Her father always called her "plain old goddam Amy." Then she told him it hurt her feelings, so he started calling her "Poga," his acronym for it, which he explained to other people as her nickname from their travels in San Pantalon, the little Central American country that he made up because he liked to see if he could get people to pretend that they had been there. Being called "Poga" still hurt her feelings but not in a way other people could catch him at.

She could hear his voice now just as if he had not been dead for four years. The eyes of his photograph, dusty and propped beside her coleus on the windowsill, seemed to evade her just like when he was alive.

He would sometimes gaze over her shoulder soulfully and tell her how important she was to him. Probably he hoped she'd share those moments with his fans.

The only time she could remember him looking into her eyes directly, really, had been whenever he got ranting about all the goddam kids who'd rather re-read goddam Tolkien for the goddam twentieth time than pick up something new and good and that was why we were so goddam poor all the goddam time. Then—only then—he seemed really to see Amy, just Amy, right there and as she was.

Gah. Thinking about him too much already. She grabbed a paper towel from the rack beside the plant table, spit on his picture, and wiped the dust off. "It's not like I'm trying to avoid you, asshole. I'm going back to The Cabin and all." She set it face down on the table.

She sighed, a pretty melodramatic sigh for plain old goddam Amy, and got back to packing, which wasn't much because her vacation clothes weren't much different from her working clothes; they were just her going-out in public clothes, elf-made and without blood, paint, and ink stains.

She didn't care much. In the working week, she put on her old-blood-and-fluids stained Wal-Mart tees and jeans to go in to the lab, photographed dead animals and bits of cadavers on her digital, and brought the pictures back here to do her drawings in her paint-and-ink-spattered sweats.

To go out with friends, she wore her elf-made stuff, which always fit, never wore out, washed clean, and was warm or cool as needed. Colin always teased her about owning

"Five golden rings!

Four tee shirts,

three sweatshirts,

two pairs of jeans,

and a warm pair of Mithril socks!"

because all they ever saw her in were those. Actually she wore other socks when her Mithril of Wyoming socks were in the wash, but Colin barely noticed her except when he wanted to be funny at her expense, or when it was cool to know her, which was any time Dad came up in conversation around people new to their clique. That was when Colin's arm gripped plain old goddam Amy's plump little shoulders, and felt way too goddam good, and the girl she saw reflected in his pupils was sort of cute, or had been cute once. Cuter anyway. A cuteness had been present and now was absent.

Gah. Making little jokes the way Colin and the crowd did. It seemed like she was inviting everyone—Dad, Colin—that she really didn't want to come along.

But now the tape was running in her head, how things always went when there was a new person in the crowd who kept glancing at Amy, trying to catch her eye, shyly wanting to know who this was. When that happened, and attention began to slip away from him, Colin would tuck her under his arm like a football and start explaining that she was The Amy, The Real Amy, That Amy, yes, Little Amy from Burton Goldsbane's Wonderful Books, and she had grown up in The Cabin, and the capitals would fly thick and fast, even orally.

Anyway she was just going up to The Cabin, as Dad had always pronounced it, capitals and all. (At least Dad had only orally capitalized The Cabin and Little Amy; when he wasn't ignoring her, Colin was a storm of capitals. Or at least a steady soaking drizzle.)

Nobody in Feather Mountain was going to give a fart in a windstorm what she looked like because they hadn't since she'd been sixteen and concentrating on how close she could get to the dress-code line without getting sent home. People there didn't know what she wore all the time in Greeley, anyway.

So she packed what she wanted, just dumped all her elven stuff into her duffel bag (twenty-six years old and she'd never owned a proper suitcase, talk about a perpetual student). That was enough for the week but her thought of Colin and his dumb little song made her feel too much like Poga, so she dutifully looked through her one big drawer of as-yet-unstained human-made clothes, seeing if she could make herself find something to take along and work on getting used to.

Well, no. She couldn't. Too scratchy, too clingy, too warm, deceptively warm-looking but not really warm, not right for eight thousand feet in March. Done. She stuffed the whole scratchy, clingy, chilly pile back in the drawer on top of—

Her soul.

Her hands scrabbled at the coarse fabrics, yanking the sweaters, jeans, and tees back out, tossing them any old way onto the bed behind her, and there it was, lying in the drawer, where she had just glimpsed a corner of it.

Folded away in the corner, small and gray, unpressed, uncared for. They said when you found it you always knew it right then for what it was, and sure enough, she did.

Though it was so much smaller.

And so much dingier than she'd remembered.

In her memory it had been about two yards of fine, patterned raw silk, iridescent, coruscating, "numinous and luminous and voluminous," centered around "a big bold beautiful textured satin valentine heart set in a deep blue diamond," as she had written in her journal yesterday, making her notes for her search of The Cabin. "As long as he was tall, exactly."

As who was tall?

Maybe she had written his name, whoever he was, in her journal. Had she packed her journal? She picked it up from her desk, closed it, and dropped it into her duffel bag.

Was she all packed? No, she needed to put in her toiletry bag and—her soul, right, she had just found her soul. She looked down at her hand and there it was, again.

Not a big piece of beautifully woven raw silk with a textured valentine at the center.

A two-by-two square of gray unhemmed muslin. It was dusty. Really, she thought she had kept her soul cleaner than this.

Plus she didn't remember that her soul had been marked in dressmaker's chalk, that weird shade of blue that only came in a Baudie's Dressmaker's Stylus, which you could only get at Mrs. Puttanesca's shop, where Amy had learned to sew.

Dear Mrs. Puttanesca, so patient. Piles of bolts of fabric. Warm summer street air from Feather Mountain drifting through the shop. Just the thought took her back.

You could get a Baudie's at any Wal-Mart.

That thought took her sideways.

Why would she think you could get it at any Wal-Mart?

Of course you could only get a Baudie's Dress Makers' Chalk Stylus at Mrs. P's, because the company had been out of business for decades but Mrs. Puttanesca had bought four big boxes of them way, way, back before Amy was even born. And nothing worked as well as a Baudie's, anyone who had ever tried one knew that, you drew on the fabric as easy and fine as a good dip pen on a nice hard paper with just the right tooth—so why, in her mind's eye, was Amy seeing a big rack of them on sale at Wal-Mart?

Amy never went into Wal-Mart.

Except a lot of her scratchiest, clingiest stuff came from Wal-Mart.

Well, that was why she didn't go there, obviously.

Weird wandering thoughts and memories were supposed to be common just after you found your soul. She'd seen that on Oprah or Ricki Lake or one of those shows, they'd brought in a bunch of young women and their mothers with strange tales to tell about acting weird. Amy couldn't remember much of what they'd said but she could see that white sans-serif caption in the corner of the TV screen: "My Daughter Found Her Soul and Now She's Weird."

She didn't need TV to know about it. Every woman in her crowd who had found her soul had gone all weird. Aimee had thrown over a dream job, just walked into her boss's office and said, "I quit" and walked out, and now she was down in Oaxaca painting big-eyed kids. Ami had come by one Friday to The Lowered Bar, where the usual TGIF crowd met, waving her red-and-blue flannel soul over her head, but before they even got a good look at it, she'd said, "My ride is here," and a pegason, ridden by one hell of a hot-looking elf, had lighted on the sidewalk in front of The Lowered Bar in a clatter of hooves and a thunder of feathered wings.

Ami had run out, the TGIF crowd following like puzzled kittens after a ball, and, as the pegason swung a wing forward and up to give her room, bounded into the saddle behind the elf, tying her soul around her waist. With three big flaps and a galumph, galumph, galumph, the pegason had taken off, not giving the Greeley cops any time to get there with an illegal-landing citation, and spiraled up a thermal off The Lowered Bar's parking lot.

Ami had shouted a promise to write (Amy thought, it was hard to hear over some wisecrack Colin was making), then the pegason had merged into a bigger thermal shot upward. With an elven sense of drama, Ami and her elf had silhouetted against the full moon.

"So perfectly elvish," Amy had said, and Colin had asked her about why she said that, over and over, and why she stared so hard at the elf, until she had changed the subject and started telling stories about all the different ways she'd gotten suspended from Feather Mountain high school.

In the next few weeks, Ami had sent just a few emails from Cody and Billings, and about a year later a jpeg of a much fatter, dumpier Ami proudly holding a pointy-eared golden-eyed baby in front of something that looked for all the world like the Magic Kingdom, and then nothing, not even a thank-you for the baby quilt Amy had made. (She had lied that the rest of the crowd had chipped in materials, though in fact none of them even mentioned Ami after some nasty jokes about the picture of the baby—really nasty jokes, Amy thought, everyone knows you can't take a picture of a half-elven and have it come out, it's the camera that does that, mirrors do it too, it was unfair to Ami and unfair to her child and simply unfair. But she hadn't said anything to Colin and the others. It had been a few months after she'd given up saying anything to them, and had just accepted her usual place in Colin's armpit and her occasional place on his lapel).

And as for Émye—so horrible. And it had happened right after she had found her soul, she'd just shown it to Amy when they had dinner together on Saturday, gone missing the next week, and then the first parts of her had been found the following Monday.

It had taken Amy weeks to persuade Detective Sergeant Derrick de Zoos, he of the sincere puppy-dog look, that she really had no idea what might have become of Émye beyond the ghastly details in the papers. Worse yet, he had needed to keep coming back to break more news to her, as they found Émye's head, then the shallow grave with most of her, and then the rest, and then the place where she had been held and tortured, and so on, place after place, name after name to check with Amy's memory, until finally it had all led to nothing. Amy's memory of things Émye had said or people Émye had introduced her to contained no name they could connect to that old Q-hut above Eagle. None of the stores where the knives had been purchased, or the places Émye's torn body had been disposed of, had rung any bell for Amy, and Amy seemed to have been her only public friend (not counting the rest of the crowd, which had not known her at all except as a girl who sat next to Amy at TGIFs at The Lowered Bar).

In retrospect Émye had been the real star of the crowd as far as Amy could see, far more interesting than the daughter (and favorite character) of Burton Goldsbane, let alone an illustrator for biology and medical textbooks.

Yet Émye, half-elven, supernaturally beautiful, had merely hung around shyly, gracing the clique without the clique ever realizing it had been graced; Amy was the only one who regularly called Émye and made time and room for her. Perhaps that was why, when they found Émye's cell phone in the grave, only Amy's number had been in its memory.

She could only assume that Émye must have had some entirely separate, secret life over the border, that finding her soul (Émye had a bedsheet-sized piece of pure white linen) had made her misbehave somehow in that other world, and something or someone had punished her. Or maybe Émye had been chosen for some dark sacrifice because of something about her soul. Or perhaps that it was all a coincidence and it just happened that shortly after finding her soul, Émye was in the wrong place at the wrong time. But Amy had no way to know which it had been, and just because she had been Émye's only friend in no way implied that they had been close friends.

Eventually she persuaded Detective Sergeant Derrick de Zoos that she knew no more than that, and he stopped calling her—about that.

Unfortunately, by then, Derrick had acquired another interest in Amy entirely.

Derrick really was a very nice guy, and the cards, the flowers, and the invitations were flattering. She just had to constantly remind herself that she was not the sort of woman who dated cops, at least not the kind who got serious about them (and if you were going to date Derrick de Zoos, you'd have to get serious about him—he was that type). She could not imagine herself sending him out every day and wondering if he would be shot at, or having mischievous precocious cop-kids who worshipped their father, or retiring to some beachfront community somewhere where they could spend most of their time barbecuing and going to movies.

She wanted Derrick to give up courting her. But it had to be of his own accord, because she couldn't have borne bluntly telling him to go away (oh, those big brown eyes would have been sad!) Besides, her few times going out with Derrick had been fun, or at least a welcome break from hanging out with her old college friends at The Lowered Bar.

Plus going out with Derrick upset Colin, who fancied himself a dangerously masculine man of the world, but who was actually, (though still handsome-faced in the way that had conquered a dozen nerdy freshman virgins) a soft doughy guy who lived on junk food, wrote software, and watched a lot of movies. Derrick's being a real live masculine cop made Colin get pissy in a way that reminded her of the way Dad had gotten whenever anyone mentioned Tolkien.

A cop's girlfriend, lover, or wife should have a sturdy brown burlap soul, or perhaps a pure white linen one, and hers—well, it wasn't the iridescent raw silk she had thought, now was it? She looked down, again, at the square of unbleached muslin hanging limply from her hand. Little gray dust bunnies drifted down from it onto the floor and the toes of her Bean Snow Sneakers.

She lifted her soul to eye level, grasping a corner with each hand, and shook it out gently, tumbling the remaining dust onto her feet and into her cuffs. That outline in blue chalk was obviously-–

Amy's father had a shrub of gray hair on top of his head, desert-sky eyes, and a basketball-belly on his otherwise scrawny frame. You noticed him, visually. But when Amy thought of him, most of all she remembered his clatter: the bang of the manual typewriter as she played around his feet, which had given way to the squirr-whuck-chik! of the electric welcoming her home, along with the Oreos and milk and the silly poems on the kitchen table.

Later, there had been the house-shaking daisy-wheel printer covering the sound of her running downstairs to get into a car with primer on the fender, a sullen boy in the front seat, a case of beer in the trunk, and disappointment in the offing because the boy was never quite how she thought boys should be.

Finally, during her college breaks, after he had the money for a quiet laser printer, she had awakened early every morning in Feather Mountain to the thunder of his clumsy stiff fingers pounding against the uncooperating keys, all precision aged out of his aching hands as they walloped a final three books into the word processor, as if he were regressing back onto the manual typewriter.

The window-shape of late-winter sunlight jumped sideways on the living room floor.

Amy had been in a reverie. Her soul still dangled from her upraised hands. Her arms were sore. Had she really stood here staring into that cloth for half an hour?

She switched on the bright lights over her drawing table and spread the soft cloth on it.

The outline of a heart—not a valentine heart, either. Most people would see only a blob, but Amy recognized a real human heart, lying on its atria, drawn from directly above. The chalk line showed no skips, no sketch marks, no hesitations—her soul must have been pinned tight to the table, not to have wrinkled at all as this was drawn. The unbroken chalk line had the assurance of a hard edge in an overdeveloped photograph. Yet it was just the right width and color to be Baudie's . . .

The drawing on the other side was of a human heart, at the same scale, lying on its right ventricle.

She spread her soul out on the light table. Sure enough. The blue lines on one side matched those on the other, as if the Baudie's Dressmaker's Chalk Stylus—had somehow gone right through the fabric.

Could she make her friends understand how strange this was? Now and then, for some complex patterns, if you're sewing or cutting out, it can be handy to have a mark on both sides, she would say. They would all look bored. To the guys, sewing was girl stuff. To the girls, it was something authentic for authentic Third World peasant women to do in their authentic culture so that authentic woman entrepreneurs could bring it up here and sell it in little stores that just dripped of authenticity.

Or maybe the real reason they would all look bored was just that a brilliantly drawn chalk line for sewing was the sort of thing that plain old goddam Amy would talk about. But they'd let her talk, so long as she didn't go on too long about it. See, she would say, already afraid she was boring them, it's pretty rare that you mark both sides and, if you do it at all, normally you only make a few marks on one side where it's going to be hard to see what you're doing after you've pinned something.

For a cut-out line like this, you'd never mark the whole way round. And most certainly of certainlies—that had been a favorite phrase of Dad's in his books about Little Amy at the The Cabin, so it might suppress their impatience while she finished explaining that nobody could possibly trace all the way around in a medium like chalk on muslin, with no bunching or shaking or anything. I've been doing med illo for years and I couldn't do that. Leo-fucking-nardo couldn't do that on a good day.

They would all nod solemnly, Colin would say something sarcastic, and the clique would go back to quoting television at each other.

Maybe finding your soul made you cynical too.

The rectangles of light from the sunny window distorted further into rhombi, and jumped across the floor again.

Another reverie. Forty-five minutes this time, though she'd had fewer thoughts, at least fewer she could recall.

She wadded up her too-small, colorless, strangely-marked soul and tossed it into the duffel bag with her too-large, colorless, perfectly-self-maintained elven sweaters.

On top of her soul she put her meager toiletry bag: toothpaste, shampoo, aspirin, and hairbrush. No makeup. What would be the point? There wasn't going to be anyone at The Cabin except her, and she could never get things to come out anyway no matter how long she stood at the mirror.

Or had she invited someone to The Cabin?

She closed up the duffel, shouldered it, and went down to the convertible that she'd inherited, along with too much else, from Dad.

When she turned a different way, the old LeSabre seemed to perk up and sing, as if it didn't have to do something it hated, this one time; whether it was getting away from The Lowered Bar, or from Greeley, or it was all just her imagination, the car sounded happy.

Going east to west across the Front Range, you point the car's nose down the straight-as-a-bullet two-lane road, stand on the accelerator, and go into that mental groove where you can run down a country road flat-out and wide-eyed, alert and quick enough not to rear-end a frontloader, T-bone a hay truck, or put an antelope through your windshield. You chew up road as the mountains loom, and make sure you stay alert.

The phone rang. She pulled the headset from her neck up onto her ears and said "Hello?"

"Hey, there, this is Sergeant Derrick de Zoos of the Colorado Bureau of Cute Chick Control—"

"Oh, my dear sweet god, how long did you spend making that one up?"

"Hours and hours," his voice said, a warm smiling baritone in her ears. His voice, she thought, was even better than the eyes and the muscles. Now if he could just stop being a cop and lose that sense of humor.

She reminded herself to focus on the road. "Well, maybe it just needed a few more drafts."

"Everyone's a critic. I bet your dad always said that."

"Almost as often as he said 'Goddam Tolkien.'"

"What did he have against Tolkien?"

"Several million book sales and a vast repeat business. So what are you actually after, here, Detective? Am I charged with anything cool?"

"You're charged with being cool, how's that? Here I am, a detective, all set for major crimes, and no major criminals have turned up, so of course I thought of you."

She saw brake lights far ahead and took her foot off the gas, letting the LeSabre slow down. "Aren't you worried about someone taping your calls to me?"

"They're nothing compared to the calls I make to other girls."

Amy couldn't help smiling; she liked Derrick whether she wanted to or not. "So let me guess. You're soaking up taxpayer time and money on the phone to me because you're finally getting a weekend off?"

"A three-day weekend," he said, in a tone approaching religious awe. "So, first question, does it take three days to wash your hair?"

"Day and a half, tops."

The brake lights had been a big old F250 turning off into a dirt road; she put her foot down again and the LeSabre pressed pleasantly against her back.

"Old boyfriends coming to town? Dental appointments?"

"They're rotating a paratroop regiment home from Avalon, and I should see a brain surgeon, but no." She liked bantering with the detective; Derrick got banter in a way that none of her crowd did, understanding it was a mutual game and not a public performance.

Belatedly, she realized she had just put herself into a corner, when Derrick asked, "So what lame excuse are you going to give me for not seeing me?"

"Oh, god, I should have seen that coming. There's two reasons it will be tough, but tough is not impossible. One, I'm driving up to The Cabin—right now, actually on the road—to spend a week."

"Your dad's old place?"

"You remember everything I say."

"I heard the capitals, so I recognized the place right away. But I thought that your dad's foundation was putting artists-in-residence into it."

"Right now it's in-between. Samantha just left, and Piet isn't due for another six weeks, and I get to use it during in-betweens. So you might have to be willing to drive up to Feather Mountain on one of your days off."

"Deal!"

Doh! Why had she done that? Was she trying to keep Derrick pursuing her? And if so, why? And wouldn't it be awkward with three of them there?

That was, two.

The road lurched a little sideways and her breath caught before she brought the car back into her lane. Thank all the gods for dry pavement and good tires. She must have been off in like a two-second reverie.

"Amy? Are you still there?"

"Still here," she said, thinking good question, Detective.

"Did I get too pushy?"

"Not at all," she said. "Just had to think and drive and didn't have any brain cells to spare for talking. But yes, come on up to The Cabin this weekend. I want you to. The question is whether you want to, because the other thing is, just this afternoon, I found my soul, so if you come to see me, I might be pretty weird, you know."

"And you're driving?"

You weren't supposed to do that, Amy remembered, belatedly. "Derrick, I feel fine."

"It's not a law or anything," he said, "but you are going to be kind of out of it and accident prone, so be a little careful, okay? And you're making me wonder about that long pause on the phone."

She was about to make something up, tell him there was a tractor on the shoulder and cars coming the other way, but the words stuck in her throat, like they always did.

"Or is that sounding too protective?" he asked.

"Maybe a little."

"Well, it's pure self-interest. I want you around to reject me for years to come. How do you feel right now?"

"Weird but not bad and not out of it. I did have a couple of reveries right after I found it. But as far as I can tell, I'm alert now."

"Well, I know this is hovering and I know you hate it, but call me when you get to The Cabin, okay? Just so I know you got there. And then we can figure out whether you really invited me or I just trapped you into it."

"Derrick, sometimes you are too smart for both of our good."

"Whatever. Anyway, call me from The Cabin? Then maybe we'll make plans or not, but I'll know. Call the cell—I don't get off till three a.m., but I don't expect I'll be doing much of anything, unless Greeley gets a lot tougher than it's ever been up till now. Can't even really hope for a good stabbing."

"The tough act isn't working, either," she said, smiling into the phone and hoping he heard it as teasing. "All right, I'll call you."

"You will?"

"Actually, yes. I promise. I just realized I probably did worry you some, and besides, I kind of want to have someone looking for me if I don't make it there. But as far as I can tell, I'm fine now, really."

"Okay. 'Preciate it, Amy."

"No problem, Derrick. Have a quiet night."

She crossed 25 into a series of dips and rises, where in dinosaur times the Pacific Plate finished skidding under North America like a piece of cardboard under a tablecloth. Wrinkles and folds in the Earth rise and steepen and cram together to become the Rocky Mountain Front, an area of astonishing beauty populated by elves and fairies illegally squatting below the Wyoming line, Buddhists and anarchists and old tommyknockers who can tolerate the elves, and, south toward Raton, bordersnakes, demons, and Apache ghosts.

Other ghosts are everywhere, silent, unspeaking, forever watching the invaders. Dad had taken her out to watch them gather and dance beside the borrow pit in the moonlight, countless times.

Not the borrow pit!

The lovely dark pool at the foot of the pine-covered slope from The Cabin with a twenty-foot waterfall falling into its north end. The pool that tumbled down the steep bouldery slope to Maggie's Creek in its southeast corner. She remembered vividly. The ghosts, Utes mostly, had come to dance on the flat rock, as broad as a tennis court, by the waterfall, in the moonlight, and she and her father had sat watching them till the sunrise swept them away.

Cops had found Dad floating on his back in the open water around the waterfall, nude, dead of exposure, one bright sunny February day. Pike and ravens had been feeding on him for a few days, and his blue eyes, typing-strong fingers, and sardonic lips were already gone; they had had to identify him by his teeth.

The sheriff's office had been mystified by the $400 cash on the front table but Amy hadn't. She'd had to tell them that that was $300 standard, $50 premium for getting the exact physical type (young, pale, black haired, size four or smaller, ski-jump nose, fox-faced), plus $50 for driving up from Boulder or Fort Collins. They found a bunch of escort-service phone numbers on his computer and that ended the mystery; they'd even located the girl who had driven all that way to a door that didn't open and lost a night's earnings by it. The time of his call to the service established the last time he'd definitely been alive, six days before he was found.

Amy had always wished she could find a way to apologize to the girl for that. But then she had always wished she could apologize to all the vampire-brunette pixies. Dad liked to say that he drank cheap and hated Tolkien for free, so girls who were born to play the lead in Peter Pan were his one expensive vice. He had been saying that ever since Amy was old enough to understand why she was supposed to find somewhere else to be, or stay very quietly in her room, about once a month.

Later on, in her personal finance course, she had sat down and figured out that he had dropped a bit over five k a year on his "one vice." Run that through compound interest by twenty years, think about what they could have had during those years, and the figure had made her eyes water. In her journal she had written I am changing my major from business to art and biology so I won't have to look at things that are quite so upsetting.

How far had she come over the rising wrinkles in the continent? It seemed like only five minutes in the groove, with the seat pushing against her back and the motor tached up past 4, but no, it had been almost an hour by the clock. The sun was most of the way down now, the towns farther apart, the mountains close, their shadows already stretching far out behind her so that it was night here and day in the sky. She was almost to Van Buren, at the foot of Maggie's Creek Canyon.

She topped the last rise before Van Buren, and the truck stop's neon island in a sodium-glare pond welcomed her into the dark below. She put her blinker on—she had skipped lunch, her bladder was about to burst, and the needle was near E. She glanced up and had to brake hard to make the last parking lot ramp into the truck stop. Her car fishtailed on the gravel but the passenger side door didn't quite kiss the BP stanchion (after a nervous split-second). Then her front tires grabbed pavement and she crunched over the gravel and up to the pump.

No hurt, no foul, as Dad said whenever he fucked up without totally fucking up, which was pretty much the average for Dad.

She gassed up, paid, peed, and then decided to move the car over to the main parking slots and sit down to eat at the counter. Derrick was right. If she was going to be driving within a few hours of finding her soul, she really ought to take some care of herself, for the sake of other drivers if nothing else. Might as well make sure she was comfortable, well-rested, and prepared, since the trip up Maggie's Creek Canyon Road in the dark was going to be stressy.

How had she let it get so late? Then she remembered that she had spent about an hour and a half in reverie. Aimee and Ami and Émye had all said that you forgot things a lot when you first got your soul back, though it seemed to Amy that she had been remembering things rather than forgetting them. Except that whatever she had been remembering, she'd been forgetting again.

Really, it was confusing and disorienting. She must've been driving a bit spaced out, but probably awake enough and therefore safe enough. She hoped.

Her usual double-burger-with-nothing had cooled to about room temperature, and the long hand on the clock had jumped halfway round. She wolfed the burger before it could get colder, gulped her slightly warmer chili, and left her lukewarm coffee on the counter, begging a refill with fresh hot stuff for her thermos. Forty minutes for a burger at a counter; life was slipping away just like that.

The last time she had come through here had been with her friends, with Colin sitting in the passenger seat of the red Miata she'd had then, grabbing the doorframe as she went up Maggie's Creek Canyon at a perfectly reasonable pace. It had been for Dad's funeral. Behind her there had been two more carloads of her friends, supposedly all there to support her through Dad's funeral, and actually along to be able to say that yes, they had known Little Amy in college, and been to The Cabin, and even been at Burton Goldsbane's funeral. It was the ultimate privilege—or payment—for having consented to be friends with plain old goddam Amy.

Extra privileges, such as actually riding shotgun in Poga's Miata, knowing the real story behind that Poga nickname, and being able to tell people that Little Amy drove like a lunatic, came for agreeing to sleep with her or at least to crash on her couch.

At the funeral she had almost heard her father whispering in her ear what he said often when he was drunk; Amy, Poga, Amy-Amy-Poga, I deal in lies all the time, little Poga, and the first thing to keep in mind is that to lie well you can't lose what the truth is. Disappear into the jaws of your own lie and it will digest you and leave you as a little pile of mendacious poop by the road. So lie all you want, Poga, but don't let the goddam lie eat you.

She had kind of enjoyed the shocked look on her friends' faces when they saw Feather Mountain and The Cabin and the waterfall pond the way they were. . . .

Which had been what?

No time to think about that now. She was into the canyon. In daylight this place was gorgeous, at night a scary challenge, though a familiar one. She didn't need to see anything more than what was in her headlights—she felt, or just knew, where things were and where she was. The rock walls, brief pullouts, and steep drop-offs were where they belonged, held in place by her memory, and marked by the sudden flashes of the bright mad dance of stars between the peaks, spires, and canyon lips.

She knew and watched for the game trails across the road. In icy late winter, in the last hour of light and the first hour of darkness, there were often deer and coyote, even elk or bear, heading down for a drink from fast-flowing Maggie's Creek, which never froze all the way over. Or you could see a Ute ghost, or even an elf flying low to follow the road, and be startled just as you came onto black ice, and be into the canyon before you knew it—though as long as some of the drops were, you'd know it for much too long.

A mountain road at night is busy, if you intend to make time and still get there alive. Amy had learned to drive on this road but it still required her full attention. She could never remember every place where shadow lay on the road all day long so that runoff dribbling across the road turned into black ice, suddenly under the tires, quick, thin, slick, invisible, and hard as death itself. Traffic coming the other way compelled her to constantly pop brights on and off, and she was always braking behind locals who saw no reason to hurry, or pulling into turnoffs to let other locals pass, blinking from the bright headlights in the rearview mirror, peering ahead for the not-pulled-over enough car with naked, semi-drunk kids in it that could be in any pull-off.

She wondered idly how many of these turnoffs she'd gotten laid in, during high school. Maybe the Burton Goldsbane Foundation would like to put up some small monuments: "Little Amy Was Slept With Here." And by her bedroom window, a statue of Burton Goldsbane himself, rampant with a puzzled expression—

Why by her window?

Approaching the blind curve that often had elk on the road just beyond it, she felt the reverie reaching up for her as if it were big, strong hands with unnaturally long fingers trying to cover her eyes, touch her body, stroke her—Never mind! She was driving the goddam canyon and the reverie would just have to leave her alone. The reverie vanished like the blur does when you focus a telescope.

With the very small part of her mind that had time to think, she was glad, almost smug. No reverie was going to shove her around. When she emerged at the head of the canyon, driving across the long truss bridge that leaped the raggy head of the canyon, and up into Feather Mountain Park, she glanced at the clock. As always, it had taken only about half an hour but she felt as if she had been driving all night.

Feather Mountain Park is not terribly impressive, as parks go. When she had gone off to college and met people from other parts of the country for the first time, Amy had forever been explaining that she had not grown up in a national park, that a park is a wide flat space between the mountains with too much wind and not enough rain for trees or crops, but perfect for horses and cattle. "Aryan Masculine Paradise," she used to explain. "Room for many cattle for the Tamer of Horses, and also lots of room for playing with guns and driving drunk real fast. Lots of long views you can snipe at federal agents from. Roadhouses with six country songs, none changed since 1970, on a thousand year old jukebox. When the Lord of the Park wants babies, there are local girls, dumb as rocks, blonde and well-knockered, drinking under-age at every roadhouse, drunk as shit and desperate to move out of their parents' house. And lots of room for a man to build his cabin—or park his doublewide. With all that going for it, what's a few months of below-zero, a wind that never stops whistling, and a little isolation and insanity?"

For some reason that had made people uncomfortable, though redneck jokes were common currency at UNC, especially among people who were afraid that they might not have scraped all the redneck off yet. After a while she made the connection and stopped telling those jokes; the problem wasn't what life in Feather Mountain Park was like, or that people felt bad about laughing at it. The problem was that the kids who had devoured all of Burton Goldsbane's Little Amy books did not want to picture sweet, dreamy Little Amy out on the backroads with older boys. Colin found it a little too interesting. Maybe that was why she stuck with him, though she never talked about life in Aryan Masculine Paradise any more around him.

What everyone had wanted, Amy thought, was to claim friendship with Little Amy from the books, with shy bookish good looks and a dreamy artsy iridescent valentine-centered soul; it didn't matter whether they wanted to worship her or win her heart or debauch her, they wanted Little Amy, and while she might have been perfectly happy to be worshipped or loved or debauched—better yet, all three—she just didn't have that iridescent soul.

And that brought her back to the thought of what was in her duffel bag. She had had such a clear picture in her head of her magnificent soul, and here she had a gray rag with a brilliantly drawn technical illustration: a real heart and not a valentine. Why had she ever gone looking for it in the first place, if it was going to turn out like this?

She topped the rise and looked down on the town of Feather Mountain. She'd also tried to make a joke out of the observation that there was a name shortage out here, that towns very often were named after prominent local features and so was everything else within reach, Feather Mountain standing above Feather Mountain Park where the town of Feather Mountain lay at the crossing of Feather Mountain Road and Maggie's Creek Canyon Road; she said when she was little she didn't know that anywhere could be named anything except Feather Mountain and Maggie's Creek. But nobody else thought that was weird, so she gave up on that joke too.

In the night with the miles of blinding-silver snow all around it, Feather Mountain was at least interesting, visually, and maybe even attractive. The sky was spattered with stars; you could see so many up here, down to very dim ones, and the moon had not yet risen.

She crossed the last stretch of Feather Mountain Park on the swooping miles-wide arcs of blacktop as the town popped in and out of view, until finally she came over the last low ridge just above the town and the wild spill of stars vanished in the glare on her windshield.

Two blocks of façade-style buildings with steep pitched roofs behind the façade, the real old-timey places from when this had been a tank town on the narrow gauge. Maybe twenty frame houses, Sears railroad bungalows that the real estate people now called Victorians, clustered around those two blocks, and then around that was the usual sprawl of aluminum sided fake frame houses, prefabs, and mobile homes on gravel streets. Out on the edge of that disorderly cluster, linked to the downtown by the other well-lighted street, lay a huge sodium-glaring parking lot surrounded by Wal-Mart, McDonald's, KFC, and Gibson's; the glare illuminated the irregular sprawl of mobile homes uphill from the parking lot.

Amy's LeSabre shot by the façade row of Main Street. No light on at Mrs. Puttanesca's—but what would you expect at nine o'clock on a Friday night?

She would have to make some time for a visit. She hadn't talked with Mrs. P since the funeral.

Just beyond the streetlights, as the stars popped back out of the black sky, Amy took the familiar turnoff up the steep winding road to The Cabin. Over the first hill, down into the little draw among the pines, and the friendly dark closed around her; she seemed to drive into that vivid spill of stars as she made the long climb up the main hill.

There were several houses back here, and she passed them all without seeing any sign of life. When she came to the driveway for The Cabin—actually just a place where the road narrowed and a sign announced that this was now private property rather than a public road—she was relieved to find that Bartie Brown had been up there with his snowplow, since when she'd known him in high school he'd only been reliable about getting beer. But when she'd talked to him to arrange the plowing, he'd rather shyly said that nowadays he had four trucks and was growing into a real business, and had asked permission to put up one of his advertising signs beside her private road.

She laughed when she saw his sign; the name of his company was How Now Brown Plow. Possibly there was more to Bartie than she'd realized ten years ago—maybe not being drunk and high all the time had something to do with it.

At The Cabin she parked in the same spot under the built-on carport where she had always parked her old VW Bug during high school, and her red Miata during college. "Plain old goddam Amy, home again," she said, aloud, but somehow it lacked the bitterness and irony she had intended. The car door opened into the expected blast of cold, and she pulled her duffel from the back seat and shouldered it up.

What was she doing here?

The question was what she had been trying to remember. Her whole reason for going up to Feather Mountain and The Cabin had been to look for her soul (a big expanse of vivid iridescence, in raw silk, with the most glorious embroidered ruby-red Valentine heart at its center), which she was sure was somewhere in one of the elf-crafted cedar chests along one wall of her bedroom.

But she had found her soul. It was right here in her duffel. What was she doing here?

She had reason enough to want to take some time off, but once she'd found her soul, she could have just turned left on 25, headed down to Denver or Santa Fe or even into Mexico, or picked up 70 in Denver and headed to Vegas or L.A.

She still could. If the weather didn't suit her clothes she could just buy clothes on the way; her job was to keep her busy and because she liked saving money of her own, but she could buy a new wardrobe any time she wanted one, she just never did. She could head to somewhere sunny and spend the next week in gauzy bits of fabric that cost more than her first car, in a hotel room that cost, for a week, what her apartment cost for three months, and live on umbrella drinks and desserts if she wanted. And she just might want.

No point in running the canyon again, though. Not in the dark when she was tired. Tomorrow could be another day.

Inside the front door, she found six tied-up garbage bags.

The Foundation had said that they had thoroughly checked Samantha out of the place, and yet they'd left these lying around? She had some bones to pick with the manager—

There was a pile of dishes in the sink, too. Had they not cleaned up at all, or—

She opened the refrigerator.

Fresh milk and fruit, bologna that couldn't have been more than a couple days out of the store.

There was some little sound from upstairs. She reached for her cell phone, thought for a second, and dialed.

"Derrick de Zoos."

"Derrick, it's me, Amy. I'm at The Cabin, but I want you to stay on the line with me for a little bit, if you have time and you can. I think there's someone else in here, squatting in The Cabin."

"What?! Get the hell out of there—"

"Easy. I think I know who I'm going to find. And it will be fine. I just want you on the line just in case. If something doesn't sound good, call the Larimer County Sheriff and tell them to send a deputy up here, they'll know the place, but I think it's all fine. I just want a back up plan in place in case this isn't who I think it is."

"I don't like you taking chances—"

"And I don't like you being protective, but we'll both have to live with it. My guess is it's Samantha, and trust me, she's harmless. And a friend. I just want you on the line in case a couple Texas-hunter assholes are squatting in here. But I bet it's just Samantha."

Samantha was a waif-thin, tiny, black-haired girl who churned out picture book scripts at a terrifying rate, showing great promise without ever quite selling one.

Amy carried her duffel up to her room as a way of temporizing. Since whoever was in the house didn't seem to have much furniture, and the only bed was in Amy's room, it seemed like the place to look.

"What are you doing now?"

"Climbing the stairs, Derrick. Going to the only room with a bed."

Amy's room, with the furniture her mother had given her before leaving, and Dad's office were the two rooms the Foundation required to be preserved pretty much as they had been, though Amy's room was a bit neater, and Dad's office phenomenally neater, than they had been when anyone lived there. Not to mention that they had taken down all of Amy's Kurt Cobain posters and dug the Care Bears back out of storage.

She'd kept the same bedroom set—bed, end tables, dressers, chests, and so forth, though. Her mother had returned to Elfland when Amy was too small to remember, but had left that bedroom furniture as a parting gift, and even after the money suddenly poured in following the unexpected success of Amy and Titania, that hand-carved elven furniture had been much the nicest stuff in The Cabin.

Dad had bought good things, all leather and oak and very Scandinavian, that were now in storage; he'd left Amy's room alone because it was hers, and his office because he could not bear the thought of changing anything and possibly jeopardizing the amazing luck that had taken him, after fifteen Little Amy books, from a reliable seller for every library's collection, and the recipient of a few fan letters every month, to the Times bestseller list.

Probably he had made 99% of the money he ever made in the last six years of his life. She wondered what he might have done differently if he had known that those were the last six. Probably written one less Little Amy book to make time for the series finisher he always said he would do some day, spent a little more time traveling, and had hookers up at The Cabin twice a week. And drunk more, laughed more, and eaten more pizza-with-everythings. Dad hadn't been the type to mourn about tomorrow, no matter how inevitably it was closing in. Which had something to do with those times in Amy's childhood when she had been forbidden to answer the phone because it might be "the money bastards," Dad's expression for bill collectors, "they're like goddam Tolkien's goddam orcs but not as well written, Amy, and if you talk to one on the phone he can steal your soul."

The stairs she ascended, and the balustrade were elf-carved, too, part of the list of things Dad had put into the cabin, like replacing the pinewood floors with maple and the plain old thermopane windows with old-fashioned double sashes, to make it more like The Cabin in the Little Amy books. When she'd been nine, there had been a steel utility stair he got for free from a warehouse that was being torn down, and they had rejoiced at getting to spend two weeks installing it, finally replacing the strapped on extension ladder they'd used before then.

"Talk to me, Amy, this is scary."

"You're scared? You've got a gun and you're eighty miles away."

At the top of the stairs, she flicked on a light and walked down to her bedroom door, far down at the end of the hall (at least the place had always been big).

When she flipped the light switch, she gasped.

"Amy! Are you okay!" Derrick's voice in her ear was demanding, as if she were a patrolman about to do something fatal.

Her soul—what she thought was her soul—what she had thought was her soul—was on the bed, as a quilt. A big, gorgeous, elven-made quilted comforter, with a raw silk face printed and embroidered with the pattern she remembered so well, a very nice one and it would probably have cost a thousand dollars at the gift shops in Cheyenne or Sidney, but nonetheless it was not a soul, it was just your basic shiny elf-quilt, astonishingly warm, eternally durable, fascinating and elegant.

But a quilt. Though the pattern was indeed just as long as he was tall, and—

"Amy, are you okay? Say something. I'm dialing Larimer Sheriff's right now—"

"I'm fine, I was just startled by something that has nothing to do with anything, sorry I worried you, you don't need to send the deputies."

Of course she remembered that quilt vividly, now. She had been tucked under it clear back when she was younger than Little Amy in the books. She had lain on it with her homework open in front of her while she chatted on the phone about keggers and shopping trips down to Boulder or Fort Collins. She'd debated taking it to college with her.

"I know you'll hate my asking, but are you okay?"

"I'm fine," she said, and realized how husky her voice sounded. Her face was wet. "Just one of those finding my soul things. I've got PMS—Perceiving My Soul—okay?"

"I think it's weird you can joke about it."

"Well, I can cry, too."

"Are you?"

"Mind your own business."

Amy just could not believe that she had remembered her fucking bedspread as her soul. She had lived so close to the Border for so long—Wyoming was less than half an hour's drive up the highway from here, one low range and you'd be descending into it—and somehow she had managed to make a mistake like–

"H'lo?" The quilt moved. "Hello?" The voice was sleep-drenched and sad. An arm, in a blue flannel sleeve with Han Solo on it, reached out from under the quilt; and a surprisingly alto voice croaked "ah shit, ah shit, ah shit," as if it had not been used in months. The quilt flipped back revealing a small, painfully thin woman, big eyes and liver-lips beneath a messy mop of jet-black hair that made her look like a dead dandelion. She groped for her thick horn-rimmed glasses, on the bedside table, like an old drunk feeling around for his bottle, pulled them on with a grimace, and blinked at Amy through a cloud of blear.

"Derrick," Amy said, "it's what I thought, and it's fine, 'kay? I need to talk to Sam now. Thanks for being there and putting up with me and everything."

"All right. Can I call later about maybe—"

"I'll call you. Promise. Gotta go." She clicked off and looked at Sam expectantly, not even considering being angry; this was too perfect and too typical.

"Ah shit, Amy, I guess I should try to explain this or something."

"Well," Amy said, "you're not in much shape to explain anything, but I bet I can. After the fellowship ran out, even though you wrote something like ten picture books while you were on it, you still hadn't sold anything, so you didn't have any money or anywhere to go. The next fellowship person wasn't due for more than two months, so you put your stuff in storage and since you still had a key here, you stay here, sleep in my bed, because it's the only one here, and write at Dad's desk or the kitchen counter, and keep hanging on and hoping your agent will call or something. You're living on mac and cheese and bologna sandwiches. That about cover it?"

"Yeah, I guess it does." Sam sat up. "You're not mad."

"No."

"Why not?"

"Dad's will set up the Foundation to support people who kept swinging at writing no matter what. I think I have pretty good proof the Board was right about you. And I'm probably only here for a day or two, and I know perfectly well you'll take better care of the place than I will. Do you have any money at all?"

"About three hundred in cash. I could give it to you if—"

"Not what I'm thinking about. I just wanted to make sure you're okay. Really. But get dressed anyway. I'm forcing you into slavery—I have a trunk load of groceries, because I had been planning to be here about ten days, and you get to help carry them in."

"But it's your house," Samantha said, climbing out of bed, unselfconsciously changing into the jeans and sweatshirt from the bedpost. "I'd be mad."

"Then I'll never hide in your house. Things have been a little weird lately, and I could use having some company, and you probably need some variety in your diet. Let's just get the stuff in and then we'll sort it all out over some frozen pizza and Castles and Fat Tire."

"Is it okay to say I love you forever?"

"Only if that means I can tease you about the Star Wars jammies."

Sam shrugged and shook her black bangs out of her eyes, finger-combing her thick mass of hair. "Warm. My size. Clearance at Wal-Mart. Helps me stay in the right spirit for the readers. Besides, Han and Chewie rock."

The frozen White Castles went into the microwave at once, while the oven warmed up a Red Baron four cheese. "This is going to be more calories than I get in a week," Samantha said. "Not that I'd dream of complaining."

The microwave pinged and Amy pulled out the plate of sliders. They huddled over the cold beer and warm Castles, going through both faster than they had intended to. They had become friends almost the instant that the Board chose Samantha (Amy wasn't supposed to meet candidates before the choice was made), sharing a morbid sense of humor and the sort of attitude that well-meaning teachers had always taken them aside to talk about.

They balanced each other somehow. Amy drew dead and pickled things with frightening precision. Sam wrote sweet, sentimental stories of very young childhood, which everyone recognized as well done and no one wanted to publish.

The last few months had been the same; a steady drizzle of rejection slips because her work "lacked something." Sam made a face. "Wish I knew what I lacked. Okay, so I've got no plot, but neither does Goodnight, Moon. I write about really trivial childhood stuff but so does Beverly Cleary. And I really exaggerate stuff and get really silly, but, well, all I can say is, Shel Silverstein, Calvin and Hobbes, Maurice Sendak, The Phantom Tollbooth. And of course, Little Amy. Which I hope you'll forgive me for saying."

"I live to be said. I don't know. Dad broke his heart and bank account for most of his life, and two different editors laid their jobs on the line to keep the series going, and about fifty librarians and book sales people created a fan club that could never get up to a hundred members—and then one day, presto, he does a lightning re-write of A Midsummer Night's Dream, Titania strikes back with the genders reversed, Little Amy as the Counter-Puck, and making fun of my first boyfriend by setting him up as Bottom, and zip, bop, bang, he's richer than God."

"I've told you before I started reading those books long before Amy and Titania. I got Amy and the Secret Cave for Christmas right after it came out because I was already such a big Little Amy fan. Thanks for the food but please don't insist that I crap all over the only good thing in my childhood."

"Sorry. I really do hope whatever made Amy and Titania a success wallops you next week."

"Can you stand one question? I really don't want to be nosy—well, I do want to be nosy, but I don't want to offend you."

"If you do I'll just break a plate over your head and get over it."

"Great. Uh, you just said your father was making fun of your first boyfriend in that book—did you hate him for that?"

"Hate him? I don't even remember him. His name started with W—Walt? Wally? something like that—and Dad said, very accurately, that he was the sort of person you wanted to look at until you heard, the kind that the phrase 'beautiful but dumb' was coined for, and I was crazy about him then, I guess, but I'd probably have to reread the book. What are you laughing at?"

"Oh, you really don't remember Amy and Titania."

"I said I don't."

"Well, he was beautiful and dumb and that was funny, but the idea of him being named Wally, it's just—just so—I mean—"

Once Samantha got going on the wonderfulness of Dad's books, she could go for hours without ever producing an independent clause, giggling and waving her hands into a string of happy "you knows." Amy did her best to look stern. "Come on, take care of yourself, Sam. Make sure you consume enough of all this lovely fat, carbs, and alcohol. You need it a lot more than I do."

"Doing my best. There's only so much of me to go around it." She folded up a drippy piece of pizza and ate it like a sandwich. "Funny thing, for a lot of us, Amy and Titania kind of spoiled things. We liked it, but not as much as the earlier ones, and suddenly Little Amy wasn't an inside joke for sad lonely brainos. But it's good that after all that work, your dad got something out of it. That's a good thing, surely?"

"Yeah. He did work hard for what he got."

They decided the first frozen pizza and round of beers would be lonesome without another, and dealt with those in pleasant silence before Samantha finally said, "Um, not that it's necessarily my place to bring up the subject, but what did you have in mind for the sleeping arrangement?"

"Well, ownership has a few privileges attached. I'm taking the bed. Can you be comfortable on the nap couch in Dad's office?"

"I sleep there half the time anyway. I was going to suggest it."

They got blankets and a fresh pillowcase for the nap couch pillow from one of the cedar chests in Amy's room. As Amy turned the light off in the office, she couldn't help feeling that she really ought to have tucked Samantha in. "Good night, Sam."

"'Night," the voice under the covers muttered. "Thanks for not bein'ad."

Mad? Sad? Bad? Probably mad.

Amy hesitated a moment in the doorway. The big, high triangular window—one of Dad's few really successful building projects—framed Taurus's head, with the Pleiades in the upper right corner and just the tip of Orion's bow in the bottom point. She had seen the same stars framing Dad, slumped asleep over his desk.

She closed the door very softly.

Back in her room, she unpacked her duffel, and there was her stupid soul again, still a lifeless gray rag, with that remarkable drawing on it. She spread it out on her bedspread to look at it a bit more, positioning it carefully—the diamond that enclosed the gaudy Valentine heart on the bedspread was the same shape and size as—

Though the lights were on, the floor was dark as it rushed up into her face.

"Come on." A hand was shaking her shoulder, in an annoyingly tentative way. She rolled over on her back, and it was Wolfbriar looking down at her, exactly as he had been when she had been thirteen and he had been whatever age an elf ever is; they are all perpetually newborn, which is the only way they can bear living forever, and they never die, which is the only thing that makes their intense sensory memory endurable. "Come on. Wake up."

"What happened?"

"Your soul became not-in-pieces."

"Whole," Amy said, sitting up and rubbing her head. She'd had hangovers she liked better than this. "Whole," she repeated. Elves were like that with human languages; they would usually only learn one of any pair of antonyms.

"Whole," he said. "Your soul has been not-whole for a not-brief time."

Or then again, who really understood elves?

"Yes, it has. Since . . . oh, my. Since the night in here." Her eyes widened. "We hid you in the trunk because my dad was coming upstairs yelling 'Who is up there with you?' . . ."

Now she remembered the kissing and touching that had gotten more and more exciting; the final wild moments where she had whispered "yes, yes, yes . . ."

The never-before-tested bed creaking and squealing in rhythm, betraying them but she hadn't cared—

Then "What the hell are you doing up there? Is Wolfbriar up there with you?" in a drunken bellow from the front room, and the realization that Dad's little pixie must already have gone home, and the thumps of a big man hurrying up a ladder . . . Wolfbriar hiding in the cedar trunk, willing himself to not-be.

But since he would not exist to terminate the hiding spell, he had had to set a condition. And with Amy's soul newly divided, surely it must have seemed to him that she would repair her soul as soon as possible, so he had made her soul's reunion the trigger for his reappearance, but . . . well, sometimes you just don't get around to things, she thought.

She stood up, breathing deeply, and now her vision had cleared and become double again, the way it naturally was for a half-elf. She saw The Cabin as she had known it as Little Amy, and she saw the clumsily modified prefab house by the borrow pit. Her elf-eye delighted in the weave of silver in the walls, and her human eye saw the rough-fitted, stained and urethaned but never sanded enough number two pine of the floor, and—

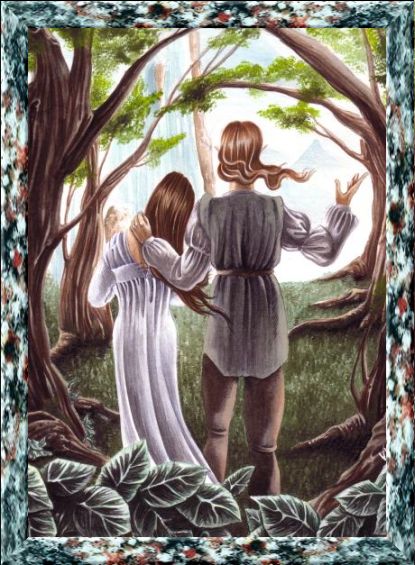

She saw the bridge to her window, that Wolfbriar had sung into existence so long ago. He reached for her hand.

"Let's go," he said, tugging at her hand. If they walked down that bridge together, it would complete what had been begun; she would be off to Wyoming with him, like Ami on her pegason.

"You're in a hurry," she said.

"You would be too, if you'd been not-out of a trunk for thirteen years," he said, and they both began to laugh.

"My friend is asleep in the other room," Amy said. "But if we're quiet, we can go down to the kitchen and talk—"

"Food, yes, and water, and . . . um—"

"Next door down the hall," Amy said. "Then just come downstairs. You have been in a trunk for thirteen years, haven't you?"

When Wolfbriar came down to the kitchen there was another bout of figuring things out, because he couldn't touch iron and all of the tableware was stainless steel, but eventually she made a pile of sandwiches for him. "I sought," Wolfbriar said, "to carry off a Singer-of-the-True's daughter. That would have been a not-small not-failure for me to claim, in Elfland, where I have long been thought not-ugly but not-impressive. The deed would have been not-small enough to make not-commoners of us both."

Amy shrugged. "At the time you came, I was very carryoffable. But now I've lived on this side for another thirteen years, and I'm human down to the bone, and, well, it's just different."

"I know," Wolfbriar said sadly. "The ceranin is gone from your soul. I thought the only chance was to lead you over the bridge, right then, and off to Elfland, because I knew your soul would hold you back."

The ceranin?

That gaudy pattern, Amy realized. That picture of all the magic her heart was capable of and of what it might be on the other side—

She ran up the stairs to look. The bedspread was now all gray muslin, but on it was the most amazing layout; in the blue chalk, the same perfect lines depicted every organ of the human body with photographic precision but the clarity that only a line drawing can have. It wasn't gaudy at all; this spoke of precision and of things as they were. She loved it at once.

The bridgehead was at the window, and the long bridge descended across the pool, Little Amy's pool, composed as a mirror in the light of the rising moon; there was the falls, and there the flat rock where the Ute ghosts danced, and there . . .

She let herself see with her other eyes, and there was the frozen spill from the culvert, and the old borrow pit gradually silting up to become the meadow it had been before, and it was just another redneck homestead in the Rockies. Barely perceptible with her human eyes, the bridge glinted as if outlined in faintly glowing spiderwebs.

The gravel along the shore would crunch and there would be no diamonds in it. The borrow pit had some carp and the occasional whitefish, just garbage fish really, and would be deep green in the summer because of the mud that ran into it and because it was warm and shallow. Amy had smoked her first (and last ever, it was nasty) cigarette over there, sitting with Dennis; she had caught some big gross carp and fed them to Rags, her old buddy of a tomcat; she had thrown rocks at the water out of sheer boredom, and gathered jars of pond water and sat for hours at the microscope, one eye on the eyepiece and the other gazing at her drawing.

She had spent one whole summer of her science project, out there with her snorkel, collecting water at one foot intervals to see how the microbial life changed from top to bottom.

The first human boy she had kissed had been the one that she shot floating bottles with. Dad would save her a case of beer bottles and they'd toss them out in the water and plink until the bottle erupted in a shower of glass shards and went to the bottom, and one day when they'd sunk a bottle after far too many tries, he had carefully set down his pistol, and then hers, muzzles pointed away (they had both had the NRA class), and put his mouth on hers.

"The lakes of Elfland," Wolfbriar said, "do not need glamour to be beautiful. There are no borrow pits in Elfland any more."

She had been to Elfland; as a Singer-of-the-True Dad had been invited, and had taken her. Every pond there sparkled like a jewel, but it had no hydras, no paramecia, just sapphire-clear water. After sneaking out at night, she had sat in the moonlight with Wolfbriar and the glamour had crawled up around them till it was as beautiful—and as untouchable—as a movie of a smiling face projected onto a cloud. She had walked along the walls of the reconstructed town of Casper, and marveled at the smooth perfection of ivory and mother of pearl that went on for miles, and never once seen graffiti, or a water stain.

"Do you know what happened at the end of every one of Dad's books?"

"No," Wolfbriar said. He was standing very close.

She pushed him away. "Little Amy came back to the real world, happy to have been away, but glad to be home."

"Oh," a little voice said.

Amy turned. Samantha was staring at them. "I heard voices and, um—"

"It's all right. Turn on the light, will you? Wolfbriar's glamour is getting to you because of the moonlight."

Samantha reached for the switch and flipped it.

"You're even more beautiful without the glamour," she told Wolfbriar. "I've never met one of your kind before."

Amy suddenly whooped, the reaction and the thought hitting so fast that she wasn't aware that she was reacting until she already had. "Oh, my. Oh, my. Well, it's a petty nasty mean pleasure, but I'm not skipping it for anything. I get to quote Tolkien in Dad's house! 'Yes, Sam, that's an elf!'"

Wolfbriar was staring back at Sam. "You are a Singer-of-the-True."

"Unpublished."

"It does not matter who listens, only who sings. You are a Singer-of-the-True."

"Well, I guess I like to think so."

Amy looked at the clock. Three in the morning. She looked back and from the way Samantha and Wolfbriar were walking toward each other, she realized that the magic that gathered around The Cabin—oh, she'd always known Dad was writing about a reality—had managed everything perfectly. "Why don't you two head down the hall," she said, "and in the morning we'll all catch up. I think you'll find you have a lot to talk about, but I'm all talked out and really sleepy."

They went out holding hands, and she climbed the stairs and slipped into bed, yet again. As she fell asleep, she could see the stars very clearly, and the bridge just barely, and the blue chalk glowed on her bedspread and she realized she might work all her life to be able to draw, just once, as well as what was already on her soul. Tomorrow, perhaps, she would put it in a chest to keep it nice, and then think about how best to take it along home with her, but for tonight, just once more, she wanted to be warmed under it.

As she had figured would happen, just before dawn, they came tiptoeing through, holding hands, as if they had been holding hands for three hours. "Don't go without saying goodbye," she said, rolling out of bed.

Samantha and Wolfbriar permitted her to hug them both, and Samantha said, "I left you a note. Three CDs of finished work and a short letter to mail to my agent. And a box of my personal stuff to send UPS to Coeur d'Alene; across the border it usually takes a couple of weeks but Wolfbriar promises me they'll have everything I need. I left most of my money to cover your trouble and the postage and all. I'll try to write to you but you know how it usually goes."

She watched them walk across the bridge, or float on air above the borrow pit, and eventually they reached the other side. They stepped off the bridge and turned and waved. A big sturdy pegason descended from the swarm of morning stars, and they were off. She waved until the bright white pegason was just another star, moving slowly as a satellite. Then she went back to bed and slept till noon.

After getting a burger at the grill downtown, she put her now-complete soul into her duffel; she realized she could leave behind the elf-clothes, which were floppy and baggy and uniformly gray-ugly. There was a Victoria's Secret in Boulder, or maybe she'd just go a bit further, down to Flatirons Crossing Mall, hit the major department stores and the trendy-girly stores and so on, spend some of that big pile of Dad's money that had been building up for so long. She'd need makeup, and perhaps to find a hairdresser who wouldn't snicker, and . . . well, today was going to be expensive but fun.

She looked at the clock. Even if he had decided to sleep in, Derrick would surely be up by now.

He sounded very pleased to hear from her.

"Just me," she said. "Plain old goddam Amy. You know my Dad used to call me that? He had a pet name for me, the abbreviation for plain old goddam Amy, Poga. No, actually, it sounds terrible, but I'd kind of like it if you'd call me that. We can talk about it when you get here. Now pack a bag, and get up here this evening, but don't be too early—shall we say eightish?" She gave him directions and made him read them back.

"Plan to stay tonight and Sunday night, okay?"

"All right," he said.

"You sound funny."

"Stunned. Very happy, but I'm stunned, Amy."

"Amy?"

"Okay, I'm stunned, Poga."

"I like the way you say 'Poga,' Derrick, it's sweet." She stretched luxuriously, cradling the phone against her ear and neck, rubbing where she planned to have Derrick do a lot of kissing. There was no one there to appreciate it but she tumbled her hair around with her hand in a way she knew made her look cute, exposing one pointed ear. Ditch the brown contacts and show the gold eyes, human guys liked that. Haircut, new clothes, girly shoes, come'n'get it undies, the whole froufy nine yards. Like she hadn't done since high school. "And do not show up early. It takes me a while to turn into plain old goddam Amy. But we're both gonna like her."

John Barnes is the author of many novels and short stories.