"Old man, old man, do you tinker?"

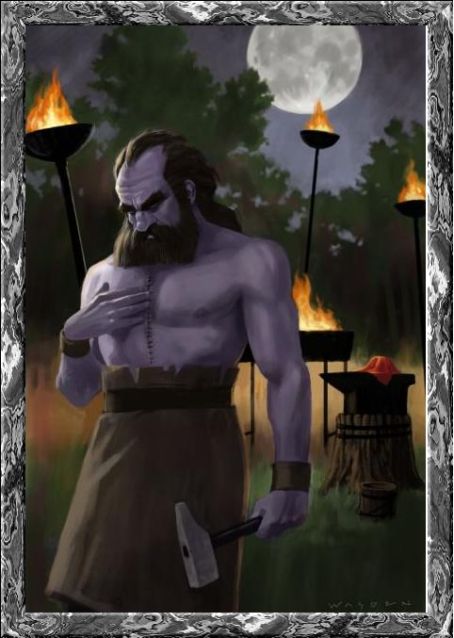

Weyland Smith raised up his head from his anvil, the heat rolling beads of sweat across his face and his sparsely forested scalp, but he never stopped swinging his hammer. The ropy muscles of his chest knotted and released with every blow, and the clamor of steel on steel echoed from the trees. The hammer looked to weigh as much as the smith, but he handled it like a bit of cork on a twig. He worked in a glade, out of doors, by a deep cold well, just right for quenching and full of magic fish. Whoever had spoken was still under the shade of the trees, only a shadow to one who squinted through the glare of the sun.

"Happen I'm a blacksmith, miss," he said.

As if he could be anything else, in his leather apron, sweating over forge and anvil in the noonday sun, limping on a lamed leg.

"Do you take mending, old man?" she asked, stepping forth into the light.

He thought the girl might be pretty enough in a country manner, her features a plump-cheeked outline under the black silk veil pinned to the corners of her hat. Not a patch on his own long-lost swan-maiden Olrun, though Olrun had left him after seven years to go with her two sisters, and his two brothers had gone with them as well, leaving Weyland alone.

But Weyland kept her ring and with it her promise. And for seven times seven years to the seventh times, he'd kept it, seduced it back when it was stolen away, held it to his heart in fair weather and foul. Olrun's promise-ring. Olrun's promise to return.

Olrun who had been fair as ice, with shoulders like a blacksmith, shoulders like a giantess.

This girl could not be less like her. Her hair was black and it wasn't pinned, all those gleaming curls a-tumble across the shoulders of a dress that matched her hair and veil and hat. A little linen sack in her left hand was just the natural color, and something in it chimed when she shifted. Something not too big. He heard it despite the tolling of the hammer that never stopped.

"I'll do what I'm paid to." He let his hammer rest, and shifted his grip on the tongs. His wife's ring slid on its chain around his neck, catching on chest hair. He couldn't wear it on his hand when he hammered. "And if'n 'tis mending I'm paid for, I'll mend what's flawed."

She came across the knotty turf in little quick steps like a hobbled horse—as if it was her lamed, and not him—and while he turned to thrust the bent metal that would soon be a steel horse-collar into the coals again she passed her hand over his bench beside the anvil.

He couldn't release the bellows until the coals glowed red as currant jelly, but there was a clink and when her hand withdrew it left behind two golden coins. Two coins for two hands, for two pockets, for two eyes.

Wiping his hands on his matted beard, he turned from the forge, then lifted a coin to his mouth. It dented under his teeth, and he weighed its heaviness in his hand. "A lot for a bit of tinkering."

"Worth it if you get it done," she said, and upended her sack upon his bench.

A dozen or so curved transparent shards tumbled red as forge-coals into the hot noon light, jingling and tinkling. Gingerly, he reached out and prodded one with a forefinger, surprised by the warmth.

"My heart," the woman said. "'Tis broken. Fix it for me."

He drew his hand back. "I don't know nowt about women's hearts, broken or t'otherwise."

"You're the Weyland Smith, aren't you?"

"Aye, miss." The collar would need more heating. He turned away, to pump the bellows again.

"You took my gold." She planted her fists on her hips. "You can't refuse a task, Weyland Smith. Once you've taken money for it. It's your geas."

"Keep tha coin," he said, and pushed them at her with a fingertip. "I'm a smith. Not never a matchmaker, nor a glassblower."

"They say you made jewels from dead men's eyes, once. And it was a blacksmith broke my heart. It's only right one should mend it, too."

He leaned on the bellows, pumping hard.

She turned away, in a whisper of black satin as her skirts swung heavy by her shoes. "You took my coin," she said, before she walked back into the shadows. "So fix my heart."

Firstly, he began with a crucible, and heating the shards in his forge. The heart melted, all right, though hotter than he would have guessed. He scooped the glass on a bit of rod stock and rolled it on his anvil, then scraped the gather off with a flat-edged blade and shaped it into a smooth ruby-bright oval the size of his fist.

The heart crazed as it cooled. It fell to pieces when he touched it with his glove, and he was left with only a mound of shivered glass.

That was unfortunate. There had been the chance that the geas would grant some mysterious assistance, that he would guess correctly and whatever he tried first would work. An off chance, but stranger things happened with magic and his magic was making.

Not this time. Whether it was because he was a blacksmith and not a matchmaker or because he was a blacksmith and not a glassblower, he was not sure. But hearts, glass hearts, were outside his idiom and outside his magic.

He would have to see the witch.

The witch must have known he was coming, as she always seemed to know. She awaited him in the doorway of her pleasant cottage by the wildflower meadow, more wildflowers—daisies and buttercups—waving among the long grasses of the turfed roof. A nanny goat grazed beside the chimney, her long coat as white as the milk that stretched her udder pink and shiny. He saw no kid.

The witch was as dark as the goat was white, her black, black hair shot with silver and braided back in a wrist-thick queue. Her skirts were kilted up over her green kirtle, and she handed Weyland a pottery cup before he ever entered her door. It smelled of hops and honey and spices, and steam curled from the top; spiced heated ale.

"I have to see to the milking," she said. "Would you fetch my stool while I coax Heidrún off the roof?"

"She's shrunk," Weyland said, but he balanced his cup in one hand and limped inside the door to haul the stool out, for the witch's convenience.

The witch clucked. "Haven't we all?"

By the time Weyland emerged, the goat was down in the dooryard, munching a reward of bruised apples, and the witch had found her bucket and was waiting for the stool. Weyland set the cup on the ledge of the open window and seated the witch with a little bit of ceremony, helping her with her skirts. She smiled and patted his arm, and bent to the milking while he went to retrieve his ale.

Once upon a time, what rang on the bottom of the empty pail would have been mead, sweet honeyed liquor fit for gods. But times had changed, were always changing, and the streams that stung from between the witch's strong fingers were rich and creamy white.

"So what have you come for, Weyland Smith?" she asked, when the pail was a quarter full and the milk hissed in the pail rather than sang.

"I'm wanting a spell as'll mend a broken heart," he said.

Her braid slid over her shoulder, hanging down. She flipped it back without lifting her head. "I hadn't thought you had it in you to fall in love again," she said, her voice lilting with the tease.

"'Tisn't my heart as is broken."

That did raise her chin, and her fingers stilled on Heidrún's udder. Her gaze met his; her eyebrows lifted across the fine-lined arch of her forehead. "Tricky," she said. "A heart's a wheel," she said. "Bent is bent. It can't be mended. And even worse—" She smiled, and tossed the fugitive braid back again. "—if it's not your heart you're after fixing."

"Din't I know it?" he said, and sipped the ale, his wife's ring—worn now—clicking on the cup as his fingers tightened.

Heidrún had finished her apples. She tossed her head, long ivory horns brushing the pale silken floss of her back, and the witch laughed and remembered to milk again. "What will you give me if I help?"

The milk didn't ring in the pail any more, but the gold rang fine on the dooryard stones.

The witch barely glanced at it. "I don't want your gold, blacksmith."

"I din't want for hers, neither," Weyland said. "'Tis the half of what she gave." He didn't stoop to retrieve the coin, though the witch snaked a soft-shoed foot from under her kirtle and skipped it back to him, bouncing it over the cobbles.

"What can I pay?" he asked, when the witch met his protests with a shrug.

"I didn't say I could help you." The latest pull dripped milk into the pail rather than spurting. The witch tugged the bucket clear and patted Heidrún on the flank, leaning forward with her elbows on her knees and the pail between her ankles while the nanny clattered over cobbles to bound back up onto the roof. In a moment, the goat was beside the chimney again, munching buttercups as if she hadn't just had a meal of apples. A large, fluffy black-and-white cat emerged from the house and began twining the legs of the stool, miaowing.

"Question 'tisn't what tha can or can't do," he said sourly. "'Tis what tha will or won't."

The witch lifted the pail and splashed milk on the stones for the cat to lap. And then she stood, bearing the pail in her hands, and shrugged. "You could pay me a Name. I collect those."

"If'n I had one."

"There's your own," she countered, and balanced the pail on her hip as she sauntered toward the house. He followed. "But people are always more disinclined to part with what belongs to them than what doesn't, don't you find?"

He grunted. She held the door for him, with her heel, and kicked it shut when he had passed. The cottage was dim and cool inside, with only a few embers banked on the hearth. He sat when she gestured him onto the bench, and not before. "No Names," he said.

"Will you barter your body, then?"

She said it over her shoulder, like a commonplace. He twisted a boot on the rushes covering a rammed-earth floor and laughed. "And what'd a bonny lass like thaself want with a gammy-legged, fusty, coal-black smith?"

"To say I've had one?" She plunged her hands into the washbasin and scrubbed them to the elbow, then turned and leaned against the stand. When she caught sight of his expression, she laughed as well. "You're sure it's not your heart that's broken, Smith?"

"Not this sennight." He scowled around the rim of his cup, and was still scowling as she set bread and cheese before him. Others might find her intimidating, but Weyland Smith wore the promise-ring of Olrun the Valkyrie. No witch could mortify him. Not even one who kept Heidrún—who had dined on the leaves of the World Ash—as a milch-goat.

The witch broke his gaze on the excuse of tucking an escaped strand of his long grey ponytail behind his ear, and relented. "Make me a cauldron," she said. "An iron cauldron. And I'll tell you the secret, Weyland Smith."

"Done," he said, and drew his dagger to slice the bread.

She sat down across the trestle. "Don't you want your answer?"

He stopped with his blade in the loaf, looking up. "I've not paid."

"You'll take my answer," she said. She took his cup, and dipped more ale from the pot warming over those few banked coals. "I know your contract is good."

He shook his head at the smile that curved her lips, and snorted. "Someone'll find out tha geas one day, enchantress. And may tha never rest easy again. So tell me then. How might I mend a lass's broken heart?"

"You can't," the witch said, easily. "You can replace it with another, or you can forge it anew. But it cannot be mended. Not like that."

"Gerrawa with tha," Weyland said. "I tried reforging it. 'Tis glass."

"And glass will cut you," the witch said, and snapped her fingers. "Like that."

He made the cauldron while he was thinking, since it needed the blast furnace and a casting pour but not finesse. If glass will cut and shatter, perhaps a heart should be made of tougher stuff, he decided as he broke the mold.

Secondly, he began by heating the bar stock. While it rested in the coals, between pumping at the bellows, he slid the shards into a leathern bag, slicing his palms—though not deep enough to bleed through heavy callus. He wiggled Olrun's ring off his right hand and strung it on its chain, then broke the heart to powder with his smallest hammer. It didn't take much work. The heart was fragile enough that Weyland wondered if there wasn't something wrong with the glass.

When it had done, he shook the powder from the pouch and ground it finer in the pestle he used to macerate carbon, until it was reduced to a pale-pink silica dust. He thought he'd better use all of it, to be sure, so he mixed it in with the carbon and hammered it into the heated bar stock for seven nights and seven days, folding and folding again as he would for a sword-blade, or an axe, something that needed to take a resilient temper to back a striking edge.

It wasn't a blade he made of his iron, though, now that he'd forged it into steel. What he did was pound the bar into a rod, never allowing it to cool, never pausing hammer—and then he drew the rod through a die to square and smooth it, and twisted the thick wire that resulted into a gorgeous fist-big filigree.

The steel had a reddish color, not like rust but as if the traces of gold that had imparted brilliance to the ruby glass heart had somehow transferred that tint into the steel. It was a beautiful thing, a cage for a bird no bigger than Weyland's thumb, with cunning hinges so one could open it like a box, and such was his magic that despite all the glass and iron that had gone into making it, it spanned no more and weighed no more than would have a heart of meat.

He heated it cherry-red again, and when it glowed he quenched it in the well to give it resilience and set its form.

He wore his ring on his wedding finger when he put it on the next morning, and he let the forge lie cold—or as cold as it could lie, with seven days' heat baked into metal and stone. It was the eighth day of the forging, and a fortnight since he'd taken the girl's coin.

She didn't disappoint. She was along before midday.

She came right out into the sunlight this time, rather than lingering under the hazel trees, and though she still wore black it was topped by a different hat, this one with feathers. "Old man," she said, "have you done as I asked?"

Reverently, he reached under the block that held his smaller anvil, and brought up a doeskin swaddle. The suede draped over his hands, clinging and soft as a maiden's breast, and he held his breath as he laid the package on the anvil and limped back, his left leg dragging a little. He picked up his hammer and pretended to look to the forge, unwilling to be seen watching the lady.

She made a little cry as she came forward, neither glad nor sorrowful, but rather tight, as if she couldn't keep all her hope and anticipation pent in her breast any longer. She reached out with hands clad in cheveril and brushed open the doeskin—

Only to freeze when her touch revealed metal. "This heart doesn't beat," she said, as she let the wrappings fall.

Weyland turned to her, his hands twisted before his apron, wringing the haft of his hammer so his ring bit into his flesh. "It'll not shatter, lass, I swear."

"It doesn't beat," she repeated. She stepped away, her hands curled at her sides in their black kid gloves. "This heart is no use to me, blacksmith."

He borrowed the witch's magic goat, which like him—and the witch—had been more than half a God once and wasn't much more than a fairy story now, and he harnessed her to a sturdy little cart he made to haul the witch's cauldron. He delivered it in the sunny morning, when the dew was still damp on the grass, and he brought the heart to show.

"It's a very good heart," the witch said, turning it in her hands. "The latch in particular is cunning. Nothing would get in or out of a heart like that if you didn't show it the way." She bounced it on her palms. "Light for its size, too. A girl could be proud of a heart like this."

"She'll have none," Weyland said. "Says as it doesn't beat."

"Beat? Of course it doesn't beat," the witch scoffed. "There isn't any love in it. And you can't put that there for her."

"But I mun do," Weyland said, and took the thing back from her hands.

For thirdly, he broke Olrun's ring. The gold was soft and fine; it flattened with one blow of the hammer, and by the third or fourth strike, it spread across his leather-padded anvil like a puddle of blood, rose-red in the light of the forge. By the time the sun brushed the treetops in its descent, he'd pounded the ring into a sheet of gold so fine it floated on his breath.

He painted the heart with gesso, and when that was dried he made bole, a rabbit-skin glue mixed with clay that formed the surface for the gilt to cling to.

With a brush, he lifted the gold leaf, bit by bit, and sealed it painstakingly to the heart. And when he had finished and set the brushes and the burnishers aside—when his love was sealed up within like the steel under the gold—the iron cage began to beat.

"It was a blacksmith broke my heart," the black girl said. "You'd think a blacksmith could do a better job on mending it."

"It beats," he said, and set it rocking with a burn-scarred, callused fingertip. "'Tis bonny. And it shan't break."

"It's cold," she complained, her breath pushing her veil out a little over her lips. "Make it warm."

"I'd not wonder tha blacksmith left tha. The heart tha started with were colder," he said.

For fourthly, he opened up his breast and took his own heart out, and locked it in the cage. The latch was cunning, and he worked it with thumbs slippery with the red, red blood. Afterwards, he stitched his chest up with cat-gut and an iron needle and pulled a clean shirt on, and let the forge sit cold.

He expected a visitor, and she arrived on time. He laid the heart before her, red as red, red blood in its red-gilt iron cage, and she lifted it on the tips of her fingers and held it to her ear to listen to it beat.

And she smiled.

When she was gone, he couldn't face his forge, or the anvil with the vacant chain draped over the horn, or the chill in his fingertips. So he went to see the witch.

She was sweeping the dooryard when he came up on her, and she laid the broom aside at once when she saw his face. "So it's done," she said, and brought him inside the door.

The cup she brought him was warmer than his hands. He drank, and licked hot droplets from his moustache after.

"It weren't easy," he said.

She sat down opposite, elbows on the table, and nodded in sympathy. "It never is," she said. "How do you feel?"

"Frozen cold. Colder'n Hell. I should've gone with her."

"Or she should have stayed with you."

He hid his face in the cup. "She weren't coming back."

"No," the witch said. "She wasn't." She sliced bread, and buttered him a piece. It sat on the planks before him, and he didn't touch it. "It'll grow back, you know. Now that it's cut out cleanly. It'll heal in time."

He grunted, and finished the last of the ale. "And then?" he asked, as the cup clicked on the boards.

"And then you'll sooner or later most likely wish it hadn't," the witch said, and when he laughed and reached for the bread she got up to fetch him another ale.

Elizabeth Bear is the author of several novels.