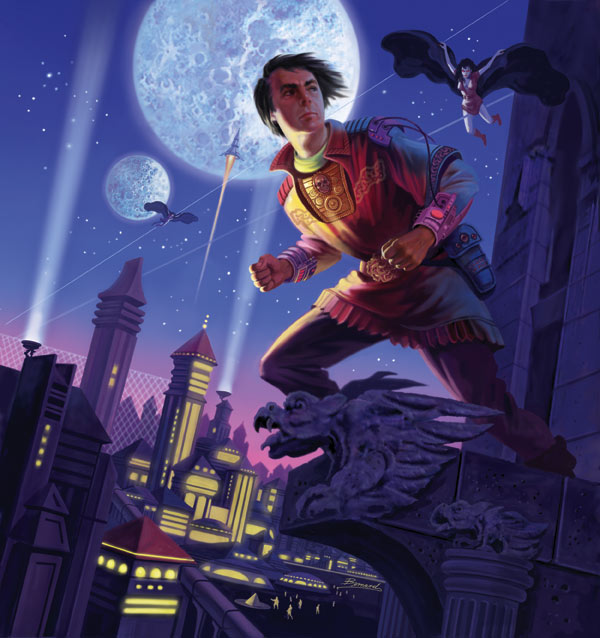

Stepping outside I found the lights of Squid spread out before me, a forest of glittering towers, their twinkles gradually merging into a scattering of stars and nebulae above. Taking a deep breath and standing quite still, I gazed skyward for a time. Although the constellations were alien, I still felt homesick just looking at them. All I could do was cast my hopes and thoughts toward my ship and crewmates, who might be struggling with danger even now. The other thought . . . that it might already be too late . . . was unbearable. That the Clever Gamble and her stalwart company might already be destroyed, stranding me forever on this lonely and desperately strange world.

My balcony-perch jutted near the top of a tall masonry building—at least twenty stories high—built in a rather gothic style. Peering left and right, I saw no easy route to get away. No nearby verandahs lay within reach through some cinematic leap . . . though I did spot a collection of garish gargoyles, spaced around the cornice-ledge, that seemed to leer and taunt, as if daring me to use their crumbling shapes for hand and foot holds.

I didn't feel that desperate. Not quite. Not yet.

Some of the closest buildings loomed even taller than this one. Generally, the higher floors were dark and perhaps long abandoned; but many of the windows lower down shone with light. Dim figures could at times be glimpsed, passing back and forth beyond closed curtains. Despite the warm evening, not a single window or door was open.

Except . . . for . . . this one, I realized.

Peering about, I found that I could trace patterns of netting that I had seen earlier, spanning the open space between many structures . . . an array of obstacles that had seemed formidable by day, and all-too evanescent by the wan glitter of starlight. Moreover, the defensive shroud looked rather sparse near me.

In fact, I seemed to be situated well above all but a few of the webs.

Checking the balustrade and nearby wall, I finally found one attachment point, just overhead, near the right-end of the balcony. From a gobbet of sticky substance, a slender filament plunged arrow-straight into the darkness, parallel to the ground. If the cord was meant to support netting, those mesh strands had long vanished.

In fact, I began to suspect that was never its purpose. Tentatively and more than a little nervously, I reached out and touched the threadlike cable.

It hummed. A vibration that at once reminded me of the music from that cemetery serenade, a night (or two?) before, in the crypt-suburb of the zombie clan. Similar to that music, and yet somehow more frightening.

Something about it made my heart race faster.

I let go and started backing away, eyes anxiously darting across the night. Maybe I should close, lock, and barricade the balcony doors. After all, by day I would have many options. I could even drop messages to the street below. Attract attention to my high-elevation prison. Whatever faults the authorities might have, at least they were standard humanoids . . .

I stopped, frozen in my tracks by . . .

. . . by a slight variation in the blackness out there. In the same direction as that narrow strand. Staring hard only made it go away, so I averted my gaze slightly, favoring the more light-sensitive retinal rods—an old astronomer's trick.

It returned. An inky fluttering, like a raven flapping against a sable curtain or the dark wall of an unlit cave. The tenebrous shape grew larger, closer with a suddenness that left me stunned, unable to react . . .

. . . until—quite suddenly—it arrived, impending over the balcony's stone railing with a final leap.

Landing in a graceful crouch, the manlike figure, dressed all in black, stood up slowly now, lowering both arms to gather-in the winglike folds of a large cape, before rising, straightening.

I managed to retreat a step, another. Put my hand upon the edge of the door. Preparing to slam it shut . . .

. . . when something transfixed me, preventing further motion as the dark figure finally turned to face me. The emotion of surprise.

"L-lieutenant? Lieutenant Morell?"

The face was certainly that of our security officer, the one who had accompanied the captain and me, along with the rest of the landing party, when we slurried to the planet's surface. Now dressed in local costume—nicely cut for her generous figure—she appeared to know me and started to smile with those charmingly dainty-pointy Demmie teeth . . .

. . . only no longer quite so charming. Two of them, canines at the corners of her mouth, now seemed much larger and far more intimidating. In what little light reached them from the candelabra inside, from the city, from the stars, they gleamed.

Also gleaming, almost with a light of its own, the twin-lobed décolletage of her black, low-cut attire, enhanced by a tight, push-up effect. Apparently, becoming a nomort did not alter one aspect of Demmie nature. If you got it, flaunt it.

"Hello Dr. Montessori." Her voice was familiar, even friendly, though now with a mellifluous tone, far more confident. In fact, one that I could only interpret as somehow smugly superior. Like a student who had become teacher. A long-resentful underling, now become master.

"Are you surprised to see me?"

We humans who work close to Demmies like to encourage some of their myths about the Ancient Ones, especially the widespread notion that Earthlings do not lie. Of course it isn't true. Some of our less honest ancestors used to do it monthly, even weekly, I hear.

"Surprised, Lieutenant? Not for an instant. In fact, I was expecting you. I see the transformation was effective. How do you like it?"

"I . . ." She blinked and seemed briefly nonplused. "It takes some getting used to. But how did you . . ."

Morell's expression narrowed, taking on a look of fierce calculation—in my view a less-savory substitution for the fetchingly innocent intelligence of the young Demmie officer I knew before. A feral light seemed to glow in her eyes.

"Perhaps it is time for you to find out for yourself, Professor," she murmured smoothly, taking a step forward. And I realized that the "glow" in her eyes had become something more than metaphorical.

"That is, if you are one of the lucky ones."

"L-lucky ones?" I could no longer put up a pretense of confidence. The shine had taken on a hypnotic quality, twin glints of painful sharpness that stabbed from her eyes to mine, slowing time to such a degree that my muscles felt kilometers away. Frantically ordering them to move, to slam the door between us, felt like sending messages through molasses. Her languid, poised approach would reach me long before they obeyed.

"About one in a hundred. That's the ratio among the local humanoids, Professor. The fraction of victims who then rise up all the way to become nomorts, instead of entering some lesser afterlife. Of course we don't yet know the ratio among Demmies . . . or humans . . . But I hope you do make it. I always liked you, Dr. Montessori."

It did little good struggling to avoid her captivating gaze. The sharp, hypnotic glare hurt . . . and worse . . . it itched, tickling and scraping my sinuses. And yet, at the same time, something compelling and attractive about it, felt . . . terribly familiar. Though I could not close them, my own eyes squinted.

"The captain . . ." I managed to blurt. "The others . . ."

"Everybody has a destiny, as you'll soon discover, Doctor." Her voice was smoother now, almost soothing. "It's time to feed your legendary curiosity . . . while you feed me. . . ."

Leaning forward and spreading her cape again, she opened her mouth. Those pointy canines shone. I could not move or speak.

But I did remember, all of a sudden, what was familiar about the sensation. That tickling itch. And with realization, I abruptly stopped trying to look away from her eyes. Instead, I focused all of my attention upon them, letting the force of those rays enter completely.

I gasped inward, sharply, squinted even more . . .

. . . and released an explosive sneeze.

There have been many attempts to divide the natural Terran species of Homo sapiens into subgroups. Into races. Blood types. The two (or more) sexes. All sorts of oversimplifications and outright bigotries abounded, during our crude and simpleminded climb toward civilization. Especially during phases fifteen to twenty.

And yet, one stark division was seldom mentioned, though it pervaded all times and cultures.

There had always been those who—when they felt a sneeze impending—would look for a sharp light, to help trigger it.

And then there were all the others, the rest of humanity, who thought that the first group were liars.

It wasn't till we finally arrived at level twenty, that some grasped the reason for it all.

The vampire reacted, at first, with a backward leap. A look of shocked surprise mixed with disgust.

Well, after all, her mouth had been open, taking the full brunt. Expressing some vestige of her former, mortal fastidiousness, Lieutenant Morell's expression was one of offended revulsion, even though she had been preparing to suck out my life's blood.

That countenance shifted rapidly, though, even as I blinked hard, shaking off her predatory trance. The Demmie nomort coughed, spat . . . and then snarled.

"Very clever, Professor. But that only bought you a few seconds to—"

Morell stopped. A growing look of puzzlement spread across her aristocratic nomort features.

Then, the former Demmie officer screamed.

She did more than scream. She clawed at her throat, at her shoulders and chest, nails dragging deep grooves that would have bled, if she still had a beating heart. Thrashing and shrieking, she plunged about the balcony, striking a wall, shattering a pane of the glass doors, then colliding with the nearby stone railing. Teetering dangerously, she clutched at a leering gargoyle, that first took her weight . . . and then betrayed it, toppling her over the precipice with a final screech as she plummeted into empty space.

Still sluggish, I was unable to reach the edge in time to follow Morell's plunge, though her wail reverberated through the urban canyonscape By the time I was able to look, she had vanished into the gloom below—whether caught by some net, splatted on pavement, or else grabbing some last-moment escape, I had no way to tell.

Damn, I really wanted to ask her about the others . . . about Guts and Nuts and Captain Olm.

About a strange life cycle that includes the parasitic undead.

Or if she knew anything about the fate of the Clever Gamble . . . or what any of this had to do with Crewman Wems.

Now? I would have to start investigating for myself. Only this time, I was determined not to be sidetracked by anything!

There only seemed to be one way out of here, a desperate and dangerous path, retracing the nomort's route in getting here. Cautiously, I reached out and tested the slender cable that Morell had used as a highway through the sky to reach my balcony.

Plucking it just once released a sudden throbbing pulse. A palpable wave of sound in the form of a clear harmonic chord!

Now I understood, at last, why it had seemed to be musically vibrating earlier!

Acoustically oriented active fiber. It absorbs energy if you ride it along a downward slant, turning most of your falling energy into stored sound waves. Cached energy that you can later recover, sending you back uphill the way you came.

No wonder the population of standards feared flying predators. In a way, this sonic dive-in was more impressive than any mythology of vampires transforming into bats. Though . . . now that I thought about it, there could be easy technological countermeasures, if only the standards knew about them.

Hurrying into the shabby room, I grabbed the candelabra and brought it outside, then stripped to the waist, removing my Alliance uniform tunic. Some of the woven-in circuits were torn and ruined, but many individual thread assemblies were intact. I removed one of the communications strips and chewed on the end to create a frayed contact-antenna that I then applied to the cable. With a little tinkering, I was able to create a probe that measured and tapped the stored sound . . .

. . . and rocked back from a veritable cacphony! A powerful and complex melange of wave forms that swarmed and enveloped me till I felt wrapped in sound, like some kind of pod person. It took some effort to rip away.

Hurrying back inside, I worked on the Squidish leather jacket and protective "dog collar" I had bought earlier, creating a harness of sorts. One that could ride along the cable, if only I found the trigger codes. My guess was that it would take some combination of tone and rhythm to activate a traveling wave, something with the right phase and group velocity combinations to propel me up-and-out, along the slight incline . . . toward wherever Morell came from. . . .

I avoided thinking about that while making final preparations. The important thing was that I was being dynamic again. Assertive. Whoever or whatever I found at the other side, they might be taken by surprise. And if they were nomorts? Well, maybe, with any luck, I might have another special sneeze or two inside me.

Soon the contraption was finished. I fastened it to the cable, slid my arms inside and made sure several of the leather garment's buttons were secure. Ready to go.

Indeed. I whispered urgently. "Go!"

But the tether only vibrated a little.

Well that wasn't much of a trigger. Probably needed more tonality.

Making sure of the electro-sonic connection and pressing my throat mike close, I tried to hum an even note.

The cable shuddered in response. I hummed louder . . . then much louder, but that made no difference. So, volume wasn't the key . . .

. . . nor was simply changing pitch. I had to stimulate self-amplifying wave forms. That would take complexity.

So I started to sing.

This didn't work when you tried it with the Licans, Lorg and Besh, I pondered glumly. What makes you think—

The strand started throbbing, then oscillating with chaotic ripples. Hmm. I must be on the right track.

I commenced a sample-medley, starting with opera, then working my way to bawdy ballads, to jazz riffs, to Orc-n-Roll, all of them eliciting various shakes and chaotic shudders that I took as rejection. Even displeasure. Once, the cable jerked violently and I found myself suddenly cast out, ten meters or so beyond the balcony, grimacing with a sharp pain in one shin from striking the stone railing along the way. Looking back, I saw the gargoyles grinning at me. Beyond them, through the open doors, one of those old, painted figures seemed to chide:

See? I told you so.

But I was learning. Evidently, the cord wanted something gentler, more melodic . . . maybe even nostalgic.

A little Streisand? I cleared my throat and tried belting some Babs.

That seemed almost to do the trick. "Memories" triggered a clear response! A throbbing pulse that carried me forward at least a dozen meters before petering out, though apparently still unsatisfied.

Hanging there in midair, vocalizing olde standards to charm a persnickety sonic serpent while my feet dangled above the squalid streets of Squid, I suddenly felt foolish as never before . . . (and you get plenty of opportunities when you work with Demmies.) Was it a last vestige of dignity that made me taper off and go silent, at last?

Foolish, yes. And yet, my situation also felt somewhat poignant and . . . well . . . hilarious. I had to chuckle at the absurdity of this predicament. In fact, it reminded me of the sort of thing you might see in some old-time comedic movie, from the days of flat-screen classics. Laurel and Hardy. The Stooges? No, a bit drier than that. Maybe something like Hope and Crosby.

I could tell my subconscious was busy. Connecting dots. At times like this, I knew better than to interfere.

Unleash. Let it flow.

Bob Hope, Bing Crosby . . . and Dorothy Lamour. They did all those "Road" Pictures together. The Road to Hong Kong, The Road to Morocco . . . and what was that unfinished film they hid away? It never got released till a hundred years had passed.

A weird thing. Ahead of its time. Oh yeah.

The Road To Transylvania.

No wonder it came to mind. All about darkly funny—but risque—adventures with Count Dracula and Wolfman and Duchess Sucubus . . .

I had to laugh, recalling that old treat. And yet, at the same time, I flashed on the more terrifying image of Lieutenant Morell, "vamping" me with her cleavage while preparing to drain me with those garish, deadly teeth.

Suddenly, I remembered. The theme song from that movie, a variation on their old standard. And one of the reasons that Road To Transylvania was banned, left unfinished, and hidden away, never to be seen till humanity reached another stage.

I cleared my throat . . . then started humming—

—and the sonic cord responded! First rippling nearby and then vibrating along its length, reacting to my voice by gradually unleashing pent-up energy. Wave-fringes crisscrossed, interfering and reinforcing . . . until a stable bulge formed, right behind me . . .

. . . a bulge that began pushing me forward, like some compliant sea creature. Gradually, but smoothly and without a hiccup, I began a long, steady glide into the night.

All right!

Only the pace stayed much too slow, no matter how loudly or forcefully I hummed the old melody. Evidently, the greedy cable wanted more.

So I added words, the ones that Crosby and Hope sang to Lamour. A crooning lament of fond—if kinky—recollection.

"Fangs . . . for the mammaries. . . ."

I cannot claim that I remembered them all correctly. The lyrics. It was, after all, an off-color and low-brow little ditty about three bosom buddies, trying to transcend dental jeopardies. But if I faked any stanzas, the finicky cable didn't seem to mind. Thrumming like a happy banjo string, it responded by launching me ever-faster across a dark cityscape, accelerating over the rooftops of a frightened populace who must have heard my poor ululation and doubtless thought me yet another terrifying predator. Another singing monster who, they hoped would pass them by.

Sleep tight, I thought, while crooning and zooming under the stars, toward where I knew not. It's only me, an Ancient One, but as mortal as you are.

And yet, I knew better. For history teaches a lesson, known by every other species on Old Earth.

Beware angering humans. Even those who are patient and grown up.

Especially that kind.

My destination loomed ahead. Something dark that squatted, big and formidable on the horizon, in front of a bright nebula. It would almost certainly be someplace desperately dangerous.

Only, for a moment, whatever lay in the foreground did not seem to matter much to me. Instead, my attention plunged beyond, to that milky, galactic vista, a vast nursing-ground of stars that—I knew—sang melodies far more imposing, yet more subtle and sustaining, than could ever be grasped by the unweaned planet-bound.

TO BE CONTINUED

David Brin is the author of many novels and short stories.